|

|

Iraq’s Provincial Elections and their National Implications

On April 20th, Iraq will hold its third provincial elections since 2005. There are 447 open seats nationwide, and competition for them is fierce. Previous elections illustrate that winning provincial seats can reverberate on the national level. A simple majority of seats offers the parties an opportunity to control the senior provincial posts, including the governorship and chairmanship of the councils. Control of these positions provides space for maneuvering to achieve national level objectives. In the aftermath of 2009 provincial elections, Prime Minister Nouri Al-Maliki’s State of Law Alliance (SLA) was able to win a majority of seats.[1] Maliki used his control of the governorship in Maysan province to help secure a second term by offering that province’s governorship to Muqtada Al-Sadr’s movement in exchange for the Sadrists’ backing of his premiership.[2] Furthermore, the 2009 provincial elections produced players who were later able to translate local success onto the national stage. This includes the current parliamentary speaker, Osama Al-Nujaifi, who along with his brother Atheel Al-Nujaifi, the current governor of Ninewa, emerged on the national stage after their coalition performed well in Ninewa’s 2009 provincial elections.[3]

Magnifying the significance of the elections in 2013 is the fact that they are the first to be held since the withdrawal of U.S. forces in December 2011. Iraq enters these elections at a decisive moment. Unlike 2009, Maliki has now firmly consolidated his power in the face of a weak and divided opposition. The Iraqi Sunnis feel marginalized by the Baghdad government and have resorted to protests to express their dissatisfaction. The Iraqi Kurds feel threatened by Maliki and his policies and have decided to consolidate relations with Turkey to counter Baghdad’s policies. For the Iraqi Shi‘a, Maliki’s dominance in state institutions signals to them that he is not interested in power-sharing, but rather in establishing himself as the leader of the Iraqi Shi‘a community. Provincial election outcomes will signal to Maliki how aggressively he can pursue his majoritarian objective. Washington and the international community should pay close attention to these elections and their aftermath.

Functions of the Provincial Councils

Iraqi provincial councils are designed to function like state assemblies in the United States. According to the Law of Governorates not Organized into a Region, they are defined as “the highest legislative and monitoring authority within the administrative boundaries of the province that have the right to issue provincial legislations that enable them to administer their affairs in accordance with the principle of administrative decentralization that does not violate the constitution and federal law.”[4] The specific prerogatives of the councils include:

- Electing the provincial governor and his deputy, questioning them, and relieving them by an absolute majority of the votes on the council.

- The right to request turning the province into a federal region with one-third of the votes of the provincial council members.[5]

- Certifying the nomination and removal of senior posts at the director-general level in the provinces. Candidates need to receive an absolute majority of votes in the council.

- Approving security plans presented by the province’s security authorities.

- Dissolving the council by a majority vote and upon a request by one-third of local voters. The national Council of Representatives (CoR) also has the authority to dissolve provincial councils with its own absolute majority upon a request by the governor or one-third of the members on the council.

Iraqi provincial councils serve a 4-year term, and each council has 25 seats in addition to one seat for every 200,000 residents in the province. Based on population, Baghdad has the highest number of seats with 58, and Muthanna has the lowest number with 26.[6]

Although elected locally, the councils still fall under the authority of the national Council of Representatives. The CoR has, by and large, been supportive of the provincial councils, including holding conferences to discuss and urge the enhancement of their authorities in coordination with the federal government.[7] This has especially been the case since the election of Osama al-Nujaifi as speaker of the CoR in November 2010. Al-Nujaifi is a rival to Maliki and has sought to establish himself as a legislative counterweight to Maliki’s executive authorities. Nujaifi’s objective in supporting the provincial councils has been to help decentralize power to the provinces in order to offset Maliki’s centralizing tendencies. For Nujaifi, the more powerful the councils, the more difficult it becomes for Maliki to pursue centralization policies. Nujaifi’s ambition has not been fulfilled, however. On the contrary, Maliki has been able to resist the legal authorities of the councils. For example, he delayed the procedures of forming a region as requested by Diyala and Salah ad-Din in November 2011.[8] Practically, the CoR has not interfered greatly in the work of the councils.

Despite the legal powers given to the councils, provincial authorities complain that the federal government appoints local officials without consideration for provincial authorities and that federal ministries often delay funding requests for local projects.[9] Provincial governments are still dependent on budgets allocated by the federal government, and this fact places a great deal of power in the hands of the central government. Overall, councils complain that they have not been able to exercise their powers freely in the last four years. To be sure, however, the provincial councils can also be blamed for being inefficient and ineffective in governance.[10]

Comparison to 2009 Elections

The Independent High Electoral Commission (IHEC) which is responsible for organizing and executing elections announced that there are a total of 265 political entities competing in the April 2013 elections. IHEC defines an entity as a certified political party or individual candidate. Eighty-five of the 265 entities are “renewed,” which means they competed in previous elections, while the one hundred and eighty new entities did not. In the 2009 elections, there were a total of 427 entities, with 344 new and 83 renewed. The reduction in the total number of entities competing from 2009 to 2013 is due to a decrease in the number of new entities, which indicates that political parties are consolidating. Some entities have decided to form coalitions, and as a result there are 50 political coalitions in 2013. In comparison, there were 38 coalitions in the 2009 elections.[11]

The chart below illustrates these comparisons between provincial elections in 2009 and 2013:

The larger number of coalitions is significant because it further demonstrates that parties sense the advantages in forming coalitions for competitive purposes. This is particularly the case for smaller parties that seek an edge by allying with major coalitions. In the end, though, the quality of provincial candidates matters a great deal. Additionally, the fact that there are over 80 renewed entities in both elections indicates that that there are over 80 viable parties that can sustain participation across multiple elections. Finally, there were 125 individual candidates in 2009, while in 2013 there are 29 individual candidates. The decrease in individual candidates is notable as it illustrates the challenges they face in taking on the better-funded and better-established political parties. It is worth noting that not every entity is part of a coalition, and not every individual candidate is running under a party. Iraqi voters can choose to vote for individual candidates, or for parties or coalitions.

The total number of candidates competing in 2013 is over 8,138 while there were more than 14,000 candidates in 2009. [12] As for the number of seats, there were 440 nationwide seats in 2009 while there are 447 seats in 2013. Almost seventeen million Iraqis are eligible to vote in 2013 compared to fifteen million in the 2009 elections.[13]

The Competition

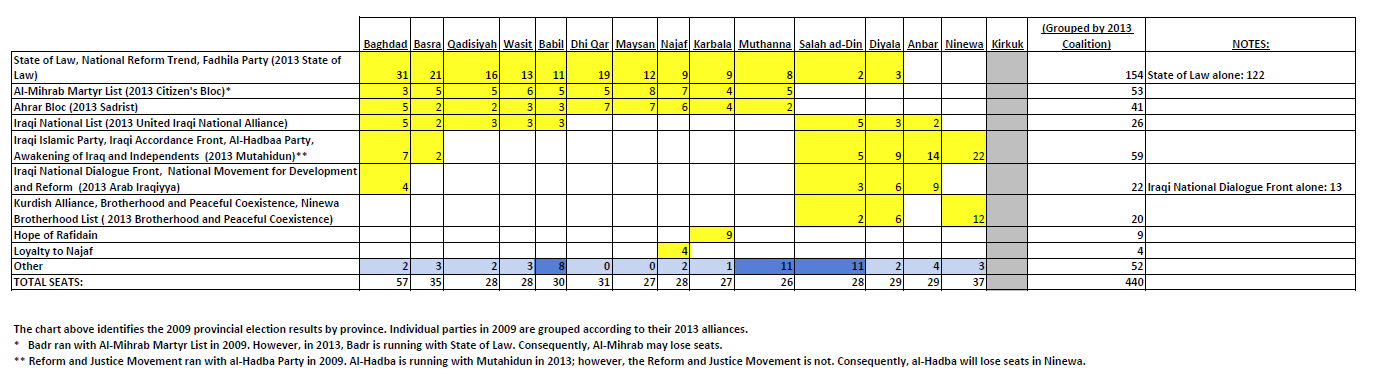

There are 7 major political coalitions to watch in the 2013 provincial elections that stand a strong chance of gaining seats: the State of Law Alliance (SLA), the Sadrists, the Citizen Alliance, Mutahidun (The United), Arab Iraqiyya, the Unified National Iraqi Alliance, and the Coexistence and Brotherhood Alliance List. The chart below shows election results from 2009, and their respective coalitions in 2013 (click to expand).

The Iraqi Shi‘a:

The State of Law Alliance (SLA): The State of Law Alliance is led by Prime Minister Nouri Al-Maliki and includes 20 groups. It is predominantly Iraqi Shi‘a and is competing as a separate coalition in 10 provinces: Baghdad, Babil, Basra, Dhi Qar, Karbala, Qadisiyah, Najaf, Muthanna, Maysan, and Wasit. The SLA made a strong showing in these provinces in 2009. It won 20 seats in Basra, 8 seats in Maysan, 13 seats in Dhi Qar, 5 in Muthanna, 11 in Qadisiyah, 7 in Najaf, 13 in Wasit, 9 in Karbala, 8 in Babil, and 28 in Baghdad.[14] These results allowed the SLA to secure senior positions in all these provinces. In Diyala and Salah ad-Din, they had a weaker showing, getting just 2 seats in each province. Just as in 2009, the SLA is competing against other Iraqi Shi‘a political parties in the southern parts of Iraq and Baghdad, where there are 315 seats up for grabs out of the 447 nation-wide. For provinces where the Iraqi Shi‘a are not a majority, the SLA has decided to align with other Iraqi Shi‘a parties in 2013. Thus, SLA member groups have decided to join the Diyala National Coalition in Diyala province, the National Coalition in Salah ad-Din, and the Ninewa National Coalition in Ninewa.

The Sadrists: The Sadrists are supporting four political blocs in the elections: The Ahrar bloc, which is running in 10 provinces; the National Partnership Gathering lead by Mohanad Mahdi Gomar Jazi, which is running in 5 provinces; the Independent National Elites Trend headed by Khdhier Abbas Hassan Salman, which is only running in Baghdad, and the State of the Citizenry bloc headed by Adnan Mohammed Taher Jassim, which is also only running in Baghdad.[15] All of these groups have shown allegiance to Muqtada Al-Sadr’s movement.[16] The Sadrists currently hold 41 provincial council seats in the councils of Baghdad and southern Iraq.[17] Like the SLA, the Sadrists have joined with other Iraqi Shi‘a groups in Diyala, Salah ad-Din, and Ninewa.

The Citizen’s Alliance: This alliance contains 21 groups and is led by Ammar Al-Hakim, who is the leader of the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI).[18] Like the SLA, the alliance has a strongly Iraqi Shi‘a Islamist character. It is competing in 10 provinces against the other Iraqi Shi‘a groups while also joining in Shi‘a coalitions in Diyala, Salah ad-Din, and Ninewa. ISCI was the dominant Iraqi Shi‘a political group after 2003. Its fortunes, however, shifted as its close ties to the Iranian government were not viewed positively by the Iraqi public. Nonetheless, it has tried to rebrand itself after the death of its former leader, Ammar’s father Abed Al-Aziz Al-Hakim, in 2009. ISCI won about 10 seats in the 2010 parliamentary elections, and its approach to these provincial elections is part of a trend to revive its base. To that end, it has chosen the slogan “My province first.” In the 2009 elections, ISCI was able to capture 53 seats between Baghdad and the southern parts of the country.[19]

Asa’ib Ahl Al-Haq (AAH): One of the Sadrist rivals, the Movement of Ahl Al-Haq (AAH), is formally not participating in the elections and will only support them by encouraging its members to vote.[20] AAH’s lack of official participation is possibly due to its desire to continue their rebranding effort into a political movement and establish a viable provincial presence. While it has been vigorously engaged in rebranding itself since the withdrawal of U.S. forces, it does not seem confident that it can compete with the Sadrists on an electoral level and would rather avoid electoral embarrassment at this point. [21]

Nonetheless, a new party named the National Al-Amal (Hope) Party was formed in November 2011 that claimed to “enjoy a good relation with AAH … and it will work to find commonalities with it.” [22] The party’s secretary general, Jassim Al-Sa‘adi is a former prominent member of AAH and was in charge of its cultural activities in the past.[23] The party has offices in Baghdad and Muthanna and has fielded candidates under Maliki’s SLA in both provinces. Al-Amal has been supportive of Maliki’s stances on federalism and the Syrian uprising.[24] The party has denied it emanated from Da’wa or AAH, but expressed its respect and appreciation for AAH’s role in “expelling the occupier from Iraq.”[25]

Al-Sadr was asked about the Amal Party recruitment effort in Baghdad in November 2011. He responded by warning his followers not to join the party. He described the group as “a splinter … from Masa’ib Ahl Al-Haq [the Plights of the Righteous], or they claim to have splintered from [AAH] in order to enter elections and kill the innocent through politics.”[26] Sadr often uses “the Plights of the Righteous” as a derogatory play on the name of AAH.

Muthanna’s electoral politics might be one reason why Al-Amal has chosen to compete there. There was no clear winner in the 2009 elections, and the SLA and ISCI each gained 5 seats. If Al-Amal is able to win one seat, it might present AAH’s first official entry into politics and run directly contrary to Sadrist interests. Maliki has been a strong supporter of AAH’s inclusion in the political process. In addition to using AAH’s military presence to weaken the Sadrists, working with any AAH-affiliated group will represent an electoral blow to his Sadrist rivals.[27]

The 315 seats in southern Iraq and Baghdad are the prize for the Iraqi Shi‘a parties. The Shi‘a population is concentrated in the south, and this is a high total number of seats. Also, given the opportunity to control local resources, the parties are attempting to test their own popularity and ensure that they can direct the affairs of the provinces without having to work in a partnership. Maliki will use these provincial elections to measure the appeal of his desire to push for a Maliki-dominated government after the national 2014 elections.

The Sadrist strategy stands out among the Iraqi Shi‘a parties. Instead of running in one group, they have chosen officially to support four groups. This may have been done in order to accommodate the various groups within the Sadrist movement that resulted after Sadr’s decision to freeze the activities of the Mahdi Army. After that, he decided to form the Momihdun, the Monasrun, and the Promised Day Brigade (PDB), which included elite units of the Mahdi Army.[28] Another possible explanation for the Sadrist strategy is to target a new constituency within the Iraqi Shi‘a community. The name “Independent National Elites Trend” reflects their desire to attract a more educated electorate as opposed to the typical Sadrist base, which has thus far been the working-class. The specific location where the Independent National Elites Trend is competing may be another indication that this is the goal, since it is only competing in the urban and more-educated Baghdad.

It remains to be seen if this electoral strategy will be as successful as the one they followed in 2010 where they gained less votes than their competitors but were able to gain more seats due to the strategic guidance to their base to vote for specific individuals.

The Sadrists and Maliki are vying for dominance, but ISCI and its ambitions should not be ignored. In December 2011, ISCI formed the Knights of Hope Gathering as a youth organization that can mobilize as a counterweight to the Badr organization, which has since split from ISCI and has been allied with Maliki.[29] The possibility that coalition-building will be important after the elections makes any results ISCI attains crucial in the reestablishment of ISCI as a relevant force.

The picture is different for the Iraqi Shi‘a parties in the rest of the country. In Diyala, Salah ad-Din, and Ninewa, they have decided to run on the same coalition. While this is a show of unity among the parties, it also signals the ethno-sectarian nature of the decision. The parties that are fiercely competing against each other view communal Iraqi Shi‘a participation as important, and hence the united front in those provinces. This dynamic has created strange bedfellows. Although the Sadrists view Maliki with suspicion and have taken steps to challenge his authority, they are competing jointly with him against their non-Iraqi Shi‘a rivals in Diyala, Ninewa, and Salah ad-Din.[30]

The Iraqi Sunnis:

A number of coalitions are vying for the Iraqi Sunni vote:

Mutahidun (The United): Announced in December of 2012, the coalition has ten groups and is led by Speaker of Parliament, Osama Al-Nujaifi.[31] It additionally encompasses the major Iraq Sunni blocs, such as the Ninewa-based Hadba list, the bloc of former Awakening Movement leader Ahmed Abu Risha, the “Future” bloc of former Finance Minister Rafia Al-Issawi, the Iraqi Islamic Party, and the Iraqi Turkmen Front (ITF).[32] The coalition is competing in Ninewa, Salah ad-Din, Baghdad, Anbar, and Basra as a separate coalition, while it has joined forces with other coalitions in Diyala and Babil.[33] In those two provinces, parts of Mutahidun, particularly Nujaifi’s Iraqiyun party, is competing as a part of the coalitions Iraqiyat Diyala and Iraqiyat Babil. Maliki-allied Iraqi Sunni rivals accuse Mutahidun of reflecting the Muslim Brotherhood orientation in Iraq, insinuating outside ties.[34] Parties affiliated with Mutahidun won 42 seats in the 2009 elections.

Arab Iraqiyya: The coalition is led by Deputy Prime Minister Saleh Al-Mutlaq.[35] It is competing on its own in Anbar and Baghdad, with the Loyalty to Ninewa bloc in Ninewa, with Arab Iraqiyya in Baghdad, with Iraqiyat Diyala in Diyala, and with Iraqiyat Babil in Babil. It also has in its ranks Jamal Al-Karbouli from al-Hal (Solution Movement). Arab Iraqiyya is competing separately from the larger Iraqiyya coalition, which had competed in the 2010 elections.

The Iraqi Sunni political groups have followed the same pattern as the Iraqi Shi‘a parties. Nujaifi and Mutlaq have publicly attacked each other’s positions, while simultaneously joining forces under the same coalitions in Diyala and Babil.[36] Both groups competed jointly in the March 2010 elections, but fissures have appeared since then, and fractures have occurred within Iraqiyya.[37]

At the moment, Mutlaq seeks to establish himself as a major representative of the Iraqi Sunni community. He has been working with Maliki to achieve that objective, ending his boycott of the cabinet.[38] On April 7, Mutlaq personally announced a cabinet decision to allow many former members of the Ba‘ath party into the government, as well as other steps that are seen as favorable to Iraqi Sunnis.[39] By giving him the platform to announce the decision, Maliki is working to turn Mutlaq into a leader and ally who is credible in the eyes of the Iraqi Sunnis. Nujaifi, on the other hand, has been a vocal critic of Maliki and has been supportive of the anti-government protests that started in December of 2012.[40] Nujaifi and Issawi’s support of the protests may position them to gain popular support. Mutlaq’s strategy, on the other hand, is a gamble because his Iraqi Sunni base does not view Maliki favorably and might electorally punish him for the rapprochement with Maliki. In essence, these elections will start to crystallize the future of Iraqi Sunni political leadership and reveal which participation strategies may pay dividends.

The Nonsectarian Group:

The major nonsectarian group competing in the elections is the Unified National Iraqi Alliance[41]. The alliance is led by former Prime Minister and leader of Iraqiyya, Ayad Allawi. It is the only major entity competing across all provinces. This also occured in 2009 where the Allawi-lead National Iraqi List won 26 seats. The alliance retains a secular character. For Allawi, the elections are a make or break moment. He has to overcome the challenges created by the defections from his party, Wifaq, and the Iraqiyya coalition since late 2010. His 2009 performance gave him momentum to establish Iraqiyya and compete in the 2010 national elections when it won more seats than Maliki’s coalition.[42] The question now remains over whether he can repeat the same performance after the loss of a considerable amount of political influence.

The Iraqi Kurds:

Iraqi Kurds are competing under the coalition called The Coexistence and Brotherhood Alliance List.[43] The list includes the 8 major Iraqi Kurdish parties including the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), and the Gorran (Change) movement. The list is competing in Ninewa, Salah ad-Din, and Diyala, which has a high concentration of Iraqi Kurds. In 2009, the Iraqi Kurdish parties won 20 seats in Ninewa, Salah ad-Din, and Diyala.

The nature of these alliances is the product of political realities, personal ambitions, and electoral necessities. The salient conclusion remains, however, that after 10 years and 4 elections, there has not been a party that is able to compete nationwide and attract voters from different constituencies. Instead, the political parties look at the map of Iraq with its clear ethno-sectarian geographic distribution and decide to campaign and devote resources to voters who they believe will vote for them because they are from the same background. To be sure, groups like Ayad Allawi’s alliance and the People’s Will Alliance headed by Iraqi democracy advocate Ghassan Al-Atiyyah are seeking to break that dynamic by forming their cross-sectarian blocs.[44] But previous elections demonstrated that they are not universally attractive to voters.

Local Players

The 2009 elections demonstrated a number of surprising winners who are worth watching as the outcome of the 2013 elections unfolds. For example, retired General Yousef Al-Habubi ran in Karbala independently in 2009 and won 37,847 votes, making him the highest vote-getter in the province.[45] Despite that impressive showing, the seat allocation system only secured him one seat – which cannot out-vote coalitions with multiple seats. Al-Habubi has assembled a coalition this time, and will field 30 candidates.[46]

Another example of local groups that can deliver surprising performances is the Karbala-based Hope of Rafidain coalition, which won 9 seats out of 27 and allied itself with Maliki’s SLA after the 2009 elections. This allowed both groups to control the major posts of governor and provincial council chair. The same modus operandi worked in Najaf, where its current governor, Adnan Al-Zorfi, is competing with his coalition, Loyalty to Najaf. In the last election, his list brokered a deal by using its 4 seats to form an alliance with the SLA. Al-Zorfi became governor while the SLA attained the provincial council chair.[47] The same can happen in Ninewa. The leader of the Shammar tribal confederation, Abdullah Al-Yawer, is competing with a coalition named the Unified Ninewa list. He was a major player in the 2009 elections when he ran with the Hadba list and used his tribal influence to win 11 seats out of Hadba’s 19.[48] These are examples of local figures who can dictate outcome and attract voters based on their reputation and position within the community. It will be especially important to observe local candidates who emerge as influencers within various Iraqi Sunni constituencies, given the growing divide among national Sunni politicians and the Sunni population writ large.

The Exception of Anbar, Ninewa, and Kirkuk

Provincial elections have been delayed for no more than six months in Anbar and Ninewa provinces, ostensibly on account of security concerns. These provinces have played host to the most highly concentrated elements of the anti-Maliki protest movement that began in December 2012. The delay presents an opportunity for Maliki’s Sunni allies, such as Mutlaq and Karbouli, to regroup and find ways to attract voters from among the protesters.[49] They have both been unable to capitalize on the anti-government protests for electoral gains, although the recent move on de-Ba‘athification may lend a hand to Mutlak. The delay, however, will temporarily disenfranchise the residents of those provinces. Iraqi Sunnis clearly pivoted to politics as a means to achieve their goals as illustrated by their massive turnouts in the last two elections. If the elections are not held there soon, Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) will be better-positioned to recruit and persuade the Iraqi Sunnis that violence is the only avenue to achieve their objectives in light of perceived marginalization by an Iraqi Shi‘a government. AQI has already been active in assassinating political candidates and deploying violence to discourage political participation.

Kirkuk province will not be included in the elections this time, just as it was exempted in 2009. This exception makes its provincial council the longest-serving in the country since its election in 2005. Disagreements among the provinces’ ethnic groups scuttled any effort to legislate a special law for the elections in the province. The Iraqi Turkmen, for example, insisted that elections only be held after an examination of the controversial voters’ list, to reflect the demographic change in the province since 2003.[50] This position was taken much to the chagrin of the Iraqi Kurds who were pushing for elections.[51] Similarly, some Iraqi Arab groups were supportive of holding elections in the province. This alignment was seen as a threat by the Iraqi Turkmen.

Despite not having elections, lessons about Kirkuk’s politics can be drawn. A clear crystallization of ethnic coalitions emerged in preparations for possible elections, as 17 major Iraqi Arab parties formed one list called the “Common Arab Gathering,” and 13 Iraqi Kurdish parties formed one unified list, while the Iraqi Turkmens’ most competitive representative is the Iraqi Turkmen Front. [52]

Given the disputed claims over Kirkuk, electoral alliances are expected to form along these lines. The formation of these alliances is also an indication of the lack of trust among the provinces’ political groups.

Campaigning in Iraq

Electoral Themes

The competing entities have been using a variety of platforms to reach out to voters. Campaign messages vary between national issues and local grievances; local issues include promises to address corruption, lack of services, and unemployment. Maliki addressed campaign rallies in southern Iraq where he touched on themes that warned of the return of Ba’athists and sectarian figures as a result of the elections. He may, however, be punished by Iraqi Shi‘a voters for his recent decision to amend de-Ba’athification laws. Maliki also addresses local issues and points to opened projects to signify his cabinet’s achievements for the provinces.[53] For Nujaifi, the focus is also local, but Mutahidun’s message has urged citizens to vote in order to change the treatment provinces like Diyala receive.[54] Each side is employing emotional and sectarian issues to garner support; after all, Diyala sees itself as suffering from a heavy-handed approach from Baghdad. The focus on local issues was prominent when Ammar Al-Hakim launched a tour in southern Iraq, where he kept his speeches focused on the local-level needs of each community as opposed to focusing on national and general issues. In a rally in Babil – home of many of Iraq’s archeological sites – Hakim emphasized the need to refurbish those sites and announced a specific initiative that will attend to Babil’s needs.[55]

Anti-corruption has also appeared as a theme, as Maliki’s opponents single out the $4 billion Iraqi-Russian arms deal, which was marred by corruption and resulted in the firing of the government’s former spokesperson, Ali Al-Dabbagh. They point to this debacle to demonstrate that Maliki’s SLA has not been able to address corruption.[56] The issue of corruption is a ripe tool for Maliki’s opponents to use against him, and it is likely to recur as a theme in the national elections scheduled for 2014.

Electoral Platforms

Coalitions and candidates use diverse platforms to deliver their message and reach out to voters:

- High-profile launch events and rallies: This method is especially important for the major lists with large funding. For example, the SLA held an event on March 30 at Baghdad’s Al-Rasheed Hotel in the highly-protected Green Zone.[57] During the event, Maliki forecast that his coalition will “gain a political majority in all provinces.” Other major coalitions have followed the same pattern. Holding massive political rallies at stadiums is also popular, such as ISCI’s rally in Basra on April 3.[58]

- Posters: Since the campaign officially began on March 1, streets in Iraq have been flooded with posters advertising for candidates. The strategy for many new candidates has been to show themselves alongside major personalities on the list, as a means of indicating their support or affiliation.

- Television and newspapers: The major coalitions own satellite TV stations and newspapers and they have been using them to broadcast their message. The well-established Da‘wa has been able to employ the Afaq channel for electoral purposes, while ISCI has been using its Al-Forat Channel. Other competing parties have their own channels as well, such as Al-Ghadir TV which is owned by the SLA’s Badr organization. The Iraqi Kurdish parties also have channels; the KDP controls Kurdistan TV, the PUK runs Kurdsat, and Gorran operates the Kurdish News Network.

- Social media and electronic campaigning: Candidates are using Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and their own websites to reach to voters as well. Utilizing these methods to reach voters is unique, but the impact is still not great since the majority of Iraqis get their news and information from television stations. It does show, however, an inclination by the parties to deploy any means at their disposal to amplify their message.

- Extra-electoral means: As with previous elections, the practice of distributing gifts and promises to voters by candidates is reported in these elections.[59] This practice favors the well-funded parties and those that deploy patronage networks through their control of ministries. Maliki also gains an advantage through these means. In 2008, he formed Tribal Support Councils (TSCs), which are tasked with supporting the provincial government in security-related matters. But Maliki’s opponents have been critical that he has been able to harness the support of the TSCs to spread state resources to his advantage, especially during elections.[60] The cabinet allocated over $8,500,000 in salaries for the TSCs in November 2012. IHEC regulations criminalize any attempts to buy votes and religious authorities have forbidden the phenomenon, but it remains a fairly common phenomenon.[61]

Implications

Political parties will seek to prove supremacy in their respective geographic areas. The predominantly Iraqi Shi‘a south will witness competition between Prime Minister Nouri Al-Maliki’s State of Law Alliance (SLA), and Al-Sadr-supported groups. For the Iraqi Sunni parties, Osama Al-Nujaifi and his brother Atheel Al-Nujaifi will seek to cement their position in the predominantly Iraqi Sunni areas while facing competition from Mutlaq and the Iraqi Kurds in Diyala and Ninewa. The elections will also be a test for former Prime Minister Ayad Allawi who is leading his own list for the elections.

Provincial councils possess the authority to initiate steps to convert individual provinces into federal regions. This is a useful political asset for a party that believes that it needs to carve out an administrative area of influence, or to react to perceived governmental marginalization. Use of the councils for these purposes was evident when the predominantly Sunni councils of Salah ad-Din and Diyala requested to form a federal region in late 2011.[62] Both councils made the decision in response to “marginalization and discounting and the confiscation of authorities,” according to a local official from Salah ad-Din.[63] Provinces with an Iraqi Shi‘a majority, such as Basra in 2010, have also voiced their desire to become a region.[64] Political victories on a provincial level can provide leverage even without national electoral success. It is plausible that if Maliki’s coalition kept control of the Basra provincial council, while not retaining the premiership, it could seek to announce the oil-rich Basra as a federal region as a means of maintaining its influence.

The elections will be a referendum on the performance of the provincial councils and the local officials. In 2009, the majority of council members lost their seats in a show of voter dissatisfaction.[65] Concurrently, the elections will be a test of Iraqi voters’ embrace of the political system. Voter turnout will be crucial in gauging the view of the Iraqis towards the political process. The overall turnout for the 2009 provincial elections was 51 percent, with predominately Iraqi Sunni provinces such as in Salah ad-Din and Ninewa registering higher turnout of 65 percent and 60 percent, respectively.[66]

Technically, the newly-installed IHEC will also be under the microscope. It has carried out successful electoral processes since its inception in 2007. However, the previous commission and its head, Faraj Al-Haidari, came under pressure from Maliki and the SLA, culminating in the SLA initiating an unsuccessful attempt to withdraw confidence from the commission and replace it in July 2011. Furthermore, Al-Haidari was detained in April 2012 over graft charges.[67] Deputy Prime Minister Saleh Al-Mutlaq then stated that “the arrest … indicates the presence of political targeting of the IHEC and the intention to either falsify the elections or postpone them.”[68] Al-Haidari was released shortly afterwards, but the message his arrest sent was clear: the prime minister can place pressure on the IHEC.

The first test for IHEC in these elections came on April 13 when special voting for Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) – the army and the police – took place. There are growing concerns that commanders of ISF units would pressure their subordinates to vote for a “specific side that has control over this institution [ISF]” as Osama Al-Nujafi reportedly stated in a TV interview, likely referencing Maliki’s control over the Iraq’s security forces.[69] Nujaifi’s concern was echoed by ISCI’s leader, Ammar Al-Hakim[70] and the Sadrist’s spokesperson.[71] The ISF are estimated to have over 650,000 army and police personnel according to IHEC, and their votes can be decisive.[72] IHEC appears to have carried out the special voting elections with no controversy.[73] It is imperative for IHEC to repeat the performance for the elections to be seen as free and fair.

As with any elections in a fledgling democracy, acceptance of the results will be key for a stable post-elections period. This applies to office holders and their challengers respectively. In the aftermath of the national 2010 elections, Maliki contested the results in Baghdad and demanded a recount which subsequently took place and upheld the results.[74] In 2009, Abu Risha in Anbar threatened to resort to violence after early indications (which proved to be wrong) showed his group losing.[75] No violence materialized from those events, although the presence of U.S. forces could have played a role in preventing any violence that resulted from discontent with the electoral outcome. With U.S. forces absent and an ISF whose leadership is largely partisan, the prospect of post-elections violence is worrisome. Indicators of rejection of 2013 elections have not yet begun to surface. 117 provincial candidates have been excluded from the 2013 elections, and to date, none have spawned exceptional controversy.[76] This was also the case in the 2009 elections. Excluding candidates tends to be more contentious in the context of national elections, as was seen in 2010.

Final results are scheduled to be announced on May 17, 2013.[77] If Maliki’s SLA achieves a majority in the councils, he will be emboldened to push ahead with his ambition to form majoritarian government.[78] This may also mean he will try to attract Iraqi Sunni support from Mutlaq and Karbouli to create an image of inclusiveness. Maliki’s opponents will likely try to limit his powers and any gains he achieves by forming local governments that will exclude Maliki and any groups allied with him.

Either way, the outcome and the process will carry lessons for the 2014 national elections. IHEC’s technical abilities will be tested, and its willingness to remain independent will be an opportunity to correct any mistakes before the 2014 elections. Additionally, the results of the elections can redraw Iraq’s political map. National figures like Maliki, Nujaifi, and Hakim boost their coalitions when they campaign for them. Nonetheless, the results will demonstrate if their national appeal can overcome the voters’ assessment of the local candidates representing them. Similarly, the results will show if national election themes will trump voters’ local grievances and issues.

These elections are no less important for Washington. The administration will be well-advised to monitor the elections and particularly the aftermath. It should be proactive in voicing objections to any judicial moves that might favor Maliki in case of a dispute over results. More importantly, the administration should not be seen as siding with anyone in the elections; rather, it should clearly and firmly state that every Iraqi votes counts.

[1] http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/surprises-from-iraqs-provincial-elections

[4] Law of Governorates not Organized into a Region, Iraqi Council of Representatives website, http://parliament.iq/dirrasd/law/2008/21.pdf

[5] Law for Region formation, Iraqi Council of Representatives Website,

[6] Law of Governorates not Organized into a Region, Iraqi Council of Representatives website, http://parliament.iq/dirrasd/law/2008/21.pdf

[9] http://www.iraqhurr.org/content/article/24389198.html; http://www.alsumarianews.com/ar/47228/print-article.html

[11] Independent High Electoral Commission (IHEC) results announced after January 2009 elections.

[12] IHEC figures; http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/arabic/middle_east_news/newsid_7855000/7855591.stm, http://www.dw.de/%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%AA%D8%AE%D8%A7%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%AD%D8%A7%D9%81%D8%B8%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D9%85%D9%88%D8%B9%D8%AF%D9%87%D8%A7/a-16709394

[14] IHEC figures

[15] Sadrists bloc website, http://www.pc-sader.com/index.php/%D9%85%D8%B1%D8%B4%D8%AD%D9%8A%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%AD%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%B1/index.1.html

[17] IHEC figures

[19] IHEC figures

[21] http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2013-02-18/world/37160889_1_al-haq-shiite-religious-leader-iraqi-shiite

[24] http://www.sotaliraq.com/iraq-news.php?id=32862#ixzz2Nu4JXj4K; http://alliraqnews.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=50795:2012-09-05-10-42-16&catid=41:2011-04-08-17-27-21&Itemid=86

[25]http://ar.radionawa.com/%28A%28O7ZBpTXdzAEkAAAAZGM4Njg2ZTgtMWIwZi00Nzg2LWE1ZjktNmRjZWM0OTEwNWNi3_PPEdqa6AE3sfPUEspEQxhMJgc1%29%29/Detail.aspx?id=21788&LinkID=63&AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1

[27] http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2013-02-18/world/37160889_1_al-haq-shiite-religious-leader-iraqi-shiite

[32] http://ar.aswataliraq.info/%28S%28itrd5o451n2is0urrxmb2svb%29%29/printer.aspx?id=308982; http://www.iraqiparty.com/news_item/7159/

[33]http://almustaqbalnews.net/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=2340:%D8%AA%D8%A3%D8%B3%D9%8A%D8%B3-%D8%AA%D8%AD%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%81-%E2%80%9C-%D9%85%D8%AA%D8%AD%D8%AF%D9%88%D9%86-%E2%80%9C-%D8%A8%D8%B2%D8%B9%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D8%AC%D9%8A%D9%81%D9%8A-%D9%84%D8%AE%D9%88%D8%B6-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%AA%D8%AE%D8%A7%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D9%82%D8%A8%D9%84%D8%A9&Itemid=579

[35] http://www.ikhnews.com/index.php?page=article&id=79826; http://www.almashriqnews.com/inp/view.asp?ID=34768

[40] http://www.almadapress.com/ar/news/8053/%D8%A7%D8%A6%D8%AA%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%81-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%83%D9%8A-%D9%8A%D8%AF%D8%B9%D9%88-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%AE%D9%88%D9%8A%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D8%AC%D9%8A%D9%81%D9%8A

[42] http://bit.ly/11o64S6

[45] http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/surprises-from-iraqs-provincial-elections

[46]http://ar.aswataliraq.info/%28S%28xlsakh45moyqrw55dqjr1bep%29%29/Default1.aspx?page=article_page&id=310246&l=1

[52] http://ar.aswataliraq.info/%28S%28jessliefd1av4m55ahnbwfea%29%29/Default1.aspx?page=article_page&id=309001; http://www.ikhnews.com/index.php?page=article&id=34774; http://www.alsumarianews.com/ar/1/52490/news-details-.html

[53] http://www.almadapaper.net/ar/news/443073/%D8%AC%D9%85%D9%87%D9%88%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%83%D9%8A-%D9%8A%D9%86%D8%B3%D8%AD%D8%A8-%D8%A3%D8%AB%D9%86%D8%A7%D8%A1-%D8%AE%D8%B7%D8%A7%D8%A8%D9%87-%D9%81%D9%80%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D9%85

[54] http://almadapress.com/ar/news/9189/%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D8%AC%D9%8A%D9%81%D9%8A-%D9%8A%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%AC-%D9%84%D9%82%D8%A7%D8%A6%D9%85%D8%AA%D9%87-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%AF%D9%8A%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%89-%D9%88%D9%8A%D8%A4%D9%83%D8%AF

[55] http://almadapress.com/ar/news/9832/%D8%AD%D9%85%D9%84%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AD%D9%83%D9%8A%D9%85-%D8%AA%D8%B5%D9%84-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%A8%D9%84-%D9%88%D8%B2%D8%B9%D9%8A%D9%85-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%AC%D9%84%D8%B3-%D8%A7

[56] http://www.alforatnews.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=36924:2013-04-03-12-48-45&catid=36:2013-03-27-10-35-00&Itemid=53

[57] http://www.almadapress.com/ar/news/9178/%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%83%D9%8A-%D9%8A%D8%AD%D8%B3%D9%85-%D9%86%D8%AA%D9%8A%D8%AC%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%AA%D8%AE%D8%A7%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%AA-20-%D9%86%D9%8A%D8%B3%D8%A7

[59] http://www.alarabiya.net/articles/2009/11/09/90734.html, http://pukmedia.com/AR_Direje.aspx?Jimare=5049

[60] http://www.alsumarianews.com/ar/1/52416/news-details-.html; http://www.alsumarianews.com/ar/51517/print-article.html

[65] http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/surprises-from-iraqs-provincial-elections

[66] http://www.albawaba.com/ar/%D8%A3%D8%AE%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%B1/51-%D9%86%D8%B3%D8%A8%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%B4%D8%A7%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%AA%D8%AE%D8%A7%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%82

[70] http://www.almadapress.com/ar/news/7561/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AD%D9%83%D9%8A%D9%85-%D9%8A%D8%B7%D9%84%D9%82-%D8%A7%D8%A6%D8%AA%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%81%D9%87-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%AA%D8%AE%D8%A7%D8%A8%D9%8A-%D9%88%D9%8A%D8%AD%D9%8A%D9%8A

[72] http://www.alliraqnews.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=76507:-650-&catid=41:2011-04-08-17-27-21&Itemid=86

[73] http://unami.unmissions.org/Default.aspx?tabid=2790&ctl=Details&mid=5079&ItemID=1334857&language=en-US

[75] http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/surprises-from-iraqs-provincial-elections