By Joseph Holliday

Sunni insurgents ambushed a convoy of Iraqi and Syrian troops inside Iraq on March 4, 2013, marking the clearest example of spillover from the Syrian conflict into Iraq since the beginning of the Syrian uprising in early 2011. The attack illuminates the involvement of Iraqi actors on both sides of the conflict. The ambush is indicative of broader cross-border cooperation between Sunni militant groups seeking to disrupt Assad regime security forces on both sides of the border. The attack location is just as significant as the militants involved because it sheds light on the status of Iraq-Syria border crossing points as the Assad regime and Iraqi government seek to secure overland supply routes between the two countries. With three of four border crossing points impassible due to rebel gains in Syria, the Al Walid-At Tanf border crossing will be critical for the Assad regime and the Iraqi government to secure if they hope to maintain a ground line of supply between Baghdad and Damascus.

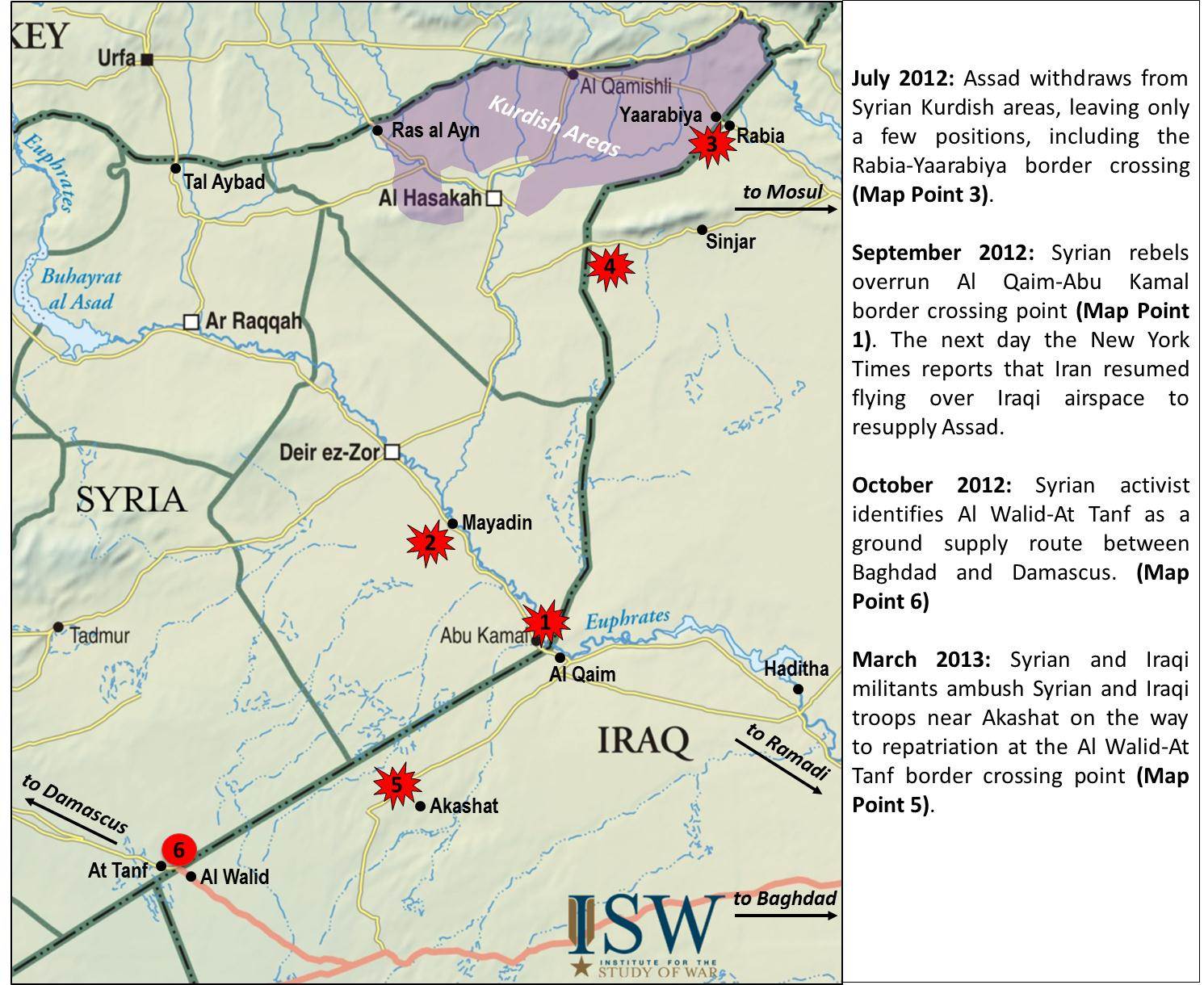

As depicted on the map, the four primary Syria-Iraq border crossing points are Yaarabiya Rabia in the north, the unofficial crossing at Sinjar, Euphrates River belt Al Qaim-Abu Kamal crossing, and the Al Walid-At Tanf border crossing near Jordan. The Sinjar route was an important crossing point for weapons and foreign fighters travelling into Iraq during the U.S. occupation. The historical strength of al-Qaeda in Iraq in the Sinjar area suggest that this route would not be useful for overland resupply to Assad due to security concerns for government forces on both sides of the border.

Developments in Syria since summer 2012 effectively closed the Yaarabiya-Rabiya and the Al Qaim-Abu Kamal border crossing points to any overland traffic supporting the Syrian regime. Assad’s forces withdrew from most Kurdish areas in northeastern Syria in July 2012, leaving these areas under the de-facto control of the Syrian Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD), an affiliate of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Assad’s troops maintained some positions in the area, including key oil and gas facilities, the Kurdish town of Qamishli and the Yaarabiya-Rabia border crossing into Iraq. However, the isolation of these facilities from the primary support zones of the Assad regime meant that Yaarabiya-Rabia could not be used as a principal overland support channel.

Syrian rebels gained control of the al Qaim-Abu Kamal border crossing point in early September 2012, reducing Assad’s Iraq-border positions along the Euphrates River belt to a small helicopter base in Hamadan (Map Point 1). By November, rebels overran the Hamadan airbase and quickly followed this victory by forcing regime troops out of Mayadin (Map Point 2). The quick series of victories allowed the rebels to claim control over the Euphrates river belt from the provincial capital of Deir ez-Zor to the Iraqi border.

Soon after Syrian rebels seized the Al Qaim-Abu Kamal border crossing in early September 2012, the New York Times reported that Iran had resumed shipping military equipment to Syria over Iraqi airspace. The timing may be coincidental, but the developments of July and September 2012 that had effectively closed two official border crossings into Syria may have presented logistical challenges to Iran’s efforts to resupply Assad overland via Iraq.

A month after the closure of Al Qaim-Abu Kamal, a Syrian opposition activist posted a map on his Twitter account depicting an overland resupply route from Baghdad to Damascus via the southern Al Walid-At Tanf border crossing point. This route travels through the middle of the Syrian Desert, away from population centers, and is the most direct route between Baghdad and Damascus. This route was geographically plausible and logical if the Iraqi government was indeed facilitating ground resupply to Assad, although no other evidence was available to corroborate the use of this border crossing point until the early March ambush.

Syrian rebels overran Assad troop positions on the Rabia-Yaarabiya border crossing point on March 2, 2013, and it later became clear that the Syrian troops fled into Iraq seeking refuge (Map Point 3). The day prior, an errant Syrian ballistic missile had landed inside Iraq near the Sinjar crossing, although the intended target remains unclear (Map Point 4). Two days after seeking refuge in Iraq, the Syrian troops were ambushed along with an escort detail of Iraqi security forces inside Iraq, killing as many as 50 Syrian and nearly a dozen Iraqi soldiers. Iraqi officials accused Jabhat Nusra and al-Qaeda in Iraq of conducting the attack (Map Point 5). This ambush illuminates the involvement of not only Sunni Iraqi militants but also the Iraqi government in the ongoing Syrian conflict.

Iraqi press immediately identified the ambush position as Akashat and later confirmed that the Syrian soldiers were on their way to repatriation at the Al Walid-At Tanf border crossing point. The Iraqi government’s attempt to repatriate these Syrian troops at the southernmost Iraq-Syria border crossing underscores the significance of the only remaining government-controlled border crossing point. This serves to corroborate the Syrian activists’ map that identifies the Al Walid-At Tanf as an overland supply route between Baghdad and Damascus.

Assad’s withdrawal from northeastern Syria, combined with rebel gains along the Euphrates River, has reduced possible overland supply routes between Baghdad and Damascus to the Al Walid-At Tanf border crossing point. The recent ambush also demonstrates the capacity and willingness of militants on the Iraqi side of the border to disrupt this route. The Iraqi and Syrian governments appear well situated to maintain control of this last overland supply route, but if this route closes, the Assad regime will have to rely on air and sea resupply routes in order to continue its campaign against the opposition in Syria.