Executive Summary:

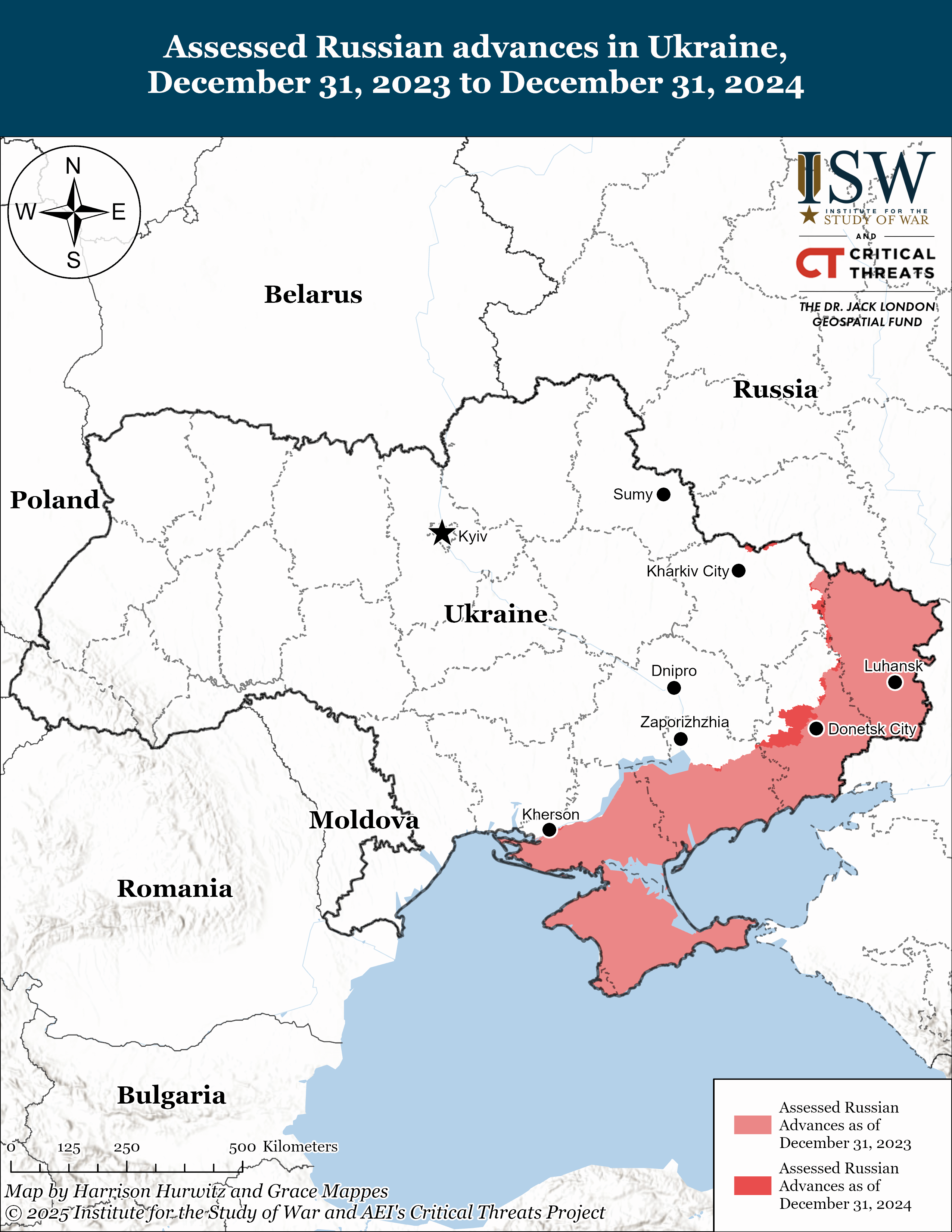

Russia dedicated staggering amounts of manpower and equipment to several major offensive efforts in Ukraine in 2024, intending to degrade Ukrainian defenses and seize the remainder of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts. These Russian efforts included major operations in the Kharkiv-Luhansk Oblast area, Avdiivka, Chasiv Yar, northern Kharkiv Oblast, Toretsk, Marinka-Kurakhove, Pokrovsk, and Vuhledar-Velyka Novosilka. Russia has achieved relatively faster gains in 2024 than throughout most of the war after the initial invasion and developed a blueprint for conducting slow, tactical envelopments to achieve these advances, but Russian forces have failed to restore the operational maneuver necessary to achieve operationally significant gains rapidly. Russia has thus paid an exorbitant price in manpower and equipment losses that Russia cannot sustain in the medium term for very limited gains.

Russian losses in massive efforts that have failed to break Ukrainian lines or even drive them back very far are exacerbating challenges that Russia will face in sustaining the war effort through 2025 and 2026, as ISW’s Christina Harward has recently reported.[1] Russia likely cannot sustain continued efforts along these lines indefinitely without a major mobilization effort that Russian President Vladimir Putin has so far refused to order. Ukraine, on the other hand, has shown its ability to fight off massive and determined Russian offensive efforts even during periods of restricted Western aid. The effective failure of these major and costly Russian offensive operations highlights the opportunities Ukraine has to inflict more serious battlefield defeats on Russia that could compel Putin to rethink his approach to the war and to negotiations if the United States and the West continue to provide essential support.

Russia’s 2024 Military Campaigns

Russian forces seized the theater-wide initiative following the culmination of the Ukrainian counteroffensive in late 2023 and held it throughout 2024. Russian forces began several offensive operations with the intent of breaking Ukraine: a renewed offensive on the Kharkiv-Luhansk axis in Winter 2023-2024 and September 2024, several efforts in eastern Ukraine, and an offensive across the international border in northern Kharkiv Oblast in May 2024. Russian forces have been conducting these operations in an effort to achieve the Kremlin’s long-held operational goal of seizing the remainder of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts by the end of 2024 and to exhaust Ukraine’s defensive capabilities.[2] Russian forces significantly increased their rate of advance, particularly in Fall-Winter 2024 when Russian forces advanced at least 1,103 square kilometers between September 1 and November 14 compared to seizing 387 square kilometers in the entirety of 2023 due to Ukrainian counteroffensives.[3] Russian forces utilized astounding numbers of personnel and equipment to achieve these gains but still failed to make operationally significant gains proportionate to the costs in combat power, resources, time, and casualties. Russian forces’ main achievements in 2024 were the seizures of Avdiivka, Selydove, Vuhledar, and Kurakhove, but no amount of Kremlin rhetoric attempting to paint these as significant victories will change the fact that these are mid-size settlements, the largest of which had a pre-war population of just over 31,000 people.[4]

The Russian military proved that it was and remains willing to sustain horrific battlefield losses for disproportionately small gains. The Kremlin sacrificed weapon systems, soldiers, and economic resources at scale to sustain its war effort in Ukraine. Ukrainian Commander-in-Chief General Oleksandr Syrskyi reported that Russian forces suffered more than 434,000 casualties in 2024, including 150,000 killed in action, and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky stated that Russian forces suffered 300,000 to 350,000 killed and 600,000 to 700,000 wounded in Ukraine since the start of the full-scale invasion in February 2022.[5] These Ukrainian numbers suggest that Russian forces suffered 41 to 48 percent of all their battlefield casualties since the start of the war in 2024 alone. ISW assessed that Russian forces advanced roughly 4,168 square kilometers in 2024, and Syrskyi’s statement indicates that Russian forces suffered approximately 104 casualties per square kilometer of advance in 2024.[6] Russian forces conducted multiple mechanized pushes in the latter half of 2024 to enable their gains but ultimately failed to restore operational maneuver to the battlefield in Ukraine. Russian forces ended 2024 and began 2025 by conducting grinding, infantry-heavy assaults in multiple areas of the battlefield in tactical envelopments and taking heavy personnel losses in the process.

Kharkiv-Luhansk axis

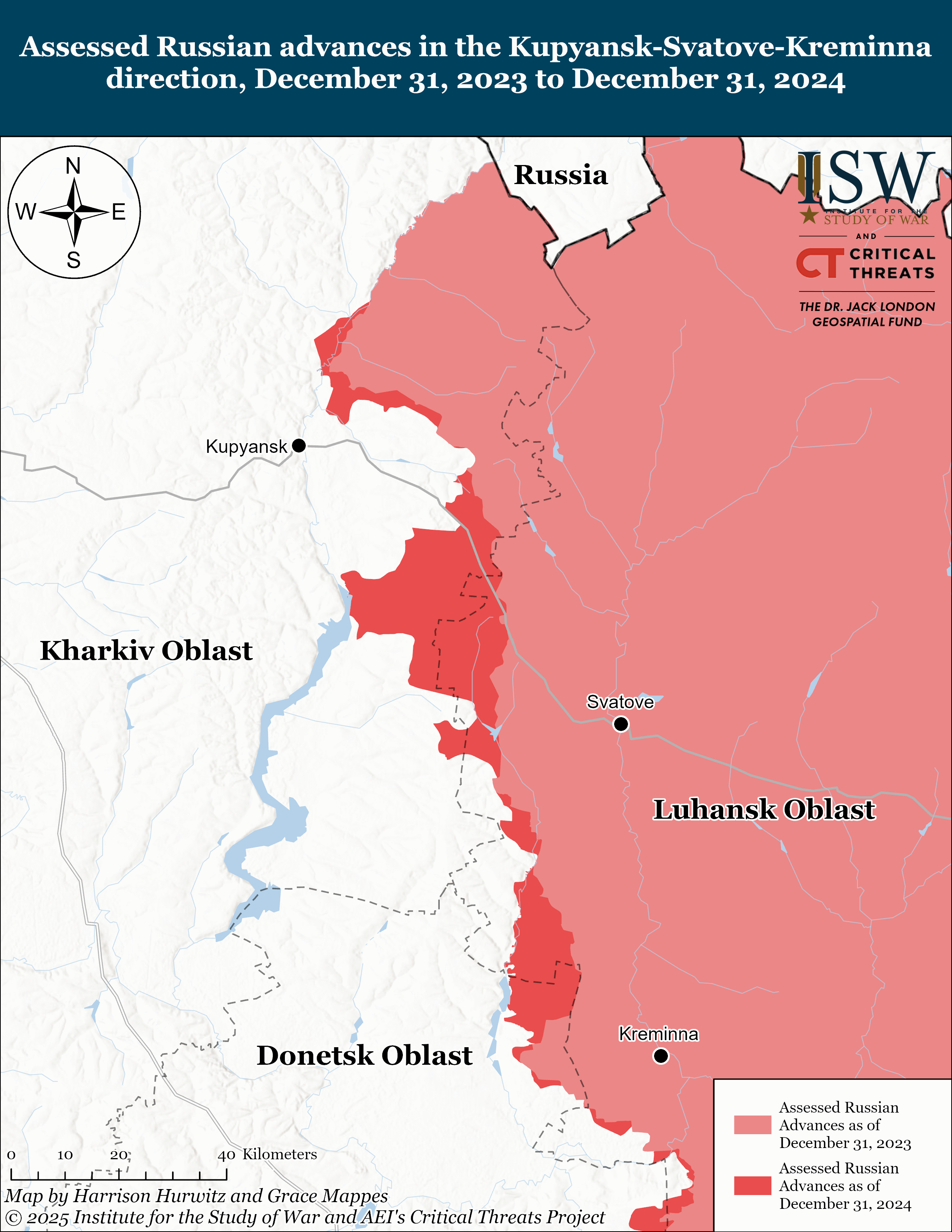

Russian forces attempted a multi-axis offensive operation on the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line in Winter 2023-2024, but this large effort quickly fizzled out into occasional offensive pushes. Russian forces intended this effort to be a cohesive operation across four distinct axes of advance: northeast of Kupyansk near Synkivka, southeast of Kupyansk towards Kruhlyakivka, southwest of Svatove towards Borova, and west and southwest of Kreminna towards Lyman – all to advance the Kremlin’s objective of seizing all of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.[7] This was the first cohesive Russian offensive effort across multiple axes since the initial invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and elements of the Moscow and Leningrad military districts (MMD and LMD, both formerly Western Military District [WMD]) were responsible for all four efforts on this line.[8] Russian forces failed to make significant gains along this line in the initial months of 2024, however, likely because Russian forces were unable to conduct the significant mechanized maneuver necessary to make such gains.[9] Russian forces occasionally conducted intensified offensive pushes in individual directions along the Kharkiv-Luhansk axis starting in Summer 2024 but could not simultaneously maintain multiple efforts.[10]

Russian forces revived their efforts to advance towards the Oskil River in the Borova direction in September 2024 likely to set conditions for the future envelopment of Ukrainian positions on the east (left) bank of the river.[11] Russia made a tactical breakthrough towards Kruhlyakivka in late August 2024 and eventually expanded their salient and reached the east (left) bank of the Oskil River in November 2024, bisecting the Ukrainian presence on the east bank.[12] Russian forces likely hoped that cutting the ground lines of communication (GLOCs) between Ukrainian forces operating in the area east of Kupyansk and those further south on the Svatove-Kreminna line in combination with striking Ukrainian crossings over the river would allow them to advance and envelop Ukrainian forces on the east bank more quickly.

Russian forces struggled to make significant gains anywhere along the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line after reaching the Oskil River southeast of Kupyansk, however. Russian forces gradually widened the Kruhlyakivka salient but failed to make more than marginal gains elsewhere on the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line in the following months. The Russian military command was and likely remains willing to accept gradual advances across the theater in Ukraine, however, and will likely continue pursuing its goals of pushing Ukrainian forces from the east bank of the Oskil River and seizing the remainder of Luhansk Oblast’s administrative boundaries along this axis.[13] Russian forces have recently made tactically significant advances during intensified offensive operations northeast of Kupyansk on the west (right) bank of the Oskil River near Dvorichna in January and February 2025.[14] Russian forces thus far have been conducting tactical envelopments of Ukrainian forces northeast of Dvorichna and likely hope to envelop Kupyansk from the north before attempting to advance further northwest towards Velykyi Burluk and unite the Kupyansk effort with their effort in northern Kharkiv Oblast.[15]

Avdiivka

Russian forces completed their two-year effort to seize Avdiivka in February 2024 following an arduous and costly campaign. Russian forces intensified their offensive operations in the Avdiivka area in October 2023 to increase their tempo of offensive operations across the theater after Ukrainian counteroffensive operations in western Zaporizhia Oblast slowed throughout September and October 2023.[16] Russian forces had conducted relatively little offensive activity around Avdiivka in Summer 2023, and ISW has previously assessed that the Russian military command likely chose to increase offensive operations around Avdiivka in Fall 2023 because Russian forces had set favorable conditions to encircle Avdiivka in a prior offensive operation during the Winter 2022-2023 offensive operation.[17] Russian forces initially began offensive operations near Avdiivka with multiple waves of battalion- to brigade-sized mechanized assaults, but these attacks initially failed to make tactically significant advances.[18]

Russian forces switched tactics to primarily conducting mass infantry assaults in the Avdiivka direction in November 2023 after suffering high vehicle losses, likely to maintain consistent offensive pressure on Ukrainian forces. Russian forces abandoned their efforts to encircle Avdiivka along with these mechanized pushes and began attritional infantry assaults with little to no armored vehicle support in the Avdiivka direction in mid-November 2023.[19] Russian forces did resume mechanized assaults near Avdiivka in late November, but at a smaller scale than the up-to-brigade-sized mechanized assaults in October.[20]

Russian forces set conditions in December 2023 and January 2024 to make tactically significant advances in the Avdiivka direction. Russian forces had redeployed the remaining elements of the Central Military District (CMD) from the Lyman direction to the Avdiivka direction by January 2024 and significantly intensified glide bomb strikes against Avdiivka in the first half of the month.[21] Russian forces intensified offensive efforts around Avdiivka around the same time as they launched the Winter-Spring 2024 offensive effort in Luhansk Oblast in mid-January 2025, likely to prevent Ukrainian forces from transferring manpower and materiel to defend against Russian advances in one area of the front, perhaps particularly the Avdiivka direction.[22] Russian forces abandoned efforts to encircle Avdiivka operationally (over a wide area) in January 2024, opted instead for direct frontal assaults, and achieved a tactical penetration into Avdiivka in early February.[23] Russian forces seized Avdiivka in mid-February 2024.[24]

The relatively successful envelopment of Avdiivka did, however, serve as a blueprint for Russian offensive operations elsewhere in the theater in the second half of 2024 and into 2025.[25] Russian forces began attempting tactical and operational level envelopments through attritional infantry assaults rather than encirclements. Russian forces seized Vuhledar in October 2024 and Velyka Novosilka in January 2025 by conducting envelopments that forced Ukrainian forces to withdraw from these settlements.[26] (An encirclement is a maneuver in which attacking forces completely surround and usually then capture or destroy an enemy grouping of forces.[27] An envelopment is a maneuver wherein attacking forces aim to avoid an enemy’s principal defenses to seize objectives behind those defenses that allow the attacking forces to force defenders to withdraw from their current positions or destroy them if they remain in place.)[28]

The battle for Avdiivka was brutal and the steep price Russia paid for its seizure prompted intense backlash from the Russian ultranationalist information space, undermining the Kremlin’s efforts to portray the seizure of Avdiivka as a significant victory to a domestic Russian audience. Forbes estimated that Russian forces may have lost up to 13,000 personnel killed and wounded near Avdiivka between mid-October and early December 2023, and a Ukrainian official estimated that Russian forces lost 20,607 personnel, 201 tanks (two tank brigades’ worth), and 492 armored fighting vehicles (AFVs) from January 1 to February 16, 2024.[29] Russian forces likely lost at least a battalion tactical group’s (BTG) worth of armored vehicles just in the first three days of renewed mechanized assaults near Avdiivka on October 10 to 12, 2023, and reportedly suffered 1,000 to 2,000 killed and wounded personnel near Avdiivka in the same time period.[30] Russian milbloggers were routinely critical of the Russian operation to seize Avdiivka, and the extent of this information space backlash prompted significant Kremlin efforts to coopt the milblogger community and censor complaints of Russian battlefield failures. Ukrainian military officials stated in October 2023 that Russian forces near Avdiivka were refusing to conduct assault operations due to extensive losses, and US officials stated that Russian military commanders ordered the executions of Russian soldiers who refused to fight near Avdiivka.[31]

Russian milbloggers claimed in October 2023 that Russian “Storm-Z” detachments, irregular assault units composed of penal recruits, were destroyed after just a few days of assaults in the Avdiivka direction and that the detachments lost between 40 and 70 percent of their personnel.[32] The milbloggers correctly attributed these high losses to the Russian military command’s poor conduct of the war overall, including inadequate training for new personnel, lack of artillery support for attacking forces, and poor communication and coordination with neighboring units. The information space outcry peaked in late February 2024, after prominent independent Russian milblogger Andrei Morozov (alias Boytsovskiy Kot Murz), who served in the Russian military, published a suicide note claiming that a Russian military commander had ordered him to remove a Telegram post in which Morozov claimed that nearly 16,000 Russian personnel died in combat for Avdiivka.[33] Morozov criticized the Russian military command, political leadership, and propagandists for hiding the battlefield reality and claimed that the Russian military command may have sought to kidnap or murder him. Morozov justified his suicide by claiming that he no longer wanted to continue fighting against the military bureaucracy and serving under a poor and abusive commander. The Russian information space largely coalesced around Morozov and blamed Russian military and political actors for his death.[34] A Russian milblogger recently claimed that “Storm-Z” detachments fighting in Donetsk Oblast continue to suffer high casualty rates and need to be completely restaffed within one or two months.[35]

Chasiv Yar

Russian forces have been conducting intensified offensive efforts to seize Chasiv Yar since May 2024 but still have not completely seized the town. The seizure of Chasiv Yar, itself a relatively small settlement, would be operationally significant since it would facilitate future Russian offensive operations directly against the critical fortified cities of Kostyantynivka, Druzhkivka, and Kramatorsk. Russian forces began their campaign for Chasiv Yar soon after seizing Bakhmut in May 2023 and conducted localized offensive operations from November 2023 to March 2024 to recapture areas that Ukrainian forces had seized during their Summer 2023 counteroffensive and to seize Chasiv Yar, likely to take advantage of weakened Ukrainian defenses in the area.[36] Ukrainian forces largely stalled the Russian offensive here, and Russian forces only made marginal gains in those four months.[37] ISW forecast in March 2024 that Russian forces were unlikely to seize Chasiv Yar rapidly, as Russian forces had not set conditions to envelop Chasiv Yar from its flanks – a tactic Russian forces have since successfully employed on other areas of the front.[38]

Russian forces entered Chasiv Yar from the east in April 2024 and re-intensified offensive operations against Chasiv Yar again in May 2024 with a series of mechanized assaults in the eastern part of the town.[39] The intensified Russian effort to seize Chasiv Yar has been characterized by attritional urban combat within Chasiv Yar itself, and Russian forces seized the eastern half of Chasiv Yar in July 2024. Russian gains in and around Chasiv Yar slowed in August and September 2024, but Russian forces managed to establish enduring positions on the west (right) bank of the Siverskyi Donets Donbas Canal both within and south of Chasiv Yar in October 2024. They still struggle to transport armored vehicles across the canal, however.[40] Russian forces continued attritional, predominantly infantry assaults in the area through Winter 2024-2025 and have seized most but not all of Chasiv Yar as of this publication without, however, setting good conditions to capitalize on these gains for future offensives in this area at this time.

The Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) could not have the Wagner Group take on the bulk of the effort and casualties for the Chasiv Yar effort as the Wagner Group did for Bakhmut because Wagner had been disbanded. The Wagner Group reportedly recruited at least 48,000 prisoners from Russian penal colonies to fight in Ukraine, largely for the Bakhmut effort, and reportedly lost 20,000 personnel, 17,000 of whom were penal recruits, in the fighting for Bakhmut.[41] The Wagner Group reportedly spent 108 billion rubles (about $1.18 billion) alone on death payments for deceased personnel, not including compensation for injuries or salaries.[42] This was money, recruitment efforts, and casualties that the Russian MoD did not have to expend itself to make attritional gains in the Bakhmut effort but now had to expend for the Chasiv Yar effort following the Wagner Group rebellion under then-Wagner Group financier Yevgeny Prigozhin.

The Russian force composition fighting for Chasiv Yar has remained largely consistent throughout the campaign, affording Russian forces in this area little of the rest and reconstitution necessary to make rapid gains. Elements of the Russian 51st Combined Arms Army (CAA) (formerly 1st Donetsk People’s Republic Army Corps [DNR AC], Southern Military District [SMD]), 3rd CAA (formerly 2nd Luhansk People’s Republic [LNR] AC, SMD), 98th Airborne (VDV) Division, and 200th Motorized Rifle Brigade (14th AC, LMD) as well as select Chechen Akhmat forces and Russian Volunteer Corps elements have comprised the bulk of the Russian forces participating in the fighting for Chasiv Yar since 2023.[43] The seizure of Chasiv Yar and the deployment of fresh forces or significant reconstitution of the forces already there would afford Russian forces several different opportunities for further offensive operations, including advancing on the Slovyansk-Kramatorsk-Kostyantynivka fortress belt, supporting an offensive effort in the Siversk direction, or evening out the frontline between the Chasiv Yar and Pokrovsk directions. Russian forces will likely continue struggling to make rapid gains and instead accept gradual, attritional gains for as long as they continue to make them, especially if the Russian force grouping continues these operations without adequate rest and reconstitution or reinforcement.

Northern Kharkiv Oblast

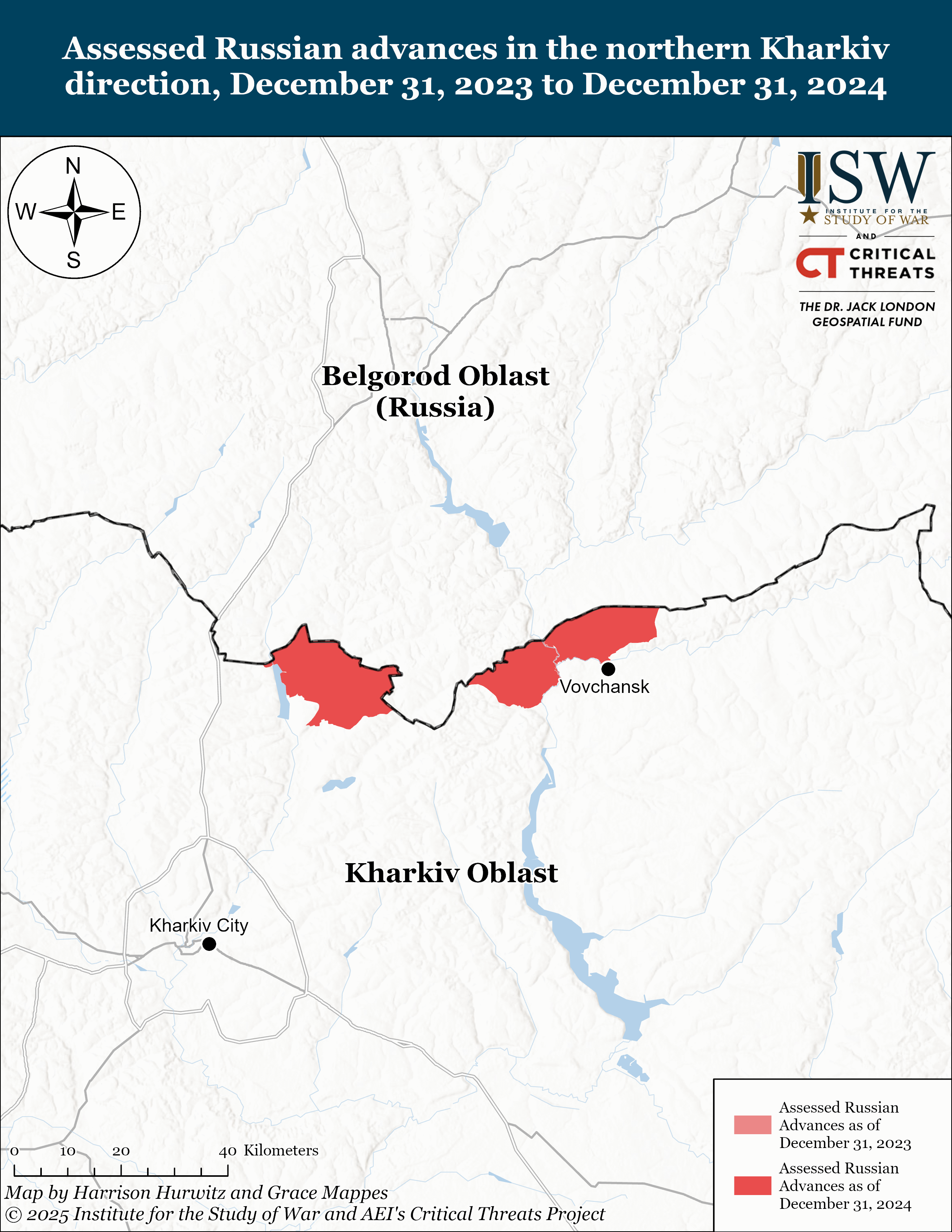

Russian forces launched an offensive into northern Kharkiv Oblast across the international border in early May 2024, likely in an effort to take advantage of the remaining time before renewed US military assistance – passed by the US Congress in April 2024 – reached frontline Ukrainian forces.[44] Russian forces committed limited manpower to heavy infantry assaults north and northeast of Kharkiv City on May 10 and initially made tactically significant gains north and northeast of Kharkiv City, but their pace quickly slowed.[45] Ukrainian officials announced that Ukrainian forces largely stabilized the situation along the northern border as of May 16.[46] Russian forces began transferring additional forces to the northern Kharkiv Oblast frontline by late May 2024, however, likely to draw and fix as many Ukrainian forces as possible and maintain a relatively high tempo of offensive operations in the area.[47] Zelensky stated that the casualty ratio of Russian forces to Ukrainian forces was eight-to-one in northern Kharkiv Oblast during the first two weeks of fighting.[48] Russian forces continued to slog towards Lyptsi north of Kharkiv City and within Vovchansk northeast of Kharkiv City but largely deprioritized the northern Kharkiv Oblast effort in August 2024. Russian forces stalled on the northern bank of the Vovcha River within Vovchansk and still have not reached Lyptsi, which is roughly eight kilometers from the border, as of February 2025.

Russian forces likely launched their offensive north and northeast of Kharkiv City prematurely to fix Ukrainian forces at the northern border in support of Russian offensives elsewhere in eastern Ukraine. Russian forces initially attacked with limited elements of the 11th AC and 44th AC (both LMD]) and expanded to include elements of the 6th CAA (LMD) in the following weeks.[49] The Russian Northern Grouping of Forces was reportedly understrength in May 2024, however, only having 35,000 personnel of its planned 50,000 to 70,000 end strength in the international border area upon starting offensive operations in May 2024.[50] Russian forces did succeed in fixing Ukrainian forces here while intensifying offensive operations elsewhere in the theater.[51] The Russian military command deprioritized this sector of the front and transferred forces that were either operating or soon intended to operate along the northern Kharkiv frontline to defend against the Ukrainian incursion into Kursk Oblast in August 2024.[52]

The Kremlin initially signaled its intent to attack across Ukraine’s northern border by promoting the idea of a demilitarized “sanitary zone,” which Putin first introduced in January 2024 and other senior Kremlin officials continued promoting throughout Spring 2024.[53] Kremlin officials claimed that Russian forces had to push the frontline farther into unoccupied Ukraine, explicitly including Kharkiv Oblast, to place Russian settlements outside of Ukrainian strike range, but the vague definition of this buffer zone provides an informational justification to attempt to seize most if not all of Ukrainian-held territory. The Kremlin likely also intended to use this narrative to deter further Western military assistance to Ukraine, justify the war to its domestic population, and allow Russian forces in northern Kharkiv Oblast and elsewhere to take advantage of weakened Ukrainian defensive capabilities. The Kremlin largely dropped this rhetorical line in Fall 2024 after the battlefield focus shifted to Kursk Oblast and eastern Ukraine.

Toretsk

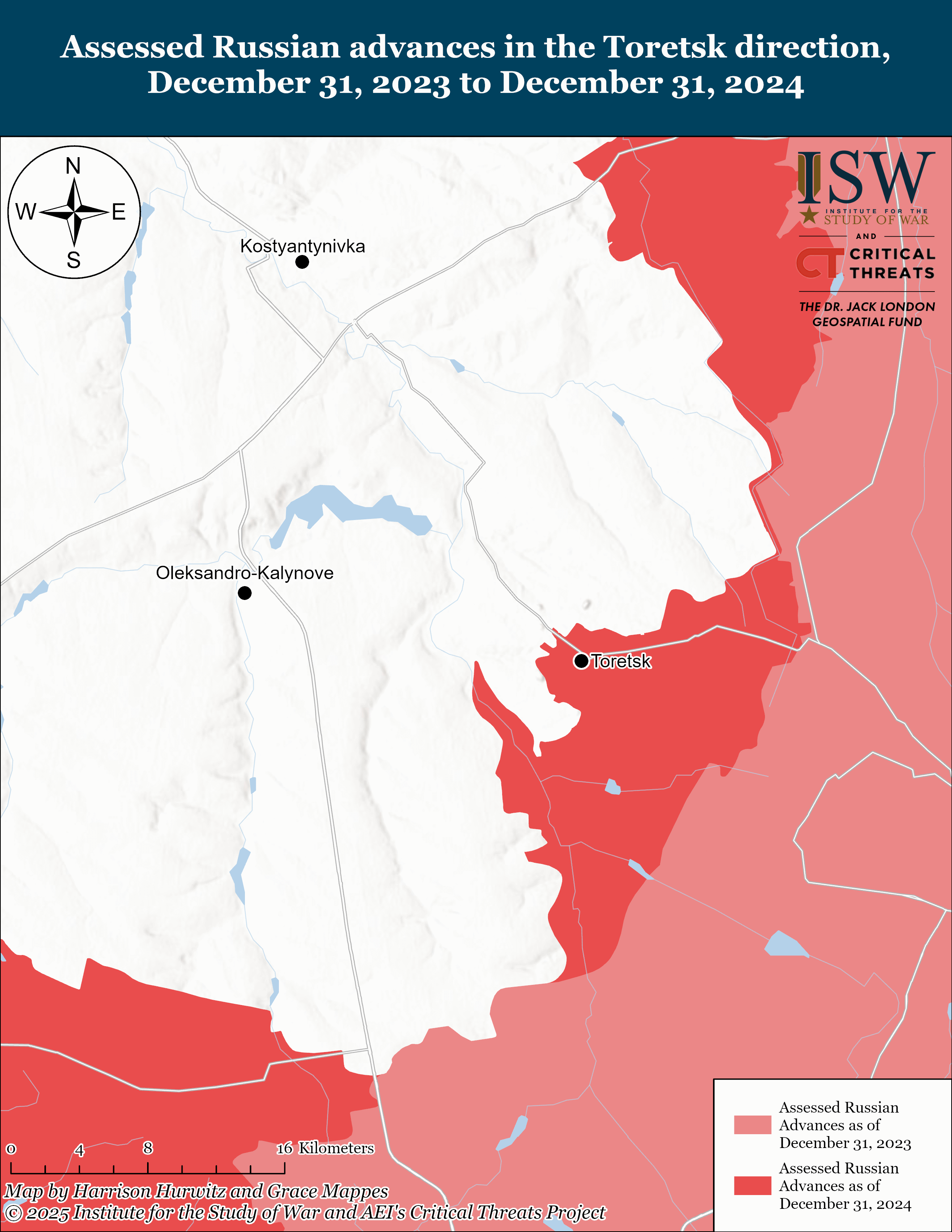

Russian forces intensified localized offensive operations in the Toretsk direction in mid-June 2024 after having been generally inactive in this area since the start of the full-scale invasion in February 2022. Russian forces likely aimed to reduce the Ukrainian salient in the Toretsk direction, as the prospect of Ukrainian fires or counterattacks from the Toretsk salient threatened the Russian flanks in the Chasiv Yar and Avdiivka/Pokrovsk directions the more that Russian forces made gains in those areas without making similar gains in the Toretsk direction. Russian forces made only marginal gains east of Toretsk in the initial weeks of this effort and dedicated limited manpower to this area, indicating that Russian forces continued to prioritize gradual, attritional advances over attempting more rapid gains.[54] Elements of one motorized rifle brigade of the Russian 51st CAA and of two motorized rifle regiments of the Russian Territorial Troops were the main forces committed to these initial offensive operations, units that are generally less combat-effective than conventional Russian forces.[55] The Russian military command assigned elements of the CMD to the Toretsk effort by late July 2024, including by redeploying the majority of its 27th Motorized Rifle Division from the Avdiivka direction to conduct assaults south of Toretsk near Niu York.[56] This redeployment was part of a wider expansion of the CMD’s area of responsibility (AoR) from the Avdiivka direction alone to the bulk of Donetsk Oblast.[57]

Russian forces have continued to make gradual gains in the Toretsk direction across Fall 2024 and Winter 2024-2025 but largely did not prioritize this direction in 2024. Russian forces seized Niu York, which has been on the frontline since 2014, in August 2024, and have continued to gradually advance east and south of Toretsk into the town primarily by conducting infantry assaults.[58] Russian forces have seized most of Toretsk as of this publication but have not made or attempted to make significant gains beyond it. Russian forces may prioritize this direction in the anticipated Spring-Summer 2025 offensive operation to level the frontline between the Chasiv Yar and Pokrovsk directions and set conditions to attack the southern edge of the Ukrainian fortress belt at Kostyantynivka and have recently begun transferring some forces to the Toretsk direction from the other directions in Donetsk Oblast possibly for this aim.[59]

Marinka-Kurakhove

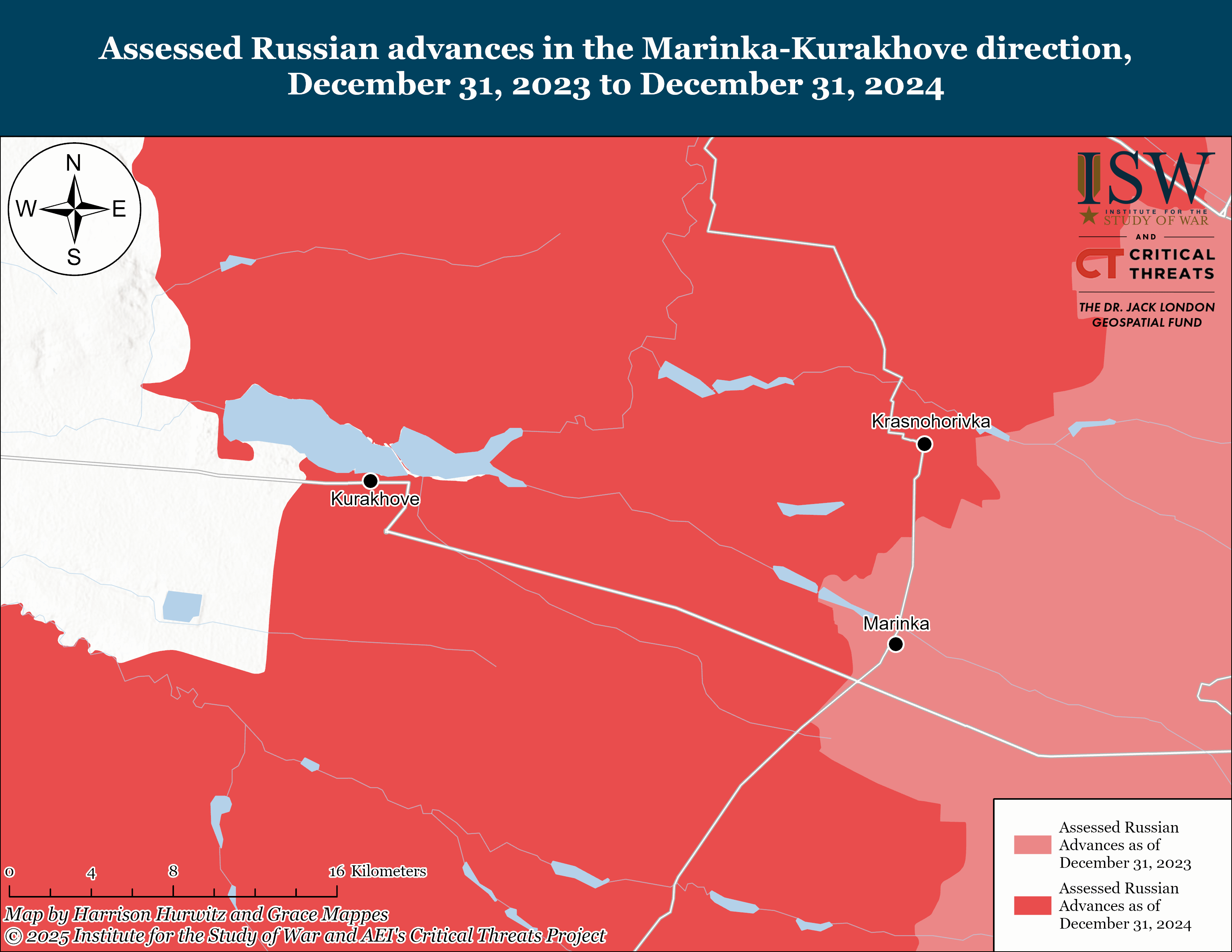

Russian forces took a year to advance roughly 11 kilometers from Marinka to Kurakhove and seize the latter settlement in December 2024.[60] Russian forces intensified offensive operations towards Kurakhove in late July 2024 and conducted several roughly company-, platoon-, and battalion-sized mechanized assaults west and southwest of Donetsk City within five days in late July, the largest Russian mechanized assaults in Ukraine between October 2023 and July 2024.[61] Ukrainian forces largely blunted these attacks and inflicted heavy armored vehicle and personnel losses on Russian forces. Russian forces likely intended to cut the T-0524 Vuhledar-Kostyantynivka highway southwest of Marinka to force Ukrainian forces to withdraw from the area.

The intensified Russian mechanized assaults in the Kurakhove direction in July 2024 marked the start of a dedicated Russian effort to advance along multiple operational axes on the southern flank in Donetsk Oblast while suffering high equipment and personnel losses. Russian forces conducted periodic platoon- and company-sized attacks throughout the Donetsk Oblast frontline in Summer 2024, all of which quickly turned into attritional infantry assaults.[62] Russian forces struggled to conduct these mechanized pushes in more than one area of the frontline simultaneously and likely conducted them opportunistically in attempts to exploit weak spots in Ukraine’s defense, degrade Ukraine’s defensive capabilities, and achieve limited territorial advances, partly for informational purposes.[63] The Russian intensification in the Kurakhove direction indicated that the Russian military command was willing to accept costly armored vehicle losses without conducting a large-scale, multi-directional offensive operation or making operationally significant advances, and proved burdensome to the Russian military as ISW has previously assessed.[64]

Russian forces began grinding efforts to close Ukrainian pockets along these mutually reinforcing efforts in October-November 2024 to advance on Kurakhove and successfully level the frontline.[65] These advances towards Kurakhove from the east intended to level the frontline between Pokrovsk and Vuhledar, and Russian forces took advantage of the seizure of Vuhledar in early October 2024 to advance on Kurakhove from the southwest and of the seizure of Selydove in late October to advance on Kurakhove from the north.[66] Russian forces managed to collapse a tactical Ukrainian pocket on the Ukrainsk-Hirnyk-Kurakhivka line northeast of Kurakhove in October 2024.[67] Russian forces began forming a pocket around Kurakhove from the north along the Hirnyk-Sontsivka-Petropavlivka line and from the south along the Pobieda-Dalne line in November 2024 but struggled to force Ukrainian forces to withdraw from Kurakhove by closing the pocket. Russian forces became bogged down in direct assaults within Kurakhove itself in mid-October 2024 before seizing the settlement in late December 2024.[68] Russian forces have largely struggled to close a small Ukrainian pocket west of Kurakhove along the Dachne-Andriivka line in January and February 2025, likely due to degraded combat capabilities from months of ongoing offensive efforts, completing the effort only on February 21.[69]

Russian forces reportedly concentrated up to 36,000 personnel in the Kurakhove direction in the months leading up to seizing it and conducted multiple mechanized assaults in pushes to seize the settlement, likely taking significant personnel and materiel losses.[70] Russian forces struggled to make rapid advances further west of Kurakhove in the beginning weeks of 2025 and have significantly reduced the number of armored vehicles fielded likely due to extensive losses and possibly due to increasing shortages of armored vehicles.[71] Russian forces reportedly redeployed elements of the 51st CAA as well as the 90th Tank Division (41st CAA, CMD), from the Kurakhove direction to elsewhere in Donetsk Oblast in January and February 2025, indicating that the Russian military command may be prioritizing a new offensive effort elsewhere over further advances west of Kurakhove in the near term.[72]

Pokrovsk

The year-long Russian effort to seize Pokrovsk has so far failed, and Russian forces appear to have abandoned the effort to take the city directly, preferring instead to conduct a wide envelopment. The Kremlin may have abandoned even that effort for now, however, in the fact of increasing Ukrainian resistance in the area and extremely high Russian losses. Russian forces first renewed offensive operations towards Pokrovsk in late February 2024 after a several-day pause following the seizure of Avdiivka.[73] Elements of the Russian 51st CAA were tasked with exploiting the seizure of Avdiivka and making further gains west, and Russian forces resumed their high tempo of assaults in late February and early March 2024, likely intending to conduct frontal assaults directly against Pokrovsk.[74] Russian forces took advantage of Ukrainian manpower and materiel constraints exacerbated by delays in Western-provided military assistance from March to June 2024 to advance west of Avdiivka towards Pokrovsk.[75] The likely Russian primary offensive effort for Summer 2024 was a direct assault on Pokrovsk following the Avdiivka-Ocheretyne-Zhelanne-Novohrovika-Pokrovsk railway line along which Russian forces advanced during Spring and Summer 2024 after reportedly exploiting a botched Ukrainian rotation near Ocheretyne in late April 2024 and achieving a narrow penetration.[76] Russian advances in May and June 2024 forced Ukrainian forces to withdraw to the east (left) bank of the Vovcha River, and Ukrainian forces had to withdraw across the river by August 2024.[77] Ukrainian officials described Russia’s significant artillery and air support as the largest factors contributing to Russian forces’ advance west of Avdiivka in this time period and noted that Russian forces rarely conducted mechanized assaults, instead advancing in infantry assaults using ATVs or motorcycles.[78] Russian forces likely fielded fewer mechanized vehicles in the Pokrovsk direction in this time due to the heavy losses incurred in earlier fights for Avdiivka and elsewhere. Russian advances on Pokrovsk from the east slowed over the summer and stalled in September 2024 as the Russian military command reallocated assets to the Selydove direction and elsewhere in Donetsk Oblast.[79] The Russian military command appears to have given up the effort to take Pokrovsk directly or through narrow envelopment at this time.

Russian forces likely redesigned their campaign to seize Pokrovsk through a wider envelopment in July and August 2024, starting a towards Selydove southeast of Pokrovsk.[80] Russian forces forced Ukrainian forces to withdraw from Hrodivka and Novohrodivka in late August 2024 via turning movements instead of having to conduct costly frontal assaults against well-fortified Ukrainian positions. The Russian military command had likely decided to level the frontline by seizing Selydove, Vuhledar, and Kurakhove before launching intensified offensive operations against Pokrovsk itself.[81] Russian forces seized Selydove in late October 2024 and exploited this seizure to make further gains near Pokrovsk.[82] Russian forces suffered their greatest casualty rates in the war up until this point in Fall-Winter 2024, and the Russian military command was likely willing to accept these high casualties in exchange for relatively rapid territorial advances. Russian forces reportedly suffered a record average of 1,523 personnel casualties per day in November 2024 and this loss rate reportedly increased to an average of 1,585 casualties per day in December 2024.[83]

Russian forces reprioritized the Pokrovsk direction in January 2025. Russian forces assembled a strike group of elements of the 2nd and 41st CAAs (both CMD) southwest of Pokrovsk by mid-January and reportedly redeployed elements of the 51st CAA and 8th CAA (both SMD) from the Kurakhove direction to the Pokrovsk direction in January and February 2025, respectively.[84] Russian forces are likely attempting to envelop Pokrovsk from the west, but these advances will likely take months at the current Russian rate of advance in the area if they succeed at all. Russian forces cut the T-0504 Pokrovsk-Kostyantynivka highway east of Pokrovsk and the T-0406 Pokrovsk-Mezhova highway southwest of Pokrovsk in mid-January 2025 as part of these envelopment efforts but notably have not made significant advances beyond these highways in the following weeks.[85] The Russian rate of advance near Pokrovsk slowed in the first two weeks of February 2025, suggesting that the Russian military command may be deprioritizing offensive operations near Pokrovsk at least for now.[86] Russian advances south of Pokrovsk may be slowing due to the degradation of forces fighting on the frontline, however, as Russian forces reportedly suffered 7,000 killed in action just in the Pokrovsk direction in January 2025.[87]

The Russian advances in the Pokrovsk direction since the seizure of Avdiivka have largely not followed the Avdiivka blueprint but are instead emblematic of the Russian military learning throughout three years of war. Russian forces fighting for Avdiivka relied on heavy and frequent mechanized assaults, which Russian forces have not been able to conduct in further operations in the Pokrovsk effort due to the unsustainable vehicle loss rate.[88] Russian forces also lack the extreme artillery advantage they held over Ukrainian forces during the final months of the Avdiivka campaign and have not been conducting heavy glide bomb strikes to set conditions for ground operations against obliterated urban defenses. Russian forces’ previous 5:1 artillery advantage over Ukrainian forces was reduced to a 1.5:1 artillery advantage as of December 2024, for example.[89] Russian forces have made gains in the Pokrovsk direction by exploiting weaknesses in Ukrainian defenses and utilizing the most effective tactics for the current battlespace.[90] Ukrainian soldiers and some Russian sources have attributed Russian successes near Pokrovsk to conducting assaults with small, fire-team sized groups and using windbreaks and buildings for cover against Ukrainian drone operations, approaches that are nevertheless constraining Russian forces’ ability to concentrate for frontal assaults with larger groups.[91]

Vuhledar-Velyka Novosilka

Russian forces seized Vuhledar in October 2024 after a two-year effort fraught with high losses and repeated tactical failures. Russia’s attritional Winter 2022-2023 effort provoked significant backlash in the Russian information space and significantly degraded the Russian forces participating in the assault, most notably the 155th Naval Infantry Brigade (Pacific Fleet), which reportedly had to be reconstituted eight times between February 2022 and March 2023 largely due to losses sustained in offensive operations in the Vuhledar area.[92] Russian forces periodically intensified offensive efforts against Vuhledar in 2023 and 2024, frequently sustaining heavy losses and evoking wrath in the Russian information space. Russian forces renewed a sustained offensive effort against Vuhledar in August 2024 and successfully enveloped and seized the settlement in October 2024, likely drawing from lessons learned in the envelopment of Avdiivka and exploiting Russian gains in the Kurakhove and Pokrovsk directions.[93]

Russian forces intensified assaults in the Velyka Novosilka direction in early November 2024. The Russian seizure of Vuhledar and further gains to the northwest allowed Russian forces to exploit Ukrainian defenses near Velyka Novosilka. Russian forces bypassed Velyka Novosilka from the east in lieu of conducting frontal assaults from the south, but Ukrainian defenses in the area were reportedly optimized to defend against those frontal assaults from the south. Russian forces continued efforts to break past Ukrainian forces north of Velyka Novosilka and reportedly temporarily seized Novyi Komar in early December 2024. Ukrainian forces pushed Russian forces from Novyi Komar shortly thereafter, but Russian sources claimed that Russian forces recaptured Novyi Komar by mid-December 2024.[94] Russian forces also seized Blahodatne south of Velyka Novosilka in early December 2024 and began advancing further south of the settlement.[95] Russian forces seized Vremivka immediately east of Velyka Novosilka on January 17 and seized Velyka Novosilka itself in late January.[96] The Russian MoD and information space largely played up the seizure of Velyka Novosilka as a significant informational victory for Russian forces as Russian forces recaptured much of the territory that Ukrainian forces had liberated in the area during their Summer 2023 counteroffensive.[97]

The Russian seizure of Velyka Novosilka helped Russian forces level the frontline in the Kurakhove, Vuhledar, and Velyka Novosilka directions, freeing up combat power for further offensive operations in Donetsk Oblast, particularly as the Russian military command prepares for its anticipated Spring-Summer 2025 offensive operations. Elements of the Eastern Military District (EMD) were largely responsible for this area of the front.[98] Russian forces could redeploy these EMD elements to other priority sectors, such as the Pokrovsk or Toretsk directions, or could have the EMD continue to press towards the Dnipropetrovsk Oblast administrative border for informationally-significant gains.[99] Russian forces could also keep some EMD elements in the Velyka Novosilka area while redeploying the remainder to pin Ukrainian forces here. These EMD elements are likely degraded after months of combat such that their combat effectiveness and ability to make rapid advances in any offensive effort in the near term is unclear. Redeployments of elements of the EMD to areas elsewhere on the frontline are an indicator of the Russian military command’s priority areas for Spring-Summer 2025.[100]

Kursk Oblast

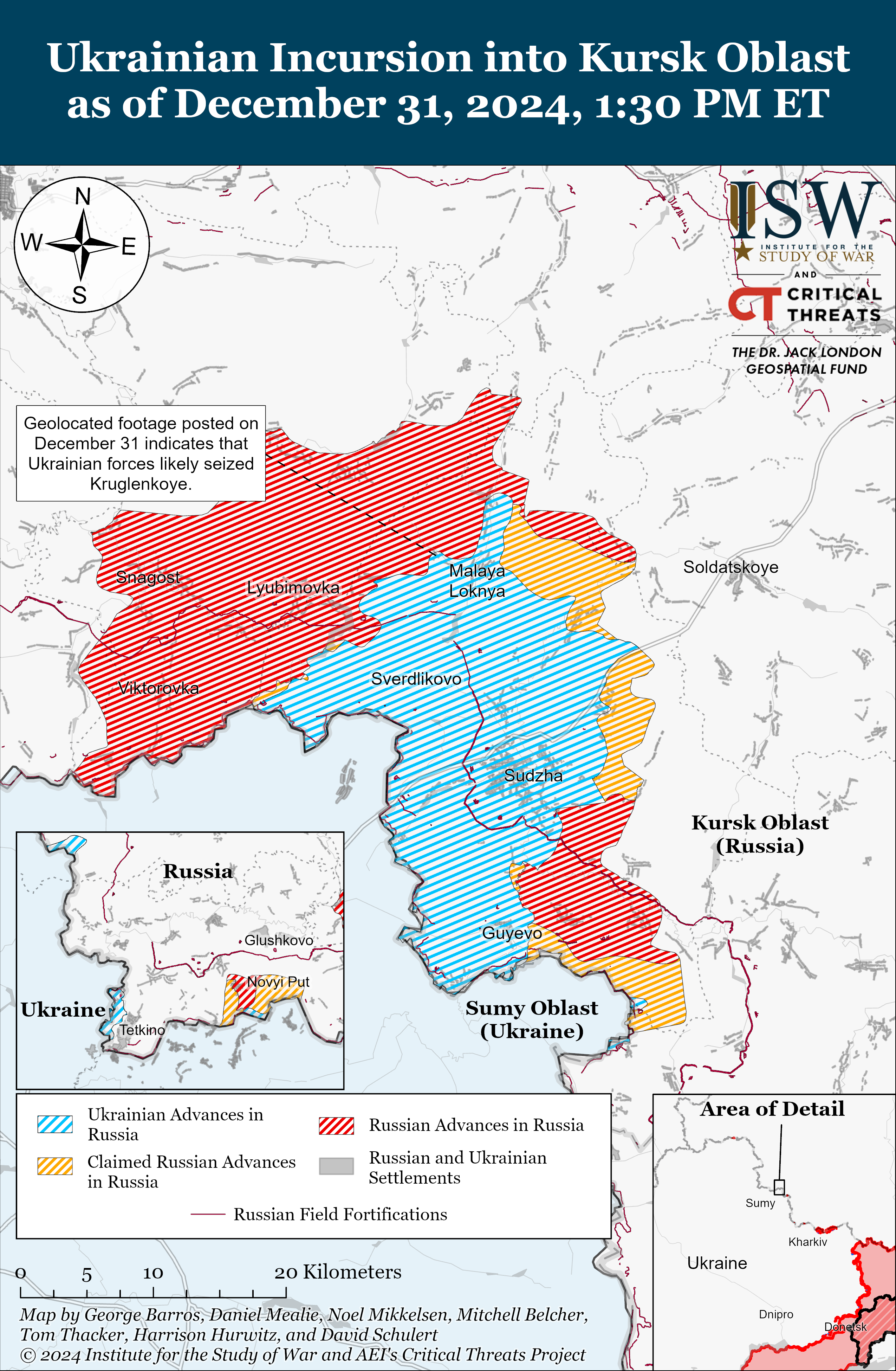

Ukrainian forces launched their incursion into Kursk Oblast in early August 2024, forcing Russian forces to divert manpower and resources from across the theater to defend against it. The Russian defense in the initial days of the incursion was disorganized and confused; the Kremlin had failed to adequately man the border with Ukraine, leaving this task to conscripts, FSB border guards, and Rosgvardia personnel.[101] The roughly 11,000 Russian personnel in Kursk Oblast at the start of the incursion were poorly trained and ill-equipped and were surprised by the time and manner of the Ukrainian incursion, which seized an area of 1,153 square kilometers as of September 6, 2024, including the town of Sudzha, which became the base of Ukrainian operations in the salient.[102] The Russian military command quickly redeployed forces from across the theater to stabilize the line in late August 2024 after Ukrainian forces achieved an operational penetration. Elements of the LMD redeployed from northern Kharkiv Oblast, Chechen forces from unspecified rear or frontline areas, irregular Russian units from frontline areas including in Donetsk Oblast, and additional conscripts from garrisons within Russia and arrived in late August.[103] The Russian military command even reportedly redeployed at least a company of the 15th Motorized Rifle Brigade (2nd CAA) from the Pokrovsk direction to Kursk Oblast in late August 2024, which ISW has previously assessed indicates that the Russian military struggled briefly to insulate its priority offensive operation from the theater-wide impacts of the Kursk incursion.[104] Russian forces also redeployed naval infantry elements and additional VDV elements from Kharkiv, Donetsk, and Zaporizhia oblasts within the first month of the incursion and appear to have tasked these combat-experienced elements with leading conscripts and other less-trained units in Kursk Oblast.[105] Ukrainian officials estimated that 30,000 to 45,000 Russian personnel had concentrated in Kursk Oblast as of mid-September 2024.[106]

Russian forces conducted several phases of limited counterattacks in an attempt to bisect the main Ukrainian salient in Kursk Oblast and eliminate the western part of the salient. Russian forces conducted mechanized counterattacks in the western part of the salient near Korenevo in early September, mid- and late-October, early November, and early December 2024, all intended to bisect the main Ukrainian salient, but failed to make significant gains in each phase.[107] Russian forces focused on attritional infantry assaults to make creeping but steady gains in most of November and December 2024 and introduced 11,000 to 12,000 North Korean forces into combat in November but have since taken high losses.[108] Russian forces again intensified efforts to push Ukrainian forces from the salient again in January 2025, particularly west, east, and south of Sudzha, likely in preparation for a future offensive operation to seize Sudzha itself, and have concentrated roughly 78,000 total personnel in Kursk Oblast as of February 2025.[109]

Ukraine’s incursion into Kursk Oblast has drawn and fixed Russian forces to the area and reportedly spoiled several Russian offensive efforts. Ukrainian officials warned about Russian preparations for possible offensive efforts in 2024 and have since stated that the Kursk Oblast incursion complicated Russian efforts to intensify offensive operations in northern Kharkiv, Donetsk, and Zaporizhia oblasts.[110] The Kursk Oblast incursion also highlighted Russia’s inability to rapidly respond to unexpected Ukrainian activity in one sector of the front without limiting or deprioritizing another sector and has prevented experienced Russian VDV and naval infantry units from redeploying to support offensive operations in priority areas and drawn significant amounts of equipment from operations in Ukraine.[111]

Implications

Russian forces failed to break Ukraine despite expending tremendous military, human, and economic resources to multiple offensive efforts. Ukrainian forces continue to deny Russian forces the ability to routinely stage massive assaults in most areas of the front, forcing Russian forces to conduct the majority of their assaults in small infantry groups rather than significant mechanized or even motorized pushes.[112] Ukrainian forces blunted many of the Russian offensive operations and drove Russian forces to sustain these casualties for their slow and limited gains.[113] Ukrainian forces are conducting their own strike campaign to degrade Russian offensive and defense industrial capabilities, chiefly targeting energy and oil infrastructure but also including Russian military command posts, airbases, and force concentrations.[114] Ukrainian forces launched their incursion into Kursk Oblast which has drawn and fixed Russian forces from across the theater, reportedly spoiled additional Russian offensive pushes across Ukraine’s northern border, and forced Russia to rely on North Korean military personnel to defend its territory.[115] Russian forces continue to make tactical gains, especially in Russia’s priority sectors of the frontline, but Ukraine’s defense has forced Russian forces to pay substantial costs for advances that remain far below a rate normal for modern mechanized militaries and that are not sustainable in the medium term. Russia’s offensive operations as of Winter 2024-2025 are slowing down and do not threaten to break the Ukrainian frontline anytime in the near term, assuming US and Western support continues.

The scale of the Russian manpower and materiel losses in 2024 have set conditions for several material and manpower constraints in 2025 and beyond, as ISW has recently reported.[116] The Russian defense industrial base (DIB) cannot keep up with the pace of armored vehicle and artillery shortages, and Russia is unlikely to be able to recruit the manpower it needs to continue sustaining these losses without another round of partial mobilization, which the Kremlin remains reluctant to conduct.[117] Russia’s liquid financial reserves and economy writ large are unlikely to be able to support Russia’s current loss rates for another two years.[118] Russia’s losses are mounting and will generate opportunities for the US and Ukraine to extract a deal from Russia that benefits US national security. The West should continue supporting Ukraine to maintain the loss rate that can provide the US leverage in negotiations.

The last year of the war has been a gloomy one for Ukraine, which has been forced to stand on the defensive and absorb continuous and intensive Russian offensive operations as well as increasingly effective Russian drone and missile strikes on critical infrastructure. But the gloom has obscured an important reality: The Kremlin threw everything it had at breaking Ukraine in 2024 and failed. Ukrainian forces held in the face of Russian assaults conducted with a shocking disregard for losses in men and equipment and despite shortages imposed by delays in the provision of Western equipment. The front line remains fragile, and Russian forces can continue their pressure for many months to come. The end of US and Western support could lead to a relatively rapid collapse of Ukraine’s defense. But the key lessons from 2024 are that Ukraine can withstand enormous Russian pressures, on the one hand, and that the Kremlin has not figured out how to convert its overall numerical advantages into decisive battlefield gains. These lessons should guide Western thinking about the war and Ukraine’s prospects throughout any negotiations. They should above all guide thinking about the prospects of developing a post-war Ukrainian military into a force that can deter future Russian aggression with reasonable levels of Western support and commitment.

[1] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russias-weakness-offers-leverage

[2] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russia-ukraine-warning-update-russia-likely-pursue-phased-invasion-unoccupied-ukrainian ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar033023; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukrainian-defense-pokrovsk-has-compelled-russia-change-its-approach-eastern-ukraine

[3] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-november-24-2024

[4] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-31-2024

[5] https://isw.pub/UkrWar020525

[6] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-31-2024

[7] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-winter-spring-2024-offensive-operation-kharkiv-luhansk-axis; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/how-delays-western-aid-gave-russia-initiative-ukrainian-counteroffensive-kharkiv

[8] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-winter-spring-2024-offensive-operation-kharkiv-luhansk-axis; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/how-delays-western-aid-gave-russia-initiative-ukrainian-counteroffensive-kharkiv

[9] https://isw.pub/UkrWar050324 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar041824

[10] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/how-delays-western-aid-gave-russia-initiative-ukrainian-counteroffensive-kharkiv ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-june-22-2024 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-july-30-2024

[11] https://isw.pub/UkrWar092724

[12] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-august-28-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-30-2024

[13] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-31-2025

[14] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-31-2025;

[15] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-31-2025;

[16] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-12-2023; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukrainian-defense-pokrovsk-has-compelled-russia-change-its-approach-eastern-ukraine

[17] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/how-delays-western-aid-gave-russia-initiative-ukrainian-counteroffensive-kharkiv

[18] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-12-2023; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-15-2023; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-11-2023; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-10-2023

[19] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-november-13-2023; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-november-14-2023; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukrainian-defense-pokrovsk-has-compelled-russia-change-its-approach-eastern-ukraine; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/how-delays-western-aid-gave-russia-initiative-ukrainian-counteroffensive-kharkiv

[20] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/how-delays-western-aid-gave-russia-initiative-ukrainian-counteroffensive-kharkiv; https://isw.pub/UkrWar112423

[21] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/how-delays-western-aid-gave-russia-initiative-ukrainian-counteroffensive-kharkiv

[22] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/how-delays-western-aid-gave-russia-initiative-ukrainian-counteroffensive-kharkiv

[23] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-8-2024 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-2-2024 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar021524

[24] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-17-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-15-2024

[25] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-31-2025

[26] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-31-2025; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-1-2024

[27] https://www.moore.army.mil/infantry/doctrinesupplement/atp3-21.8/PDFs/fm3_90_2.pdf; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-15-2024

[28] https://www.moore.army.mil/infantry/doctrinesupplement/atp3-21.8/PDFs/fm3_90_2.pdf; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-15-2024

[29] https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidaxe/2024/01/30/russian-troops-crawled-through-a-sewer-to-attack-avdiivka-ukrainian-drones-were-waiting-for-them/?sh=7c31bffa5cca; https://www.pravda dot com.ua/eng/news/2024/02/17/7442379/

[30] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-12-2023; https://twitter.com/Osinttechnical/status/1712341762860032128; https://twitter.com/Tatarigami_UA/status/1712385378676514861; https://twitter.com/Tatarigami_UA/status/1712385380509487455; https://twitter.com/Tatarigami_UA/status/1712385382451437885; https://twitter.com/Tatarigami_UA/status/1712385384380862765; https://twitter.com/Tatarigami_UA/status/1712385386251477197; https://twitter.com/Tatarigami_UA/status/1712385388638302329; https://twitter.com/Tatarigami_UA/status/1712385391003656541; https://www.kyivpost dot com/post/22706

[31] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-67234144

[32] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-30-2023; https://t.me/philologist_zov/657 ; https://t.me/vozhak_Z/483 ; https://twitter.com/GirkinGirkin/status/1718843954353852713

[33] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-21-2024

[34] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-21-2024

[35] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-21-2025; https://t.me/pgubarev/1210; https://x.com/wartranslated/status/1892922843303678125

[36] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-march-24-2024

[37] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-march-24-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukrainian-defense-pokrovsk-has-compelled-russia-change-its-approach-eastern-ukraine

[38] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-march-24-2024

[39] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-may-18-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-august-27-2024

[40] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-31-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-17-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-november-26-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-31-2024

[41] https://zona dot media/article/2024/06/10/42174

[42] https://zona dot media/article/2024/06/10/42174

[43] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-may-12-2023 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-10-2023 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-19-2023 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-26-2023 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-28-2023 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-30-2023 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-september-30-2023

[44] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/how-delays-western-aid-gave-russia-initiative-ukrainian-counteroffensive-kharkiv

[45] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/how-delays-western-aid-gave-russia-initiative-ukrainian-counteroffensive-kharkiv; https://isw.pub/UkrWar051424 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar051324 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-may-12-2024 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar051124 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-may-16-2024 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar051024;

[46] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-may-16-2024

[47] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-may-30-2024

[48] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-may-25-2024; https://suspilne.media/753931-zelenskij-nazvav-vtrati-rosian-na-pivnoci-harkivsini/

[49] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-may-11-2024

[50] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-may-25-2024

[51] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/how-delays-western-aid-gave-russia-initiative-ukrainian-counteroffensive-kharkiv

[52] https://isw.pub/UkrWar082224; https://isw.pub/UkrWar081124

[53] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-31-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-4-2025; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-may-18-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-march-1-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-march-18-2024

[54] https://isw.pub/UkrWar06272024

[55] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-june-27-2024

[56] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-july-26-2024

[57] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-july-26-2024

[58] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-7-2025

[59] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-26-2025; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-16-2025

[60] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-26-2023; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-26-2024

[61] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-july-30-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-july-25-2024

[62] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukrainian-defense-pokrovsk-has-compelled-russia-change-its-approach-eastern-ukraine; https://isw.pub/UkrWar073024 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-august-17-2024

[63] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-july-30-2024

[64] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-july-30-2024

[65] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-november-24-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-november-25-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukrainian-defense-pokrovsk-has-compelled-russia-change-its-approach-eastern-ukraine

[66] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukrainian-defense-pokrovsk-has-compelled-russia-change-its-approach-eastern-ukraine; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-1-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-30-2024

[67] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-10-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-31-2024

[68] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-26-2024

[69] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-16-2025; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-31-2025; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-21-2025

[70] https://isw.pub/UkrWar122624

[71] https://isw.pub/UkrWar010425; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-15-2025

[72] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-8-2025; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-18-2025;

[73] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukrainian-defense-pokrovsk-has-compelled-russia-change-its-approach-eastern-ukraine

[74] https://isw.pub/UkrWar021924 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar021724 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-27-2024

[75] https://isw.pub/UkrWar032124 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar042724; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukrainian-defense-pokrovsk-has-compelled-russia-change-its-approach-eastern-ukraine

[76] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukrainian-defense-pokrovsk-has-compelled-russia-change-its-approach-eastern-ukraine; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-april-24-2024 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar031324 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-april-29-2024

[77] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukrainian-defense-pokrovsk-has-compelled-russia-change-its-approach-eastern-ukraine

[78] https://isw.pub/UkrWar051024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-may-28-2024 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-may-31-2024 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-june-9-2024 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-june-18-2024 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-june-20-2024

[79] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukrainian-defense-pokrovsk-has-compelled-russia-change-its-approach-eastern-ukraine; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-june-27-2024

[80] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukrainian-defense-pokrovsk-has-compelled-russia-change-its-approach-eastern-ukraine

[81] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukrainian-defense-pokrovsk-has-compelled-russia-change-its-approach-eastern-ukraine

[82] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukrainian-defense-pokrovsk-has-compelled-russia-change-its-approach-eastern-ukraine; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-29-2024

[83] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-31-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-5-2024 ; https://x.com/DefenceHQ/status/1864580705948184870 ;

[84] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-18-2025; https://isw.pub/UkrWar021625

[85] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-13-2025

[86] https://isw.pub/UkrWar021525

[87] https://isw.pub/UkrWar021525

[88] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/how-delays-western-aid-gave-russia-initiative-ukrainian-counteroffensive-kharkiv; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-12-2023; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-15-2023; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-11-2023; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-10-2023; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-6-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-9-2025

[89] https://news.sky.com/story/russias-ability-to-outmatch-ukraine-with-artillery-on-battlefield-significantly-reduced-13267663

[90] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukrainian-defense-pokrovsk-has-compelled-russia-change-its-approach-eastern-ukraine

[91] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukrainian-defense-pokrovsk-has-compelled-russia-change-its-approach-eastern-ukraine

[92] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-march-24-2023

[93] https://isw.pub/UkrWar013125

[94] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-4-2024

[95] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-8-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-9-2024

[96] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-26-2025; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-17-2025

[97] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-26-2025

[98] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-26-2025

[99] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-26-2025

[100] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-26-2025

[101] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukraine%E2%80%99s-kursk-incursion-six-month-assessment; https://isw.pub/UkrWar091424

[102] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukraine%E2%80%99s-kursk-incursion-six-month-assessment; https://isw.pub/UkrWar091424; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-september-6-2024

[103] https://isw.pub/UkrWar082524 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar082224 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-august-18-2024 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-3-2024

[104] https://isw.pub/UkrWar083124; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukraine%E2%80%99s-kursk-incursion-six-month-assessment

[105] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukraine%E2%80%99s-kursk-incursion-six-month-assessment; https://isw.pub/UkrWar082524 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar082224 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar082024 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar082624 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar083124 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar091224 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-august-11-2024; https://isw.pub/UkrWar091124 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-august-22-2024

[106] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukraine%E2%80%99s-kursk-incursion-six-month-assessment

[107] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukraine%E2%80%99s-kursk-incursion-six-month-assessment

[108] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukraine%E2%80%99s-kursk-incursion-six-month-assessment; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-november-2-2024 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-november-11-2024 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-november-18-2024 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-november-30-2024 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-17-2024 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-29-2024

[109] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukraine%E2%80%99s-kursk-incursion-six-month-assessment

[110] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukraine%E2%80%99s-kursk-incursion-six-month-assessment

[111] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukraine%E2%80%99s-kursk-incursion-six-month-assessment

[112] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-13-2025; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-4-2025

[113] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-july-25-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-november-24-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-july-30-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-7-2025

[114] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-15-2025; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-10-2025; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-5-2025; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-6-2025; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-november-20-2024; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-august-24-2024

[115] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukraine%E2%80%99s-kursk-incursion-six-month-assessment

[116] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russias-weakness-offers-leverage

[117] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russias-weakness-offers-leverage

[118] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russias-weakness-offers-leverage