|

|

Syria Update: Regime Breaks Siege of Wadi al-Deif

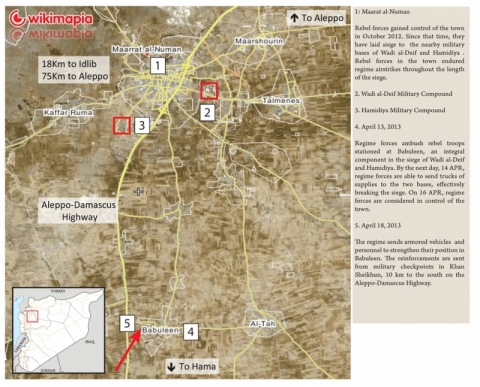

On April 14, 2013, regime forces broke the 6-month siege of the Wadi al-Deif and Hamidiya military compounds outside of Maarat al-Numan, putting the rebel opposition in the area on the defensive and reestablishing overland supply lines to the bases.[i] The regime is now able to redistribute its military forces in the north, particularly its airpower which was tied up running dangerous supply drops to the troops besieged in the two bases, and engage the opposition for control of the Aleppo-Damascus highway. Although this new development will impact military operations in the northern provinces for both sides, it also highlights the military deficiencies that exist among the opposition groups and the continued capabilities of the regime. Although the regime has given up territory to the opposition, it has largely done so by choice to consolidate forces in more strategic locations, and it retains the ability to seize the strategic advantage when the opportunity presents itself.

Wadi al-Deif and Hamidiya have been the last bastions of regime power in Maarat al-Numan since the city fell in October 2012.[ii] Under siege since then, regime forces have repelled a series of increasingly coordinated attacks as rebel groups throughout Idlib province have attempted to consolidate their control over the area. These combined efforts, which forced the regime to rely on airdrops of equipment and supplies, were organized by Jabhat Nusra, who provided cohesion and leadership to the various brigades gathered by the Idlib Military Council.[iii] However, tension between the local battalions and larger independent brigades, the departure of Jabhat Nusra and its allies to fight in al-Raqqa and Hasaka province, and lack of supplies degraded the military capacity of the rebel groups and the effectiveness of their siege, and allowed the regime to outflank their position.[iv]

Click map to enlarge.

Breaking the siege of Wadi al-Deif and Hamidiya has created two significant opportunities for the regime. In Idlib and Aleppo province the regime has been forced to cede rural territory and military installations due to manpower and resource constraints. As a result, regime ground forces have concentrated on holding Aleppo and Idlib city while its air force has been used to supply bases under siege, harass the rebel opposition, and attack urban centers.[v] Supply lines to the embattled forces at Wadi al-Deif and Hamidiya have been reestablished, such that six trucks filled with weapons were seen entering the two bases the same day the siege was broken. The regime can now make a viable effort to retake Maarat al-Numan and the positions it has lost along the Aleppo-Damascus highway and potentially connect its ground line of communications with its forces in Aleppo.[vi]

Perhaps more importantly, the regime is now able to reassign the air power it was using to supply Wadi al-Deif and Hamidiya. With sorties no longer needed to sustain the forces tied up by the opposition in these two bases, the regime can choose to fly missions against the opposition elsewhere in Syria or resupply other military bases under siege in Aleppo. Rebel ground-to-air capabilities have increased throughout the conflict, threatening the regime’s comparative advantage. This has made the supply runs to these two bases increasingly dangerous; a helicopter supplying Wadi al-Deif was shot down as recently as April 11, 2013.[vii] The regime has relied on its air superiority to deny territory to the opposition and blunt their offensives, and the ability to protect these assets will be a major contributing factor to their ability to prolong the civil war and keep rebel gains to a minimum.

In some respects, the events at Wadi al-Deif represent a microcosm of the broader Syrian conflict. They can clarify the capabilities of the regime and the opposition, and illustrate how future campaigns may look. The rebel opposition experienced its greatest success during the siege when it was able to bring to bear a larger number of forces than the regime, comprised of units from more disciplined groups that helped provide organizational support and cohesion to the campaign. Once Jabhat Nusra and some of these franchised brigades left to fight in Aleppo, al-Raqqa, and Hasaka, the remaining rebel battalions lacked the capability to contain the regime. Although the opposition has proven it has the ability to seize territory from the regime, its fighting prowess should not be overestimated; these gains are partly a result of the regime’s decision to position its remaining forces in strategic military and urban centers and allow rebels control over much of the countryside. If rebel units are diverted from one front, or stretched too thin, the regime retains the capacity to counterattack, such as it has recently done in Deraa, Damascus, Aleppo, and now Wadi al-Deif.[viii]

Despite the efforts of the opposition, the regime was able to rely on its air superiority to keep its forces in Wadi al-Deif and Hamidiya supplied well enough to retain control of the facilities and bombard the surrounding area with indirect fire. Furthermore, the regime was able to launch airstrikes against Maarat al-Numan consistently while engaging the opposition throughout Syria. The regime’s reliance on the air force to compensate for troop numbers and force projection, maintain the upper hand in the overall conflict, and limit the gains of the opposition should not be underestimated. The case of Maarat al-Numan is thus an excellent example of the continued importance of the regime’s air capacity.

At this point, the struggle for Maarat al-Numan and the immediate vicinity along the Aleppo-Damascus road continues. The regime has moved equipment and personnel from regime checkpoints 10km south in Khan Sheikhun into Babuleen to secure supply lines to Wadi al-Deif, while the opposition has been working to contain their advances.[ix] With the advantages afforded to the regime through their air superiority, they may choose to press their advantage and make the push to Aleppo once the Maarat al-Numan area is secure. However, this would likely mean diverting troops from a different front. The same conundrum exists for the opposition, who could choose to reinforce the area in the attempt to retake lost territory and isolate the two military bases again, but at the cost to another front elsewhere in the country. With each side looking towards the endgame, troop disposition at the operational level of war is paramount and how strategic capabilities are used becomes more and more important.

[i] Hania Mourtada and Rick Gladstone, “Assad’s Forces Break Through Rebel Blockade of Military Bases,” New York Times, April 15, 2013.

[ii] “Even as rebels capture key cities, their drive through northern Syria slows as ammo and supplies run low,” The Associated Press, March 5, 2013.

[iii] Elizabeth O’Bagy, “The Free Syrian Army,” Institute for the Study of War, March 2013.

[iv] Erika Solomon, “Assad’s forces break rebel blockade in north Syria,” Reuters, April 15, 2013.

[v] Joseph Holliday, “The Assad Regime: From Counterinsurgency to Civil War,” Institute for the Study of War, March 2013

[vi] Syrian Observatory for Human Rights Facebook page, April 15, 2015, https://www.facebook.com/syriaohr

[vii] Syrian Observatory for Human Rights Facebook page, April 11, 2015, https://www.facebook.com/syriaohr; “Process of a helicopter dropping,” YouTube, Published on April 11, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nSasBHOxSlk

[viii] Hania Mourtada, “Syrian Forces Push Back at Rebel Positions, New York Times, April 7, 2013; Erika Solomon, “At least 45 die in shelling, executions in Syrian town: activists,” Reuters, April 11, 2013; Oliver Holmes and Mariam Karouny, “Suicide car bomber kills 15 in central Damascus, Reuters, April 8, 2013 .

[ix] Erika Solomon, “Rebels push Assad’s army away from vital north Syria highway,” Reuters, April 16, 2013; Syrian Observatory for Human Rights Facebook page, April 18, 2013, https://www.facebook.com/syriaohr.