|

|

Nord Stream 2 Poses a Long-Term National Security Challenge for the US and Its Allies

By Nataliya Bugayova with Frederick Kagan

Key Takeaway:

Russian President Vladimir Putin is pressuring Ukraine and the West on multiple fronts. He has set conditions to conduct military operations against Ukraine on a large scale. He is exploiting Russia’s leverage on Europe’s energy supplies and enabling Belarusian escalation against Poland, a NATO country. These efforts are parts of a deliberate campaign supporting specific demands Putin is making of the West, including permanently abjuring further enlargement of NATO and military support to Ukraine. He may not launch the invasion he has prepared, but he is determined to use its threat along with his other tools of leverage to compel the West’s formal recognition of Russia’s suzerainty over the former Soviet states. Nord Stream 2 is part of these efforts and always has been. It is a threat to Europe’s security and to Ukraine’s independence. This pipeline will change the geopolitical landscape in Europe for years to come. It is worth renewing the fight to prevent Nord Stream 2 from starting operations.

The Nord Stream 2 (NS2) case is also an opportunity to re-examine the widely held but inaccurate belief that Putin has no plan or strategy. The West’s Russia policy has for years ignored Moscow’s tactical advances until they became strategic wins. The West has repeatedly passed by chances to impede Putin’s advances at acceptable costs, recognizing Russia’s gains only when the costs of preventing them have become prohibitively high. The United States could have generated better options to stop NS2 had it recognized the challenge the project posed earlier and focused more on the issue.

The United States waived sanctions on Nord Stream 2 AG—the company responsible for the pipeline’s operation, which is wholly owned by Russia‘s state gas giant, Gazprom—in May 2021.[1] US officials asserted at the time that it was already impossible to stop NS2 and that attempting to do so was not worth the price of damaging the US-German relationship.[2] The pipeline is completed but it still needs to pass European Union (EU) certification. A German regulator temporarily halted the certification process for NS2 on November 16, citing the requirement for Nord Stream 2 AG to form a German subsidiary company.[3] A group of US senators proposed a legislative amendment on November 8 to implement sanctions on NS2.[4]

German arguments in favor of the pipeline downplay the threat NS2 poses to German and European security and the damage it will do to Ukraine. German officials argue that the pipeline will enhance the security of energy supplies to Germany by providing another means of transportation in addition to the pipeline already coming through Ukraine and Belarus.[5] They also see NS2 as a key part of Germany’s efforts to phase out nuclear energy and coal in pursuit of environmental goals and argue that Germany has the right to exercise its independent energy policy.[6]

NS2 is unlikely to enhance the security of energy supplies to Europe, however. Existing pipelines provide sufficient capacity for Russia to supply natural gas to Europe.[7] NS2 will add capacity and redundancy, presumably letting Germany reduce its use of coal, but it was never the only way to accomplish those goals. Had the US, Germany, and the rest of Europe approached the challenges NS2 solves with a coherent policy that weighed NS2’s risks as well as its promise earlier on, Germany and the US would not face the current dilemma.

The German dismissal of NS2’s risks is based in part on accepting the Kremlin’s line that business is business and not part of Putin’s machinations. But NS2 was never simply about business for the Kremlin. Rather, NS2 will allow the Kremlin to bypass Ukraine—potentially eliminating gas transit via Ukraine completely and stripping Europe of a major route. NS2 will also supply Russian gas directly to Germany, further increasing Russia’s energy leverage over the country. Finally, the long-term geostrategic risks of empowering Putin by allowing NS2 discussed below will likely outweigh whatever economic benefits and reliability advantages that Germany assesses it will get from NS2.

The Kremlin continues to use energy as a weapon, and N2S will be no exception. The Kremlin’s information operations have advanced the false narrative that “Russia’s business is just business” far enough that it is important to restate that the Kremlin routinely uses energy policy to pressure other countries.[8]

Putin’s attempt to limit Moldova’s EU integration is a recent example of many. The Kremlin raised gas prices for Moldova in October and threatened to cut off gas supplies. The Kremlin then reportedly offered to reduce gas prices if Moldova amended its free trade agreement with the EU, postponed reforms required for further EU integration, and paid a disputed debt to Gazprom.[9] Russia and Moldova reached a gas deal at the end of October, which Moldova’s President Maia Sandu defended.[10] Moldova paid off the debt on November 26, 2021.[11] The Kremlin, however, indicated that it will continue using Russia’s energy leverage, as Gazprom stated on November 26 it fears future delinquent payments from Moldova.[12]

The Kremlin is using the ongoing energy crisis in Europe to force NS2’s certification. Putin could have increased gas delivery to Europe amid soaring prices through existing infrastructure, but he chose not to.[13] Instead, Putin called on Germany to approve NS2, stating that Russia will use NS2 to “expand supplies” after the pipeline is certified.[14] This approach is energy blackmail, and the West must recognize it as such.

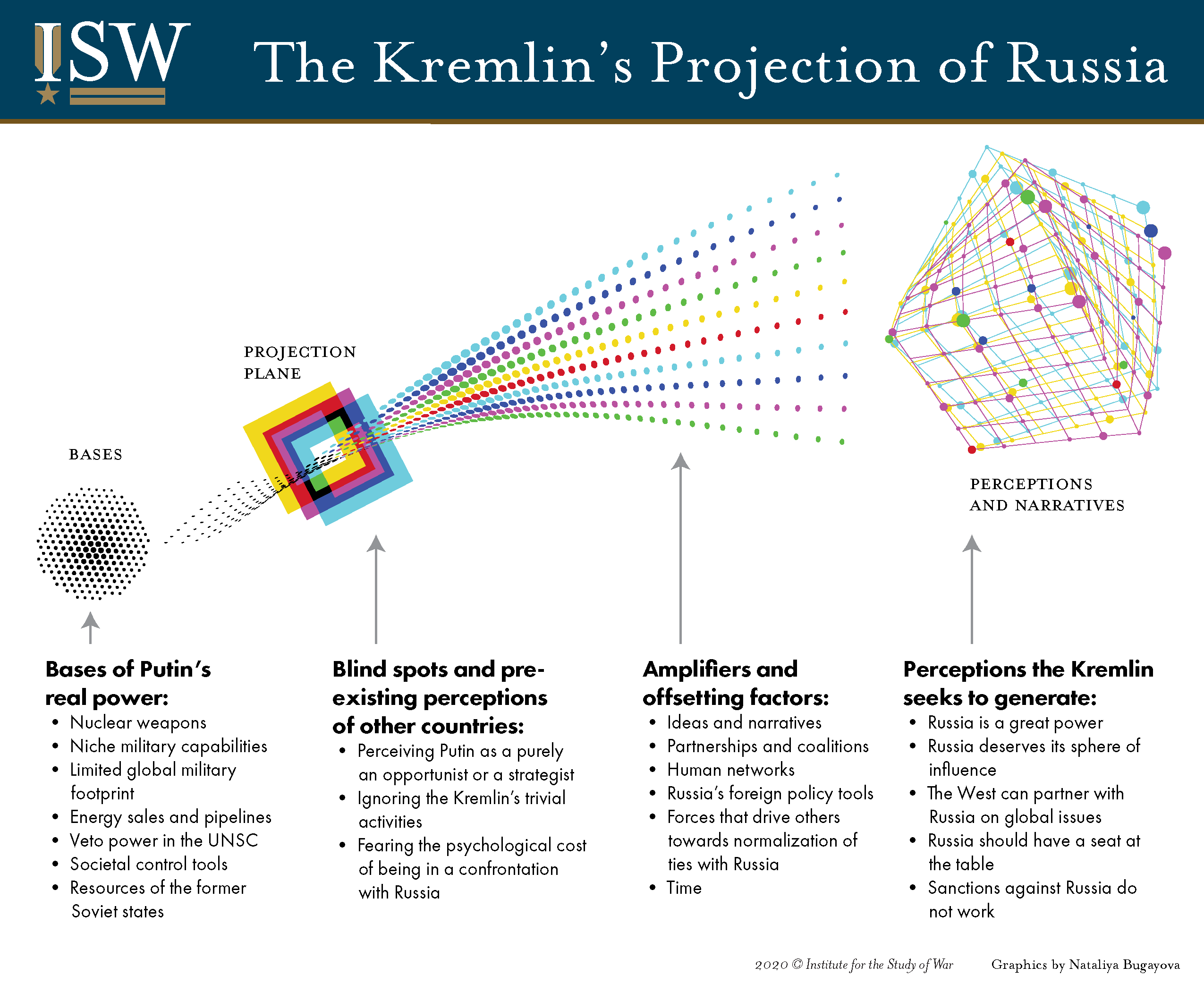

NS2 boosts Putin’s otherwise limited power. Putin has few sources of real power. Energy pipelines are one such source. (See the graphic)

Click here to expand the graphic below.

Boosting a major base of Putin’s otherwise limited power through the tacit endorsement of NS2 is contradictory to the principle of long-term strategic competition with Russia outlined in the US National Defense Strategy.[15]

NS2 is more than an economic and political pressure tool; the pipeline will become another pillar of the Kremlin’s asymmetric power projection.

The Kremlin’s asymmetric approach is based in part on its ability to amplify niche capabilities, such as energy sales, via information operations, human networks, and coalitions.[16]

With Russian pipelines come Russian influence networks. The Kremlin has already established a network of people who are economically dependent on NS2 and therefore have a vested interest in the pipeline’s success, which likely has empowered NS2’s progress.[17] The Kremlin will be able to further expand this network if the pipeline is launched, as more German companies and individuals will become involved in it and dependent on it.

With Russian influence networks come information networks and operations. The Kremlin uses its influence networks to spread Kremlin-friendly narratives. The Kremlin will be able to expand an information ecosystem around NS2 and enhance Russia’s ability to shape perceptions in Europe for years to come. Russian NS2-dependent human and information networks will be hard to weed out once they solidify.

Symbols have growing importance. NS2, if launched, will be a major and lasting symbolic win for the Kremlin. The United States and Germany approached NS2 sanctions discussions without sufficient involvement from Central and Eastern European states; this reinforced the Kremlin’s argument that Central and Eastern European states have truncated sovereignty, one of Putin’s top informational goals.

NS2 is also a potential intelligence tool. The Kremlin might place surveillance capabilities along the pipeline.[18]

The Kremlin will leverage NS2 to drive divisions within and among the United States and its EU/NATO partners—one of Putin’s longstanding objectives.

NS2 has already been a divisive issue within Europe and between the United States and its European partners. European approval of NS2 was not unanimous: Central and Eastern European countries have largely opposed the pipeline.[19] The German rejection of these concerns has increased tensions within NATO.

The Kremlin will continue to leverage the pipeline to drive divisions but with newfound legitimacy and, if NS2 is approved, in perpetuity. NS2 will aid the Kremlin’s efforts to create coalitions with Western European countries at the expense of the agency of Central and Eastern European countries, the EU-US relationship, and NATO cohesion.

NS2 will make both Germany and Europe more vulnerable—not more resilient—US partners, including in the US competition with China.

The Biden Administration’s key expected benefit from waiving sanctions on NS2 is enhancing America’s relationship with a key ally—Germany—an important and valid objective.

This benefit is overstated, however. German political leadership was not unanimous in supporting NS2. The Green Party, which won 15 percent of the vote in recent elections, objected to NS2. The Green Party’s co-leader, Annalena Baerbock, Germany’s next foreign minister, publicly opposed the Kremlin’s energy blackmail and NS2.[20]

NS2 is a clear, visible, and likely permanent increase in Putin’s effective strength and leverage. It is far from clear, however, what concrete advantages the United States has gained from conceding this vital point to Berlin. The Biden Administration would have done better to trade acceptance of NS2 for a German commitment to defend NATO’s eastern flank as well as the independence of Ukraine—if the United States had to accept NS2 at all.

NS2 poses a major risk to Ukraine. NS2 bypasses Ukraine, and its risks to Ukraine have been well discussed.[21] Two additional considerations are worth highlighting.

First, Russia is likely setting up Ukraine for an energy crisis this winter. Gazprom reduced gas transit through Ukraine several times this year.[22] Russia temporarily halted coal supplies to Ukraine in October.[23] Gazprom signed a deal with Hungary that will further limit Russia’s gas transit through Ukraine.[24] Belarus announced it suspended electricity supply to Ukraine starting November 18, though Belarus reportedly resumed the supply on November 21.[25] Ukraine also relies on Belarus for a significant portion of its oil imports, creating additional exposure to the Kremlin’s pressure.[26]

High gas prices are already a source of societal and political tensions in Ukraine. The Kremlin might use this multi-faceted energy pressure, which will be amplified by the launch of NS2, to sow instability in Ukraine.

Second, the NS2 launch will increase the probability of additional Russian military action against Ukraine. Reducing Russia’s dependency on Ukraine for its gas transit reduces Ukraine’s checks on the Kremlin. Putin prioritizes the NS2 pipeline, approval of which would be put at risk by an overt Russian military offensive into Ukraine. That risk largely disappears once the pipeline is certified. Halting NS2 or delaying its certification into the summer months of 2022, when Putin’s energy leverage is diminished, might decrease the chances of an overt Russian invasion of Ukraine, or at least increase the costs of doing so.

The NS2 case is an opportunity to examine blind spots in the United States’ Russia policy.

1. The United States continues to ignore the Kremlin’s tactical activities until they become strategic gains. This blind spot fundamentally stems from the United States viewing Putin as an opportunist.

Putin has, however, repeatedly shown that he is willing to pursue the same goal for years and accept temporary setbacks to advance larger objectives—be it with NS2, Russia’s integration of Belarus, or the establishment of a Russian naval base in Sudan.[27] Putin has invested the time and effort of some of the Kremlin’s most senior officials in NS2 over an extended period, indicating the project’s importance. This exertion should have been an indicator for the United States and Germany early on that NS2 was more than an economic undertaking.

2. The United States continues to misunderstand how the Kremlin’s asymmetries work. Russia amplifies its few limited anchors of power—such as energy sales—with information operations, coalitions, and human networks. NS2 will likely be another perpetual anchor for Russia in the EU and a perpetual information win.

3. The United States continues to compartmentalize Russia’s activities, aiming to confront Russia on some issues while engaging on others. NS2 has always been a geopolitical project focused on gaining additional leverage over the EU and Ukraine. The economic benefits of Russia’s energy projects do matter to Putin, but even they serve to support the overall stability of Putin’s regime.

Putin will exploit this continued compartmentalization. Specifically, Putin will use Washington’s focus on decarbonization to advance Russia’s energy leverage and pitch Russia’s gas and nuclear power. The Kremlin has already been setting information conditions for this play. Putin framed Russia as being a global leader in decarbonization due to Russia’s gas and nuclear power generation in his November 18 speech to Russia’s Foreign Affairs Ministry.[28]

The United States should reject “inevitability” when it comes to Russia. The NS2 completion may or may not have been inevitable at the time President Biden took office. But if it was inevitable, that is because of the long-standing US failure to set conditions with US partners and allies against the Russian challenge.

The United States could have generated better options if its political leaders had settled on a sustained strategy and engaged more closely with US partners in Europe. NS2 should not have become a point of contention between the United States and Germany or a de facto bilateral US-Germany issue.

The United States giving in on NS2 to strengthen ties with Germany, even as part of an effort to pivot NATO to a China focus, is ineffective and counterproductive as it weakens commitments and trust within the alliance. US policy must strengthen the entire NATO commitment to defend itself, including all its members, against the continuing Russian threat. Stopping or delaying NS2 is a good place to start, even now.

[1] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-57180674; https://www.nord-stream2 dot com/company/shareholder-and-financial-investors/#:~:text=Nord%20Stream%202%20AG%20is,LLC%2C%20a%20PJSC%20Gazprom%20subsidiary

[2] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-05-19/u-s-to-waive-new-sanctions-on-nord-stream-2-pipeline-to-germany

[3] https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/german-energy-regulator-suspends-nord-stream-2-certification-makes-demands-2021-11-16/

[4] https://www.foreign.senate.gov/press/ranking/release/risch-leads-colleagues-in-ns2-amendment-to-ndaa

[5] https://www.dw.com/en/german-industry-defends-nord-stream-2-gas-pipeline/a-45611911; https://www.dw.com/en/nord-stream-2-gas-pipeline-what-is-the-controversy-about/a-44677741; https://www.politico.eu/article/vladimir-putin-german-chancellors-nord-stream-russia-energy-angela-merkel/

[6] https://www.dw.com/en/nord-stream-2-gas-pipeline-what-is-the-controversy-about/a-44677741; https://www.politico.eu/article/vladimir-putin-german-chancellors-nord-stream-russia-energy-angela-merkel/;

https://www.upstreamonline.com/production/maas-movement-german-foreign-minister-fires-back-at-us-over-nord-stream-2/2-1-895679

[7] Gazprom Export supplied approximately 175 billion cubic meters of gas to Europe in 2020, according to Gazprom’s website. Russia exports gas to Europe via Ukraine, Belarus, Nord Stream 1 and TurkStream. The combined capacity of these pipelines exceeds Russia’s current export volume. Ukraine’s transit system has capacity of 140-160 billion cubic meters, which Gazprom uses 40 billion cubic meters. Ukraine regularly offers additional capacity to Gazprom. https://www.kyivpost.com/business/russia-refuses-to-book-additional-gas-transit-capacity-in-ukraine.html (Nordstream capacity: https://www.gazprom dot com/projects/nord-stream/; TurkStream capacity: https://www dot gazprom.com/projects/turk-stream/; Gazprom export: http://www.gazpromexport dot ru/en/statistics/; Ukraine transit capacity: https://www.reuters.com/article/ukraine-gas-transit/ukraine-offers-extra-15-mcm-day-of-gas-transit-capacity-for-oct-idINL8N2PQ2HD; Belarus transit capacity: https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/natural-gas/111221-russia-says-to-fulfil-contractual-gas-supply-obligations-amid-belarus-threat

[8]https://www.politico.eu/article/russia-cuts-gas-toukraine/; https://www.reuters.com/article/us-energy-russia-cutoffs/factbox-russian-oil-and-gas-export-interruptionsidUSLS57897220080829

[9] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russia-review-october-20-%E2%80%93-november-9-2021; https://www.ft.com/content/138a0815-98bd-42b8-b895-49e89b980a99?shareType=nongift

[10] https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/moldovas-support-ukraine-did-not-spark-russia-gas-row-president-says-2021-11-19/

[11] (https://tass dot com/economy/1365745; https://tass dot com/economy/1367111; https://www.epravda dot com.ua/news/2021/11/23/680034/; https://seenews dot com/news/moldovagaz-repays-13-bln-lei-74-mln-mln-debt-to-russias-gazprom-763276)

[12] https://tass dot com/economy/1367111; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russia-review-november-10-%E2%80%93-november-30-2021

[13] The gas flows via the portion of the Yamal-Europe pipeline have been on hold in early November.

Gazprom did not book additional capacity to transport gas via Poland and Ukraine. https://ria dot ru/20211109/gaz-1758299538.html; https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-gas-ukraine-gazprom-poland/31541962.html; https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/gas-flows-still-hold-via-russias-pipeline-poland-germany-2021-11-04/#:~:text=Gas%20flows%20still%20on%20hold%20via%20Russia's%20pipeline%20from%20Poland%20to%20Germany,-Reuters&text=MOSCOW%2C%20Nov%204%20(Reuters),Gascade%20operator%20showed%20on%20Thursday.

[14] https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/13/business/energy-environment/putin-nord-stream-germany.html

[15] https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf

[16] P. 25 https://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/Putin's%20Offset%20The%20Kremlin's%20Geopolitical%20Adaptations%20Since%202014.pdf

[17] https://www.nord-stream.com/about-us/our-shareholders-committee/; https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-nordstream-2-lobbying/lobbying-for-russian-pipeline-spikes-in-washington-idUSKCN2500FI; https://www.csis.org/analysis/russian-influence-operations-germany-and-their-effect

[18] https://www.rferl.org/a/us-warns-russian-german-nord-stream-2-pipeline-risks-trigger-sanctions-security-concern-oudkirk/29233548.html

[19] https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/us-european-lawmakers-issue-statement-opposing-nord-stream-2-2021-08-02/

[20] https://www.politico.eu/article/baerbock-against-operating-permit-for-nord-stream-2/; https://www.cleanenergywire.org/news/green-party-leader-criticises-nord-stream-2-deal-undermining-ukraines-security

[21] https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/nord-stream-2-germany-must-listen-to-ukrainian-security-concerns/; https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/security-implications-nord-stream-2-ukraine-poland-and-germany

[22]https://www.reuters.com/article/ukraine-gas/update-1-ukraine-says-russias-gazprom-has-cut-daily-gas-transit-volume-to-60-mcm-idUSL1N2RT15D

[23] https://ria dot ru/20211029/ugol-1756920452.html

[24] https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/ukraine-says-gazprom-suspends-use-its-transit-system-hungary-supplies-2021-10-01/; https://www.rferl.org/a/hungary-ukraine-gazprom-deal-envoy/31481746.html

[25] https://www.epravda.com.ua/rus/news/2021/11/21/679963/

[26] https://www.eurointegration.com.ua/articles/2021/06/3/7123982/

[27] P. 20 https://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/Putin's%20Offset%20The%20Kremlin's%20Geopolitical%20Adaptations%20Since%202014.pdf; For example, the Kremlin discussed establishing a naval supply center on the Red Sea in Sudan in 2018 and continues its attempts up to this day. Russia has been trying to establish an air base in Belarus since at least https://ria dot ru/20190112/1549268157. html.; https://tass dot com/defense/1359587; https://www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-belarus-airbase/russia-complains-over-belaruss-refusal-to-host-air-base-idUSKBN1WB1NT

[28] http://kremlin dot ru/events/president/news/67123; ISW has extensively written about Russia’s most recent efforts to integrate Belarus in Russia’s security and political structures