|

|

Salafi-Jihadi Movement Weekly Update, June 21, 2023

Salafi-Jihadi Movement Weekly Update, June 21, 2023

Authors: Kathryn Tyson, Liam Karr, and Peter Mills

Data Cutoff: June 21, 2023, at 10 a.m.

Key Takeaways:

Iraq and Syria. The Iraq and Syria section is on pause until the Salafi-Jihadi Movement Weekly Update, June 28, 2023.

Mali. The Malian junta requested the UN to end its peacekeeping mission in Mali, which is very likely to enable Salafi-jihadi groups to expand and pose greater domestic and transnational threats. The withdrawal of the UN mission will very likely end reconciliation efforts between the Malian government and non-jihadist former rebel groups with ties to al Qaeda–linked militants in Mali. The al Qaeda–linked group in Mali will very likely use these ties and the resulting security vacuum to assert itself as the primary power broker across northern Mali, which it can then leverage to carry out more-sophisticated attacks in central and southern Mali and spread its insurgency to neighboring states in West Africa. The UN withdrawal will also very likely embolden the regional IS affiliate to establish territorial control in northeastern Mali, increasing the group’s threat to US personnel and interests in West Africa.

Somalia. Clan-based disputes between regional and state governments are derailing Somali-led counterinsurgency offensives in central and southern Somalia. These disputes are not isolated, and clan infighting will undermine Somali security to a greater extent and present additional openings for al Shabaab to exploit as the Somali Federal Government (SFG) prepares to assume sole responsibility for Somali security by the end of 2024.

Pakistan. The Tehreek-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP) is expanding and formalizing de facto control over terrain in Balochistan and Punjab provinces, Pakistan, which may enable TTP shadow governors to expand the group’s administrative influence in those areas. The creation of these new governorates outside of TTP’s traditional support areas shows the TTP has become more emboldened in its governance efforts since it ended a cease-fire with the Pakistani government in November 2022.

Afghanistan. The Taliban government’s relocation of TTP militants into northern Afghanistan will exacerbate tensions with locals and provide openings for opposition groups. This transfer of TTP militants will not diminish the security threat Pakistan faces from the TTP.

Assessments:

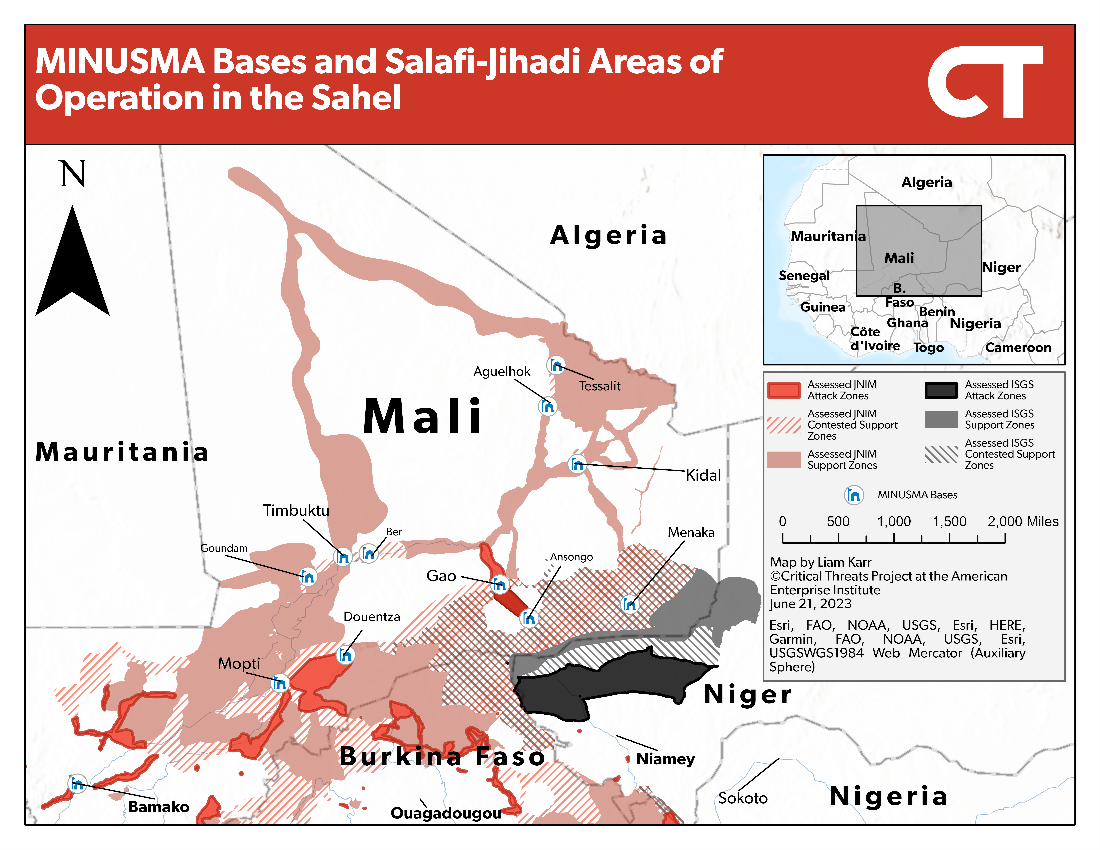

Mali. The Malian junta requested the UN to end its peacekeeping mission in Mali, which is very likely to enable Salafi-jihadi groups to expand and pose greater domestic and transnational threats. On June 16, the junta asked the UN to withdraw the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) “without delay.”[1] Relations between the junta and the West have deteriorated since the junta seized power in 2021.[2] These tensions contributed to France’s withdrawal from Mali and the arrival of Kremlin-linked Wagner mercenaries in late 2021 as an alternative to Western security assistance.[3] The junta also put growing restrictions on MINUSMA that severely hampered its ability to fulfill its mandate and decreased international support for the mission, which CTP assessed in February 2023 would cause MINUSMA’s withdrawal.[4] The Burkinabe government requested that MINUSMA withdraw its troops following the Malian junta’s announcement, but other stakeholders and MINUSMA have not announced withdrawal plans.[5]

MINUSMA’s withdrawal will very likely end reconciliation efforts between the Malian government and non-jihadist groups with ties to al Qaeda–linked militants in northern Mali. Several separatist groups initially fought alongside the al Qaeda–linked militants that now compose JNIM in northern Mali until the French-led international intervention split them away in 2013 and negotiated the peace deal.[6] The Malian government and northern groups have never fully bought into the agreement, which has inhibited the implementation of the deal.[7] MINUSMA has been crucial in facilitating reconciliation and implementation efforts between the Malian government and these armed groups as part of a 2015 peace deal.[8] The separatist groups warned against recalling MINUSMA after the government’s announcement and said that the end of MINUSMA’s support would be a “fatal blow” to the peace deal.[9]

MINUSMA’s withdrawal would present an opening for JNIM to exert greater control over northern Mali and very likely establish itself as the primary power broker and security partner to northern groups. JNIM would be able to expand influence deeper into urban centers without MINUSMA protecting cities and securing key transportation routes.[10] JNIM has demonstrated its willingness and ability to do so. The group has taken advantage of deteriorating security in the northern areas. JNIM cultivated ties with northern groups by presenting itself as a local protector against the Islamic State Sahel Province (ISGS) as ISGS pushed into northeastern Mali.[11] Pro-separatist groups have further warned that without MINUSMA, there are no “credible alternatives” to face security challenges. The Malian government did not pose a barrier to JNIM as it grew its influence because the junta has never given priority to northern Mali and has an antagonistic relationship with local leaders there.[12] The Malian government also lacks the capacity to assert control over the northern area because it is preoccupied with JNIM attacks in central and southern Mali.[13]

Figure 1. MINUSMA Bases and Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation in the Sahel

Source: Liam Karr.

The expansion of JNIM support zones in northern Mali likely would facilitate more-sophisticated JNIM attacks in central and southern Mali. JNIM is using northern Mali as a testing ground for more-sophisticated capabilities, such as armored vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIED) and in-battle drone reconnaissance.[14] The group has demonstrated it seeks to expand its operations in central and southern Mali, where it has carried out several complex VBIED attacks since 2022.[15] The group will also increase its financial revenue through indirect agreements in urban areas and controlling trade routes around urban centers that MINUSMA formerly secured. Greater funding will support JNIM’s operations, including in central and southern Mali.

JNIM will also likely use strengthened havens in northern Mali to support expanding al Qaeda’s insurgency in neighboring states, such as those in the Gulf of Guinea, coastal West Africa, and North Africa. JNIM already has havens and carries out attacks in the northern regions of the Gulf of Guinea.[16] The group is also increasingly active in western Mali, where transnational smuggling routes run into neighboring countries where the group has historically carried out attacks.[17] JNIM is also an affiliate of al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and has incorporated AQIM elements, which gives the group more interest in capitalizing on any potential openings in North Africa.[18]

JNIM could use havens in northern Mali for transnational attacks against the West years after consolidating control in the area. The AQIM emir asserted that JNIM is not preparing external attacks outside of the Sahel in early March 2023.[19] A JNIM shadow governor contradicted this weeks later, however, by threatening to attack any country that fought alongside French and Malian forces, explicitly mentioning the defunct European-led Task Force Takuba and MINUSMA.[20] AQIM and JNIM still aspire to have transnational attack capabilities but are primarily focused on encouraging rather than conducting such attacks to avoid unwanted Western intervention.[21] Past patterns also show that Salafi-jihadi groups can rapidly pivot from local to transnational aims and that numerous factors push local groups to pursue or support transnational attacks.[22]

MINUSMA’s withdrawal would also very likely embolden ISGS to establish territorial control in northeastern Mali, increasing the group’s threat to US personnel and interests in West Africa. ISGS aims to establish a territorial caliphate, and expanding into northeastern Mali would advance this goal.[23] MINUSMA has three bases in major population centers that ISGS already threatens.[24] ISGS has shown it can overrun Malian army bases in these areas, and the MINUSMA withdrawal will make these towns even more vulnerable.[25] ISGS would use new support zones and territorial control in northeastern Mali to grow its resources, attract foreign fighters, and establish attack cells, which would increase its regional threat to US personnel and interests across West Africa.[26]

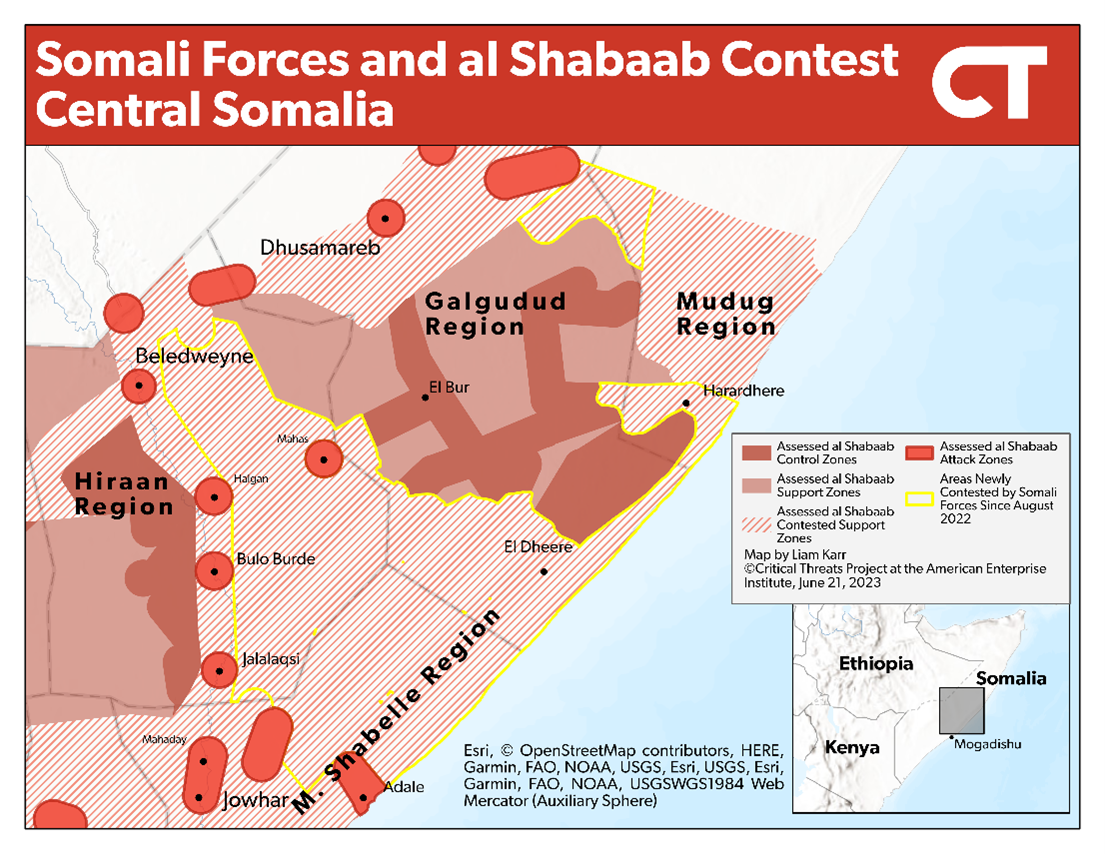

Somalia. A clan-based political standoff in central Somalia will likely distract security forces from holding newly liberated areas and allow al Shabaab to undo some of the gains Somali forces have made since 2022. The Hirshabelle State president sacked the Hiraan regional governor on June 17.[27] The Hiraan regional governor rejected the move and seized the regional capital to establish an independent federal member state, which sets conditions for potential clan violence.[28] Clan militia have been crucial to Somali counterinsurgency operations in central Somalia since operations began in Hiraan in August 2022 and have served as the main holding forces in liberated areas.[29] Clan infighting would, therefore, create gaps for al Shabaab to exploit. Hirshabelle State’s two regions—Hiraan and Middle Shabelle—are each dominated by rival clans that have increasingly clashed over a power-sharing dispute since the current Hirshabelle State president took office in 2020.[30] Somalia lacks clear command and control and coordination measures between state and federal forces, which leads security forces from rival clans to clash over political disputes. This inhibits Somali forces from effectively combating al Shabaab.

Figure 2. Somali Forces and al Shabaab Contest Central Somalia

Source: Liam Karr.

Long-standing clan-based tensions between state and regional governments in southern Somalia hinder the SFG coalition-building efforts for a southern Somalia offensive. The Jubbaland State government and Gedo regional government have been at odds since the Jubbaland State president won a controversial reelection in 2019.[31] The federal government installed a regional administration to undermine the state administration in response in 2020.[32] These fissures align with preexisting clan rivalries between the majority clans in the Gedo and Lower Jubba regions.[33] The Jubbaland State president has refused to empower clan militias in southern Somalia, despite their success in central Somalia.[34] Ethiopia and Kenya have also backed opposite political sides, which will complicate the SFG’s plans to deploy Ethiopian and Kenyan forces in Jubbaland State as part of the offensive.[35] The Jubbaland State president blamed the Gedo administration for delaying the offensive by preventing neighboring-country troops from entering Somalia.[36]

The disputes in Hirshabelle and Jubbaland are not isolated. Clan-based clashes involving Somali security forces have killed dozens of people in South-West State.[37] Somali units are dominated by clan allegiances and function much like clan militia when political tensions rise.[38] The lack of clear command and control and coordination measures between state and federal forces exacerbates these rival loyalties by failing to insulate security institutions from clan politics.[39] This phenomenon also causes Somali politicians to utilize security units as political entities, sometimes undersupplying forces composed of rival clansmen or deploying units for political purposes.[40] All these factors prevent security forces from focusing on combating al Shabaab.

Clan infighting is likely to undermine Somali security and present additional openings for al Shabaab to exploit as the SFG prepares to assume sole responsibility for Somali security by the end of 2024. The African Union mission is withdrawing 2,000 soldiers by the end of June 2023 and plans to withdraw its remaining forces by the end of 2024.[41] African Union forces have functioned as a backstop when Somali forces are preoccupied by clan-based conflict.[42] The SFG has also lobbied to lift the UN arms embargo on Somalia so it can adequately supply Somali forces, but unrestricted weapons flows could inadvertently increase clan conflict and make clan conflicts more deadly.[43]

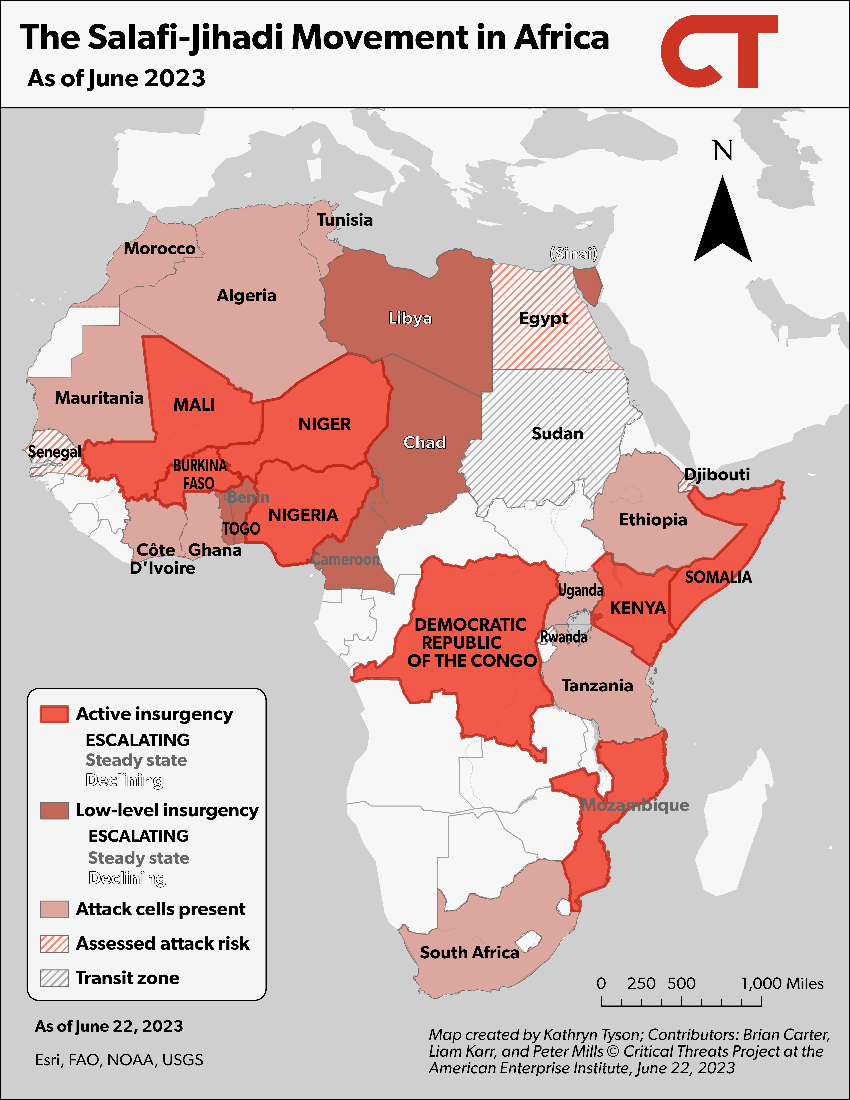

Figure 3. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

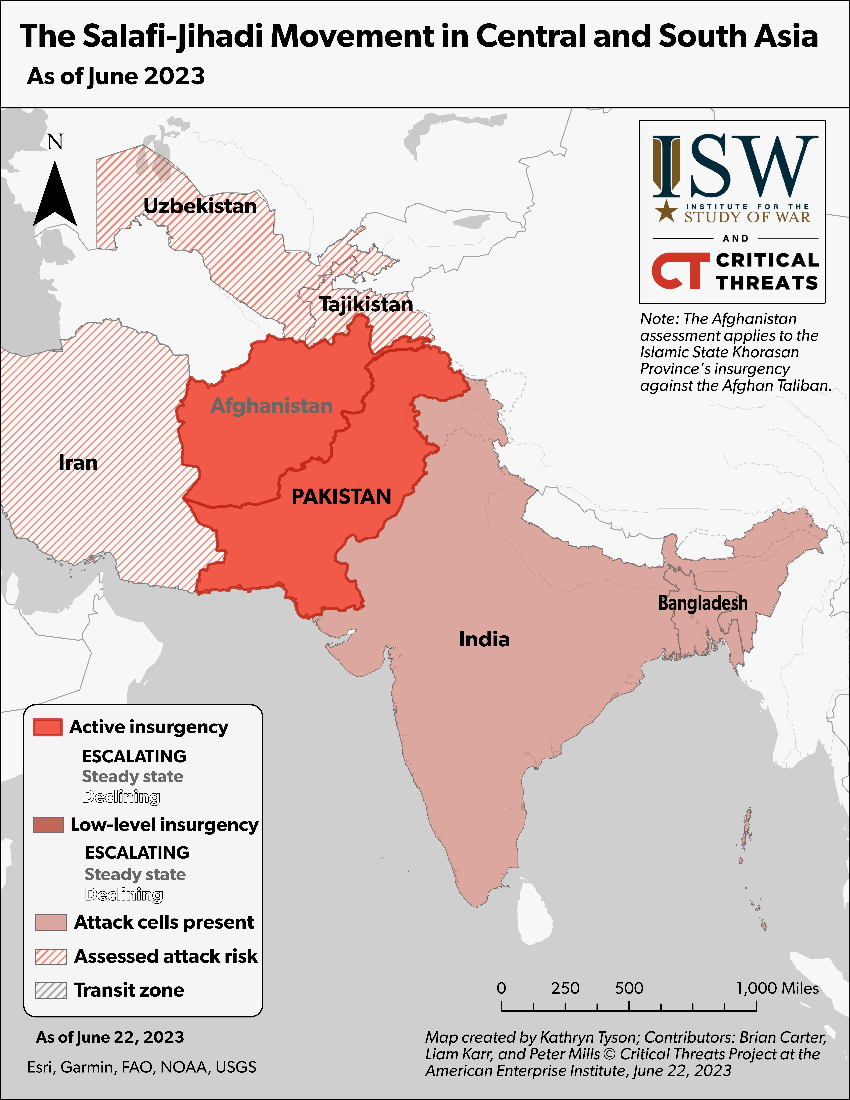

Pakistan. The TTP is expanding and formalizing de facto control over terrain in Pakistan’s Balochistan and Punjab provinces, which may enable TTP shadow governors to expand the group’s administrative influence in those areas. The TTP announced two governorates with shadow governors for the first time in Punjab in eastern Pakistan on June 15. The governorates divide Punjab into “northern” and “southern” regions.[44] The TTP also announced a new governorate and shadow governor in Balochistan in southern Pakistan on June 14.[45] The governorate covers areas in central and southern Balochistan.

Indicators of the TTP successfully expanding governance in these new areas include tax collection and health, justice, and financial services. TTP established tax collection in its shadow governorates in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in northwestern Pakistan.[46] The TTP models its governorates off the Afghan Taliban model, which set up a system of parallel governance to influence the provision of services—such as health, justice, and finance—before the Taliban came to power in Afghanistan in 2021.[47] TTP shadow governors have appeared in the group’s propaganda and have released their own propaganda with the aim of inciting attacks and encouraging Pakistanis to join the group, which suggests they will also help recruit new fighters.[48]

The creation of these new governorates outside of TTP’s traditional support areas shows the TTP has become more emboldened in its governance efforts since it ended a cease-fire with the Pakistani government in November 2022. The TTP primarily draws its fighters from Pashtun areas in Afghanistan and Pakistan.[49] Punjab and Balochistan are non-Pashtun areas far outside established TTP attack zones. The TTP began increasing these governance efforts before November 2022 and has escalated these efforts since. The TTP announced new regional appointments for TTP leaders in February 2022.[50] The group also expanded this structure and appointed ministers for new TTP ministries in December 2022, including ministries for politics, judicial affairs, and education.[51]

Afghanistan. The Taliban government spokesman stated on June 13 that the Taliban planned to relocate an unspecified number of TTP militants from the border with Pakistan to northern Afghanistan.[52] Local sources conflict as to whether the people moving to northern Afghanistan are TTP militants or Pashtun migrants.[53] Local sources also present conflicting accounts of the Taliban’s intent for moving TTP militants from the border area. A regional media outlet reported that the Taliban government plans to move TTP militants to northern Afghanistan to counter an anti-Taliban opposition group: the National Resistance Front (NRF).[54] An Afghan journalist reported the Taliban army is rotating Taliban units in the area, some of whom include TTP elements.[55]

The Taliban moving groups—whether TTP or Pashtun migrants—to northern Afghanistan is likely to alienate local communities and provide the NRF with opportunities to expand its support networks. The Taliban government has previously failed to manage the outbreak of ethnic local tensions, regardless of whether these people are affiliated with the TTP.[56] Afghan media and journalists reported Pashtun immigrants clashed with Uzbek and Tajik locals in northern Takhar Province, in northern Afghanistan, on June 20.[57] NRF rhetoric expressed solidarity with local community leaders angered by the arrival of foreign militants and framed these foreign militants as a direct security threat to Tajikistan, which offers safe haven to the NRF.[58]

Relocating TTP militants from the border areas to northern Afghanistan would be unlikely to reduce the threat the TTP poses to Pakistan. The movement of small groups of TTP fighters, such as the estimated 300 people involved in the dispute in Takhar, will not substantively affect the 7,000–10,000 TTP fighters that Pakistan estimates are in Afghanistan.[59] These small transfers would allow the TTP to retain its bases and safe havens along the border with Pakistan. TTP units based in northern Afghanistan would also still be able to travel to these staging areas near the border and conduct attacks inside Pakistan, as they retain freedom of movement in Afghanistan.[60]

Figure 4. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Central and South Asia

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

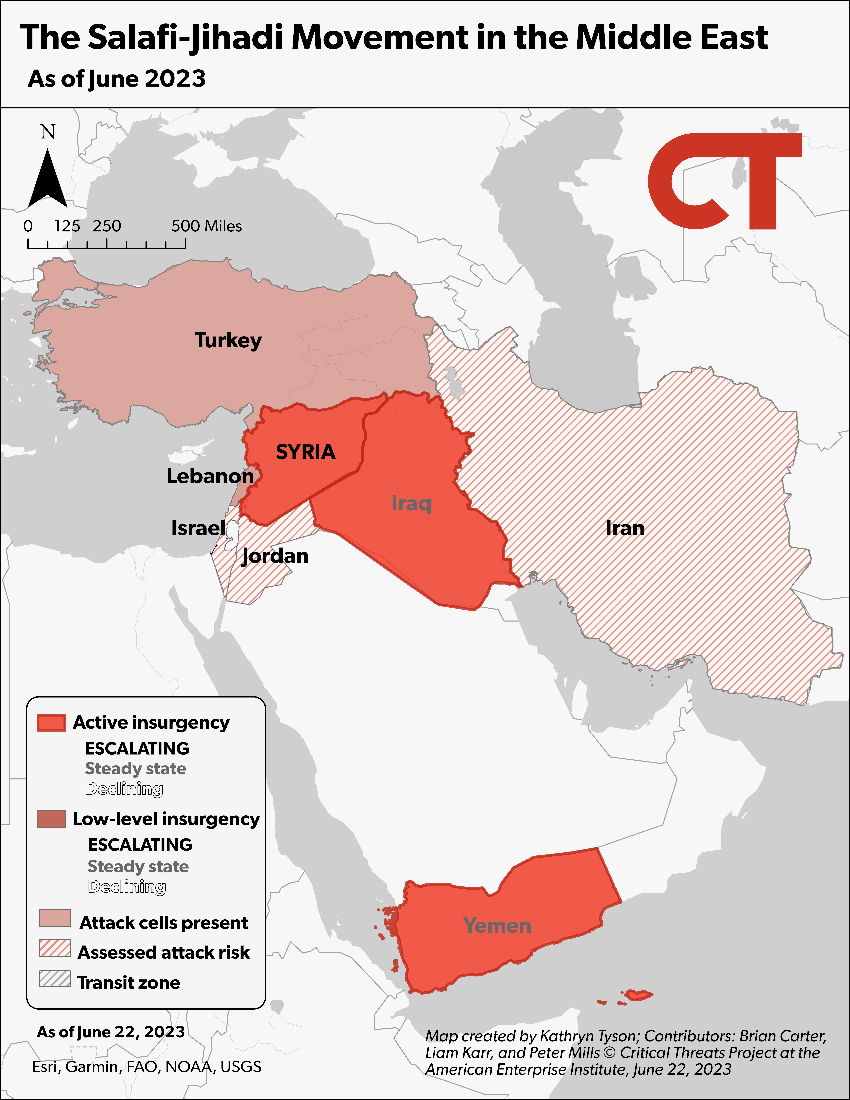

Figure 5. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in the Middle East

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

[1] https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/mali-asks-united-nations-withdraw-peacekeeping-force-minusma-foreign-minister-2023-06-16

[2] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-february-1-2023; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-february-8-2023

[3] https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/africa-file/africa-file-burkina-faso-coup-signals-deepening-governance-and-security-crisis-in-the-sahel; https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/africa-file/africa-file-rapid-french-withdrawal-unravels-counterterrorism-posture-in-mali; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-january-25-2023

[4] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-february-1-2023

[5] https://apanews dot net/2023/06/19/burkina-set-to-withdraw-its-troops-from-minusma

[6] https://jamestown.org/program/anarchy-azawad-guide-non-state-armed-groups-northern-mali

[7] https://www.csis.org/analysis/why-mali-needs-new-peace-deal

[8] https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/mali/minusma-crossroads

[9] https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/mali-faces-spectre-anarchy-after-demanding-uns-departure-2023-06-18

[10] https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/mali/minusma-crossroads

[11] https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/africa-file/africa-file-al-qaeda-linked-militants-take-control-in-northern-mali

[12] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-april-27-2023

[13] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-april-27-2023

[14] https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/africa-file/africa-file-al-qaeda-linked-militants-take-control-in-northern-mali

[15] https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/africa-file/africa-file-al-qaeda-linked-militants-take-control-in-northern-mali; https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20230422-suspected-jihadists-attack-russian-military-camp-in-mali

[16] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-february-22-2023; https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/africa-file/africa-file-salafi-jihadi-groups-may-exploit-local-grievances-to-expand-in-west-africas-gulf-of-guinea; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-june-7-2023#Burkina20230607

[17] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-may-24-2023#Mali20230524; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/al-qaedas-growing-threat-to-senegal

[18] https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/africa-file/africa-file-al-qaeda-linked-militants-take-control-in-northern-mali

[19] https://www.france24.com/en/middle-east/20230306-al-qaeda-leader-in-north-africa-grants-exclusive-interview-to-france-24

[20] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-march-29-2023

[21] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-march-8-2023

[22] https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/the-underestimated-insurgency-continued-salafi-jihadi-capabilities-and-opportunities-in-africa

[23] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-april-19-2023#Sahel20230419

[24] https://reliefweb.int/map/mali/mali-minusma-deployment-may-2023

[25] https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/africa-file/africa-file-burkina-faso-coup-signals-deepening-governance-and-security-crisis-in-the-sahel

[26] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-april-19-2023#Sahel20230419

[27] https://twitter.com/HarunMaruf/status/1670208179140022274?s=20

[28] https://twitter.com/ShabelleMedia/status/1670437915447394305?s=20; https://twitter.com/HussienM12/status/1670427143191265283?s=20

[29] https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/africa-file/africa-file-clan-uprising-bolsters-anti-al-shabaab-offensive-in-central-somalia; https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/somalia/b187-sustaining-gains-somalias-offensive-against-al-shabaab

[30] https://www.hiiraan dot com/news4/2020/Nov/180810/tension_in_hiiraan_as_faction_masses_forces_against_new_hirshabelle_government.aspx; https://puntlandpost.net/2022/01/25/ciidamo-hubaysan-oo-qabsaday-xaafado-ka-tirsan-beledweyne

[31] https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/somalia/b158-ending-dangerous-standoff-southern-somalia

[32] https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/somalia/b158-ending-dangerous-standoff-southern-somalia; http://www.heritageinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Somalia-Averting-Electoral-Violence-in-Somalia-.pdf

[33] https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/somalia/b158-ending-dangerous-standoff-southern-somalia

[34] https://www.garoweonline.com/en/news/somalia/somalia-jubaland-rejects-use-of-clan-militia-in-al-shabaab-war

[35] https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/somalia/b158-ending-dangerous-standoff-southern-somalia; https://www.voanews.com/a/somalia-s-neighbors-to-send-additional-troops-to-fight-al-shabab-/6986748.html

[36] https://twitter.com/GaroweOnline/status/1670903430947241993?s=20

[37] https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/armed-factions-somalias-puntland-agree-ceasefire-after-deadly-clashes-2023-06-21; https://horseedmedia dot net/somalia-10-killed-as-fighting-between-disciplined-forces-intensifies-in-barawe-town-379848

[38] https://www.academia.edu/38914771/The_Somali_National_Army_an_assessment; http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/110878

[39] https://riftvalley.net/sites/default/files/publication-documents/SDP%E2%80%A6Policy%E2%80%A6NationalSecurity%E2%80%94EN%E2%80%94A01_0.pdf

[40] https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/somalia/b176-reforming-au-mission-somalia; https://www.academia.edu/38914771/The_Somali_National_Army_an_assessment

[41] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-june-14-2023#SOM20230614

[42] https://www.ipinst.org/2019/04/transitioning-to-national-forces-in-somalia

[43] https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/whatsinblue/2023/06/somalia-briefing-and-consultations-9.php; https://hiraalinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Somali-Arms-Embargo.pdf

[44] https://twitter.com/khorasandiary/status/1669368108526735361

[45] https://twitter.com/KhyberScoop/status/1668856407368794113

[46] https://twitter.com/khorasandiary/status/1617766519764832256

[47] https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2018/06/21/the-taliban-has-successfully-built-a-parallel-state-in-many-parts-of-afghanistan-report-says; https://ctc.westpoint.edu/the-tehrik-i-taliban-pakistan-after-the-talibans-afghanistan-takeover

[48] https://twitter.com/khorasandiary/status/1656686487608369159; https://twitter.com/KhyberScoop/status/1631030660902305793

[49] https://ctc.westpoint.edu/the-revival-of-the-pakistani-taliban

[50] https://twitter.com/ihsantipu/status/1496167694353190915?s=21

[51] https://twitter.com/khorasandiary/status/1608885785985683457

[52] https://www.bbc.com/persian/articles/cll0mg29y41o

[53] https://twitter.com/OBarzgar/status/1671138375842119680; https://twitter.com/Payam__Azadi/status/1671110800361025541; https://twitter.com/SamiYousafzaii/status/1671412616051277831

[54] https://thekhorasandiary dot com/2023/06/17/post-cease-fire-relocation-of-pakistani-taliban-in-afghanistan-spurs-new-hope-for-fragile-regional-peace; https://twitter.com/i/web/status/1671398430663659521

[55] https://twitter.com/TajudenSoroush/status/1671219653467578368?s=20

[56] https://twitter.com/Payam__Azadi/status/1569729415310868480; https://twitter.com/aamajnews_24/status/1569750303167356928; https://8am dot af/nomadic-attack-on-the-houses-of-takhar-natives-four-people-were-injured

[57] https://twitter.com/Mukhtarwafayee/status/1671101943630921729; https://8am dot media/eng/local-residents-engaged-in-tense-battle-against-nomadic-intruders-in-khaja-bahauddin-takhar-province; https://www dot afintl dot com/202306205964

[58] https://twitter.com/alinazary/status/1671398430663659521; https://twitter.com/NRFafg/status/1671784605689565184

[59] https://newlinesinstitute.org/pakistan/with-no-help-from-kabul-pakistan-faces-the-ttp-threat

[60] https://www.mei.edu/publications/pakistan-afghan-taliban-relations-face-mounting-challenges