|

|

Salafi-Jihadi Movement Weekly Update, May 24, 2023

Salafi-Jihadi Movement Weekly Update, May 24, 2023

Authors: Brian Carter, Kathryn Tyson, Liam Karr, and Peter Mills

Data Cutoff: May 24, 2023, at 10 a.m.

Key Takeaways:

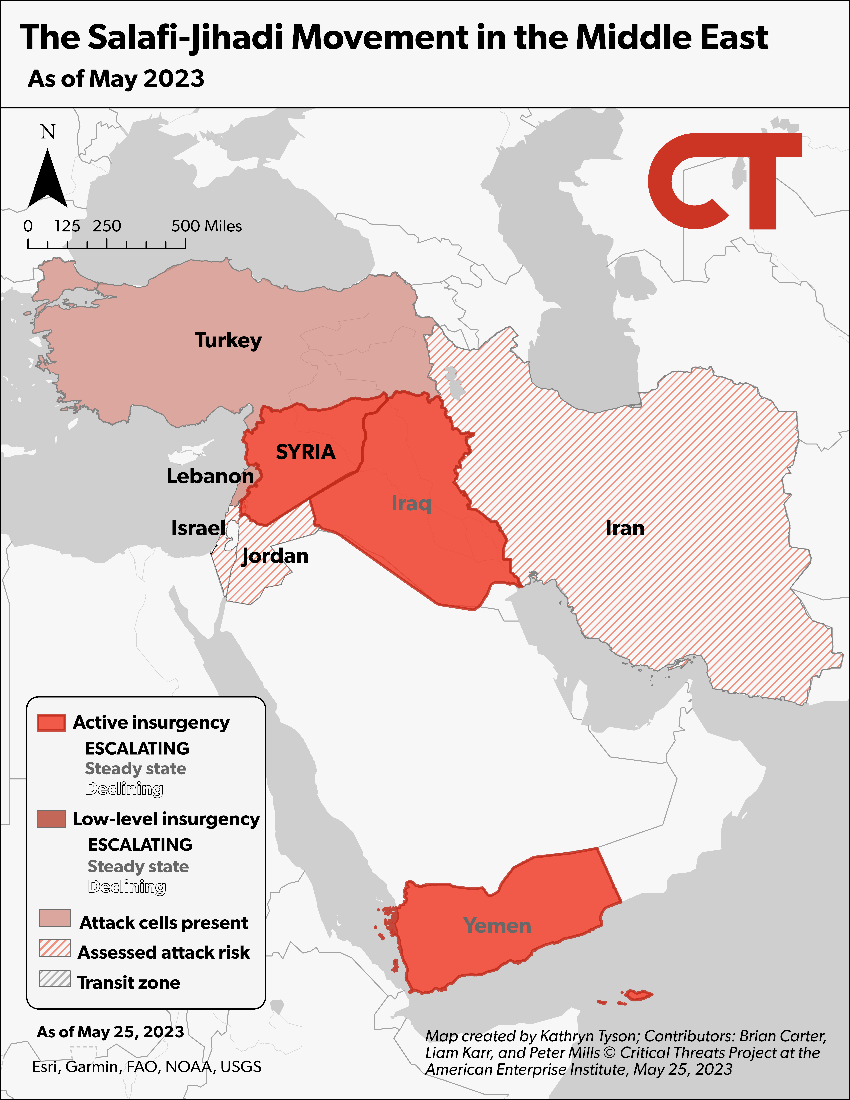

Iraq and Syria. ISIS is attempting to reconstitute itself and rebuild its capabilities in the areas surrounding Baghdad, but it is likely to succeed only north of Baghdad, where local conditions are more advantageous to the group. ISIS can generate local support north of Baghdad by appealing to communities threatened by abuse and harassment from Iranian-backed Iraqi Shi’a militias, which have threatened to commit sectarian cleansing against Sunni communities. ISIS attempts to rebuild its capabilities south of the city are enfeebled by long, third-rate supply lines through unpopulated desert. ISIS cells south of the city also suffer from bad operational security and a lack of local support.

Mali. Al Qaeda-affiliated militants have escalated its rate of attacks in western Mali since late 2022 to increase its revenue and support its campaign to degrade Malian lines of communication around the Malian capital. The militants may be trying to increase its ties with illicit networks in western Mali to strengthen its position in the area, which could create opportunities to spread its insurgency to neighboring countries in the future.

Somalia. Somali-US drone strikes targeting al Shabaab leadership may temporarily weaken the group’s capabilities but will not disrupt al Shabaab’s regional threat. The al Shabaab network will continue organizing regional attacks from its havens in southern Somalia in the absence of effective Somali ground operations that degrade the group’s havens regardless of who is overseeing its activity. The lack of flood-prevention efforts in central Somalia despite international funds for such projects is a microcosm of how government mismanagement will continue to present al Shabaab opportunities to undo the few military setbacks it suffers.

Afghanistan. The Operation Enduring Sentinel (OES) inspector general released the 2023 report for January–March 2023, which omits the threat Salafi-jihadi groups pose to US and Western interests in Afghanistan. The report’s purpose is to highlight Salafi-jihadi threats to US interests outside Afghanistan and the US homeland, but these groups also challenge Western interests in the country. The report rightly describes how these groups have benefited from the US withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021.

Water shortages are driving increased tensions between Iran and the Taliban. Reduced water flow from Afghanistan to Iran will undermine Iranian regime stability. Iran is unlikely to escalate the crisis and risk destabilizing Afghanistan.

Assessments:

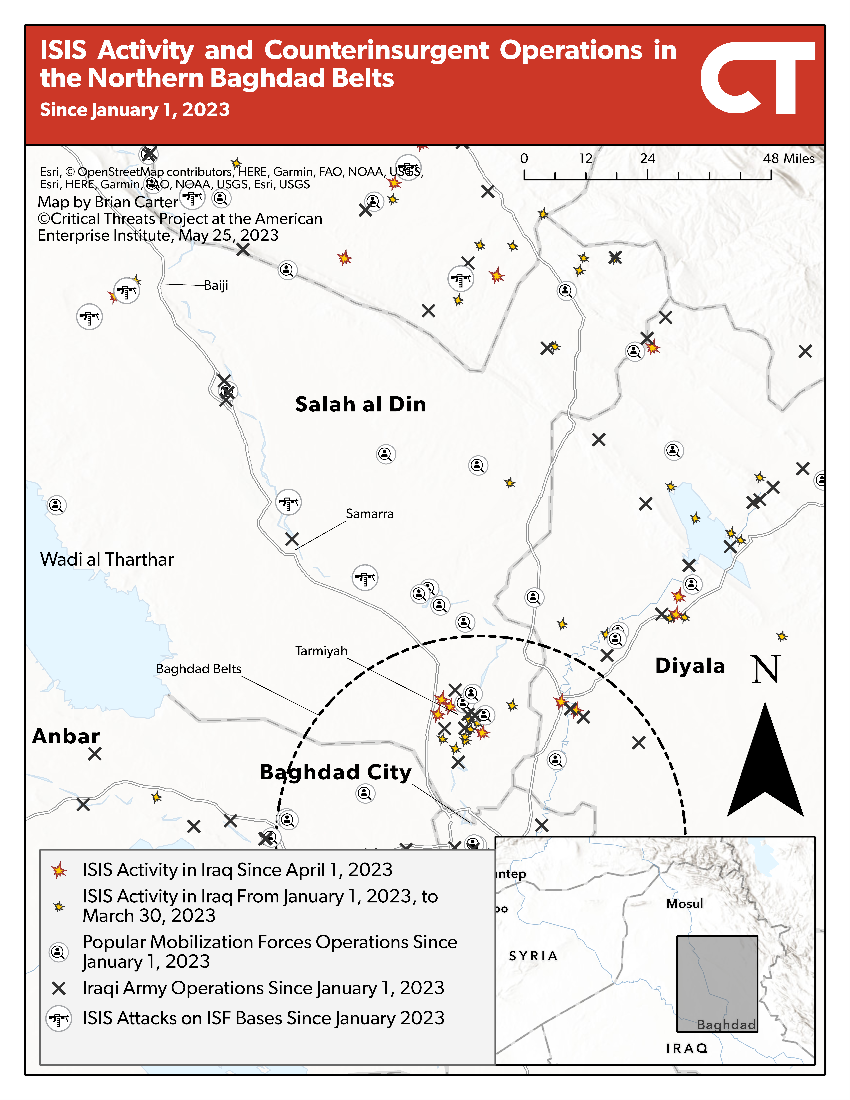

Figure 1. ISIS Activity and Counterinsurgent Operation in the Northern Baghdad Belts

Source: Brian Carter.

Iraq and Syria. ISIS is attempting to reconstitute itself and rebuild capabilities in the areas north and south of Baghdad, but it is likely to succeed only in the north, where local conditions are advantageous and ISIS can more adequately find support among the population and resupply its cells.[1] The areas around the city are a series of semi-urban and agricultural communities called the Baghdad Belts, which al Qaeda in Iraq and ISIS have historically used to launch attacks into the capital.[2] The northern Belt, including Tarmiyah, a key Sunni town, remains a permissive environment for ISIS’s influence due to the impact of Iranian-backed Shi’a militia calls for sectarian cleansing of Tarmiyah.[3]

ISIS has already begun setting conditions to take advantage of Iranian-backed Iraqi militia sectarian cleansing of Tarmiyah, writing that the militias seek to “extend [Iranian-backed militia] influence over [Tarmiyah], steal [Tarmiyah’s] wealth, and displace [Tarmiyah’s] people.”[4] Similar dynamics exist in the southern Baghdad Belts, where Iranian-backed Iraqi militias committed acts of sectarian cleansing in Jurf al Sakhr. ISIS cells in the southern Belts suffer from poor resourcing, bad operational security, and a reliance on a long, third-rate supply line through unpopulated and rough desert terrain.[5]

Iranian-backed militias and Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) frequently disrupt ISIS attacks in northern Babil province, where ISIS and its predecessor, al Qaeda in Iraq, had historic support zones.[6] The militias’ consistent disruption of attacks suggests a lack of ISIS operational security and safe areas from which the group can mount operations. CTP has not observed any ISIS support activities or efforts by ISIS to create support zones, which would be required for ISIS to reconstitute in the southern Belts.

ISIS cells in Tarmiyah are resourced and resilient, relative to ISIS cells south of Baghdad. ISIS is resourcing this effort using support zones in Wadi al Tharthar and the northern Anbar desert to support operations north of Baghdad. The group has mounted attacks aimed at enabling ISIS freedom of movement through this area by destroying thermal cameras and attacking Iraqi bases along the Tigris River.[7] ISIS is already slowly reconstituting itself in northern Baghdad after a series of ISF clearing operations in February and March 2023 forced a temporary ISIS pause in the area.[8] ISIS resumed operations targeting local armed actors in early May after a two-month pause by assassinating an alleged anti-ISIS spy, a local tribal militia leader, and a local Sunni militia patrol.[9] This trend illustrates Iraqi forces’ inability to interdict the ISIS supplies and cells that reenter the area after clearing operations to rebuild ISIS capabilities in the area.

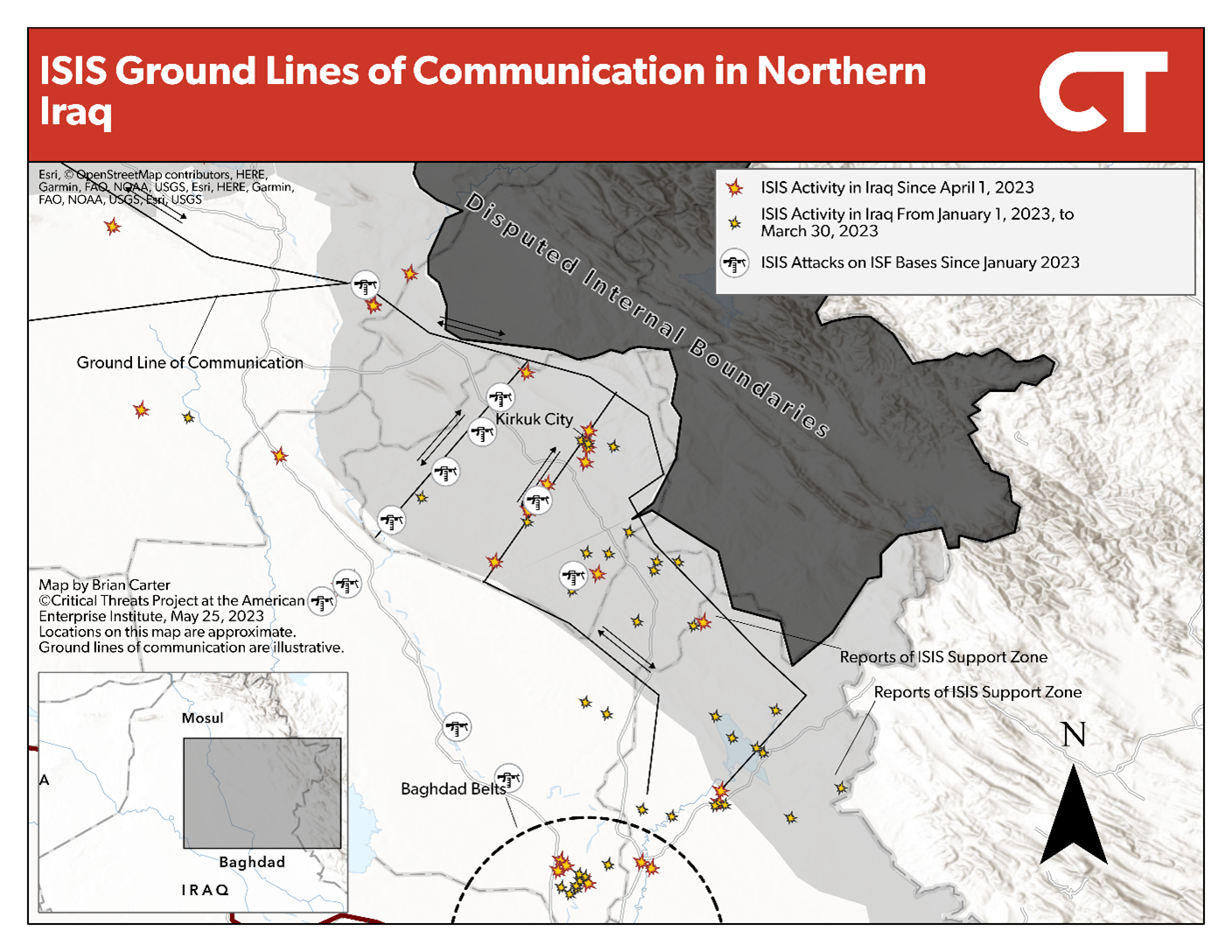

Figure 2. ISIS Ground Lines of Communication in Western Iraq

Source: Brian Carter.

The ISIS presence and ground lines of communication from Syrian regime-controlled south-central Syria through western Anbar province still represent a long-term threat to the southern Baghdad Belts and Iraq. ISIS is strongest in central Syria, and the Syrian regime is struggling to check ISIS’s ambition there. ISIS could use the unpopulated support areas it operates in western Anbar to gradually roll back ISF forces controlling more effective ground lines of communication to better resource ISIS cells if the ISF became distracted by a political crisis or other priorities. ISF operations typically dip during periods of unrest in Iraq.[10]

ISIS controls unpopulated territory in Wadi Doubayat in regime-controlled Syria, from which it can move forces deeper into Syria or across the border into Iraq. CTP has not observed Iraqi forces making a concerted effort to stop ISIS cross-border movement, and ISIS has targeted Iraqi outposts on the border to help enable the group’s movements.[11] ISIS also has agreements with Iran-backed militias to permit ISIS movements across the border.[12] Iraqi special operations forces raided a major ISIS camp in Wadi Houran in February, indicating a sizable ISIS presence in the Anbar deserts.[13]

Figure 3. ISIS Ground Lines of Communication in Northern Iraq

Source: Brian Carter.

Disputed Internal Boundaries. ISIS is maintaining ground lines of communication into the disputed internal boundaries (DIB), where the group has support zones that it will likely use to reinforce cells in Diyala province. ISIS fighters in April and May targeted thermal cameras at three Iraqi bases near the DIBs.[14] These cameras help Iraqi forces disrupt ISIS movement. ISIS will use the disruption to enable the group’s freedom of movement into the DIBs, where the group has limited support zones it can use to rest, resupply, and move forces to new areas, such as Diyala province.[15] Diyala has a diverse population, which has historically allowed ISIS and its predecessors to generate support by cultivating Sunni-Shi’a tension.[16]

Figure 4. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in the Middle East

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

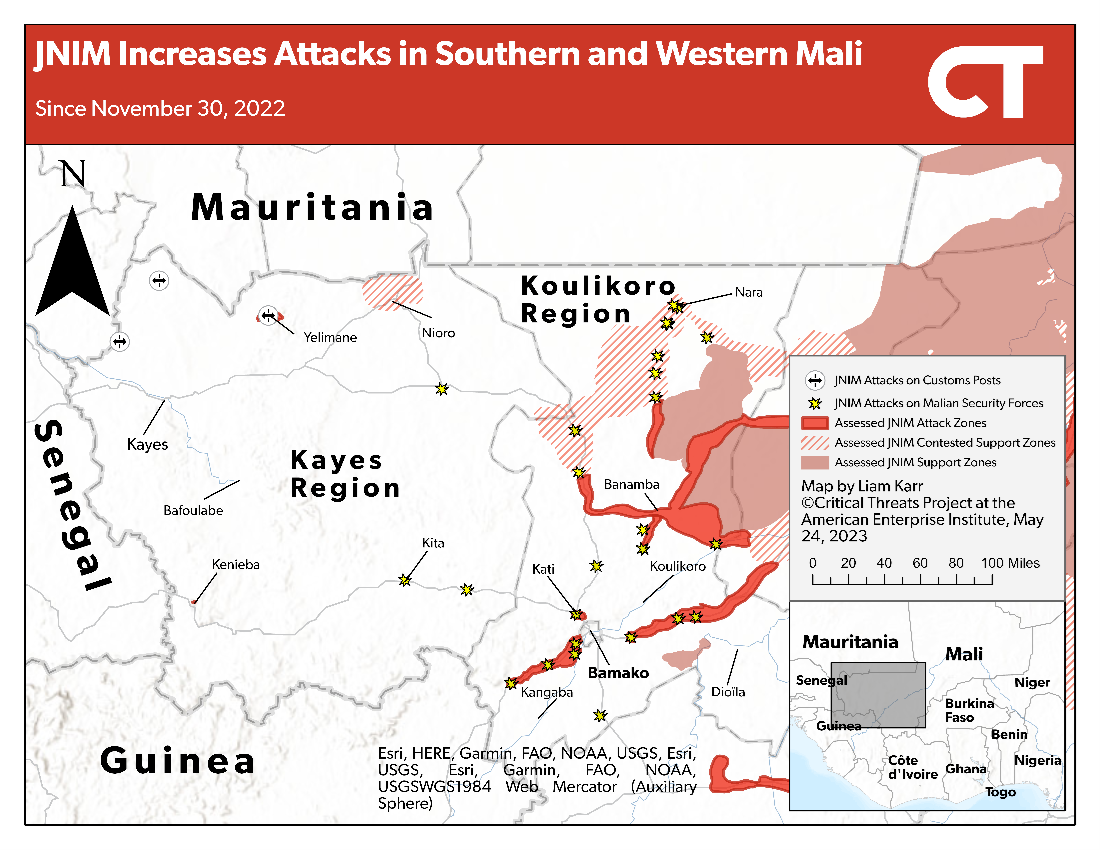

Mali. Al Qaeda–affiliated JNIM has increased its rate of attacks in western Mali since late 2022, likely to increase its revenue and degrade Malian lines of communication around the capital. JNIM has carried out three attacks in western Mali in May, equaling its yearly average since it became active in western Mali’s Kayes region in 2019. JNIM has conducted seven attacks in western Mali since December 2022. Three attacks in Kayes since November targeted customs posts close to the Malian-Mauritanian border.[17] JNIM loots money and weapons from the customs posts and could be coordinating the attacks with smugglers involved in the illicit gold, drug, arms, or human trafficking networks that use routes connecting western Mali to coastal West Africa.[18] Al Qaeda–linked militants have historically been part of a similar crime-terror nexus in northern Mali where they tax or provide paid protection along regional smuggling routes.[19] Four other JNIM attacks since November 2022 targeting Malian security forces near roads leading to Mali’s capital are part of an ongoing JNIM campaign likely aimed at degrading Malian lines of communication.[20]

JNIM may be trying to increase ties with the illicit networks in western Mali to strengthen its position in the area, which could create opportunities to spread its insurgency to coastal West Africa in the future. Al Qaeda–linked militants previously used illicit Sahelian networks to better integrate themselves into local communities, improving the organization’s ability to expand throughout the Sahel.[21] JNIM could seek to replicate a similar strategy in western Mali. Transnational crime networks in western Mali run into coastal West Africa, including Guinea, Mauritania, and Senegal.[22] Al Qaeda–linked militants use smuggling networks to move personnel and assets into North Africa but have not used smuggling routes to support operations in coastal West Africa.[23]

Al Qaeda and the Mauritanian government may have a nonaggression pact that would decrease the likelihood of JNIM expansion into Mauritania. Internal al Qaeda documents show that its regional leadership discussed a deal with the Mauritanian government in 2010, and al Qaeda–linked militants have not attacked in Mauritania since 2011.[24] However, al Qaeda threatened Mauritania in 2018, and Mauritania is leading efforts to revitalize regional counterterrorism cooperation after Mali withdrew from the regional counterterrorism bloc in May 2022.[25] There are also many Mauritanians in JNIM that could return to Mauritania if al Qaeda gives more priority to the country.[26] Four al Qaeda–linked jihadists briefly escaped from prison and killed two guards in the Mauritanian capital in March 2023, underscoring that al Qaeda’s regional network remains a threat to Mauritania.[27]

Figure 5. JNIM Increases Attacks in Southern and Western Mali

Source: Liam Karr.

Somalia. Somali-US drone strikes targeting al Shabaab leadership may temporarily weaken the group’s capabilities without disrupting al Shabaab’s regional threat. The Somali Federal Government (SFG) and US Africa Command conducted a drone strike that wounded al Shabaab’s external operations head Moalim Osman in southern Somalia on May 22.[28] Osman oversees foreign fighter recruitment and helps plan attacks in Kenya and Ethiopia.[29] Al Shabaab is a networked, decentralized organization that has no single point of failure and will continue to recruit from ethnically Somali areas of Ethiopia and Kenya using local grievances and social networks regardless of who is overseeing the operations.[30]

The al Shabaab network will continue organizing its regional insurgency from southern Somalia in the absence of effective SFG-led ground operations that degrade its havens. The group governs significant portions of southern Somalia, where it levies taxes and has military infrastructure.[31] The SFG has continually delayed a planned offensive in southern Somalia due to seasonal flooding and a lack of local and international support that it says will eventually retake these havens.[32] CTP has previously assessed that this potential offensive is unlikely to clear these al Shabaab–controlled areas due to strong al Shabaab resistance and that it will be almost impossible for the SFG to hold any gains over the following years due to a lack of adequate holding forces.[33]

Killing the al Shabaab leadership will also have unintended consequences on internal al Shabaab divisions. The May 22 strike could have impacted the balance of a rumored split between al Shabaab’s Somali fighters and foreign fighters due to Osman’s large role in foreign fighter recruitment.[34] This factional divide is increasingly important given the multiyear rumors that the al Shabaab emir is in poor health and was briefly incapacitated in 2020.[35] The strongest faction will chart the group’s future and dictate who becomes the next emir.

Central Somalia Floods. Recent floods in central Somalia underscore that addressing government mismanagement will be key to preventing al Shabaab from returning to newly liberated villages in central Somalia. Somali forces liberated dozens of villages across central Somalia in 2022 and 2023, including numerous settlements along the Shabelle River Valley, where floods displaced at least 245,000 people in May.[36] Climate change is likely making these floods more common, as flooding on a similar scale happened in 2020.[37] Italy donated $6 million to fund state government–led flood-prevention efforts after the 2020 floods, but the state government never implemented any projects.[38]

The central Somalia offensive has improved the security situation to the point where implementing climate resilient development is more possible, but the local and federal government will need to use international funding effectively. Mismanaged disasters will likely increase apathy or frustration with the government and prompt mass migration that al Shabaab can exploit to reestablish itself in the newly liberated areas.[39]

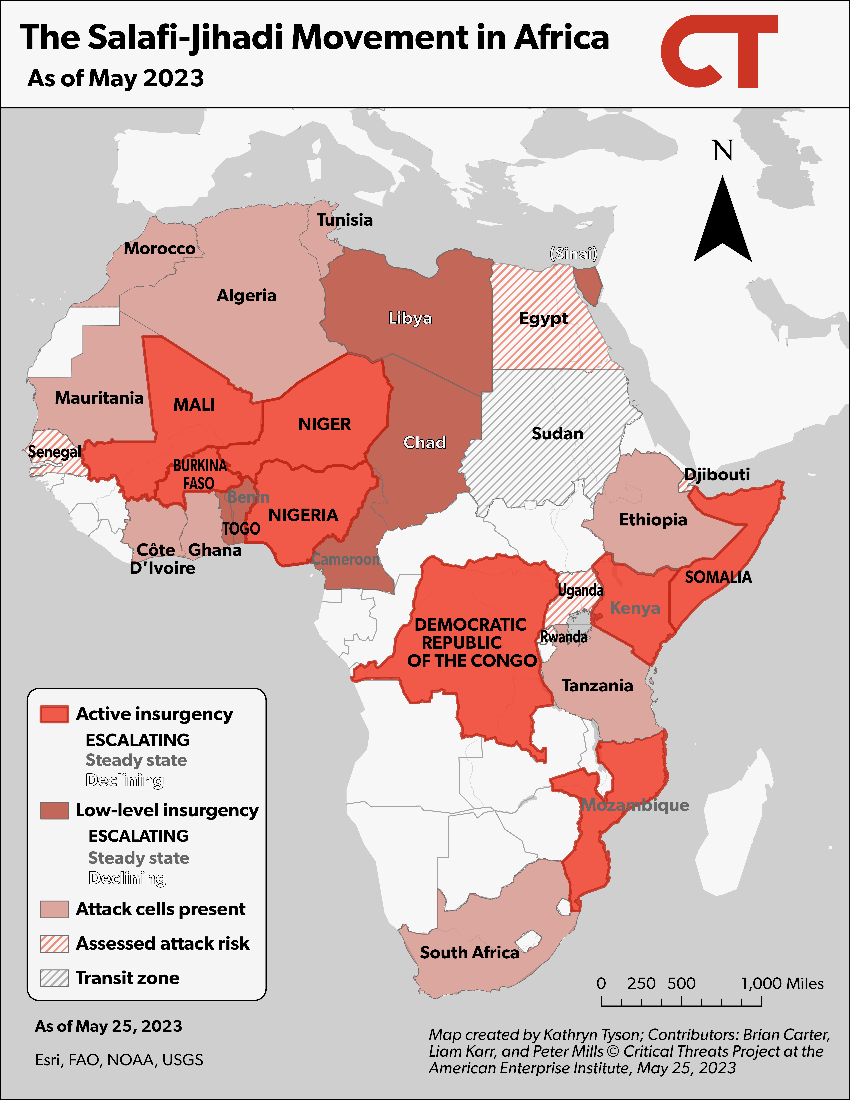

Figure 6. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

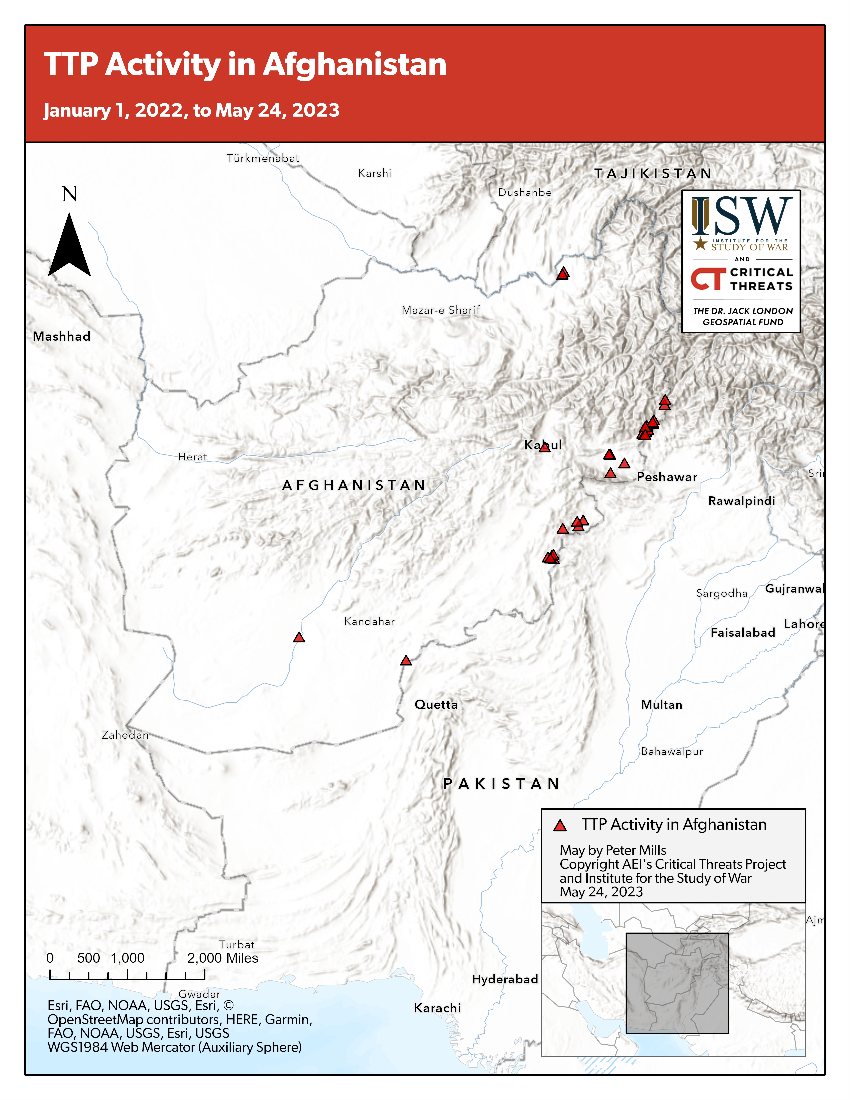

Figure 7. TTP Activity in Afghanistan

Source: Peter Mills.

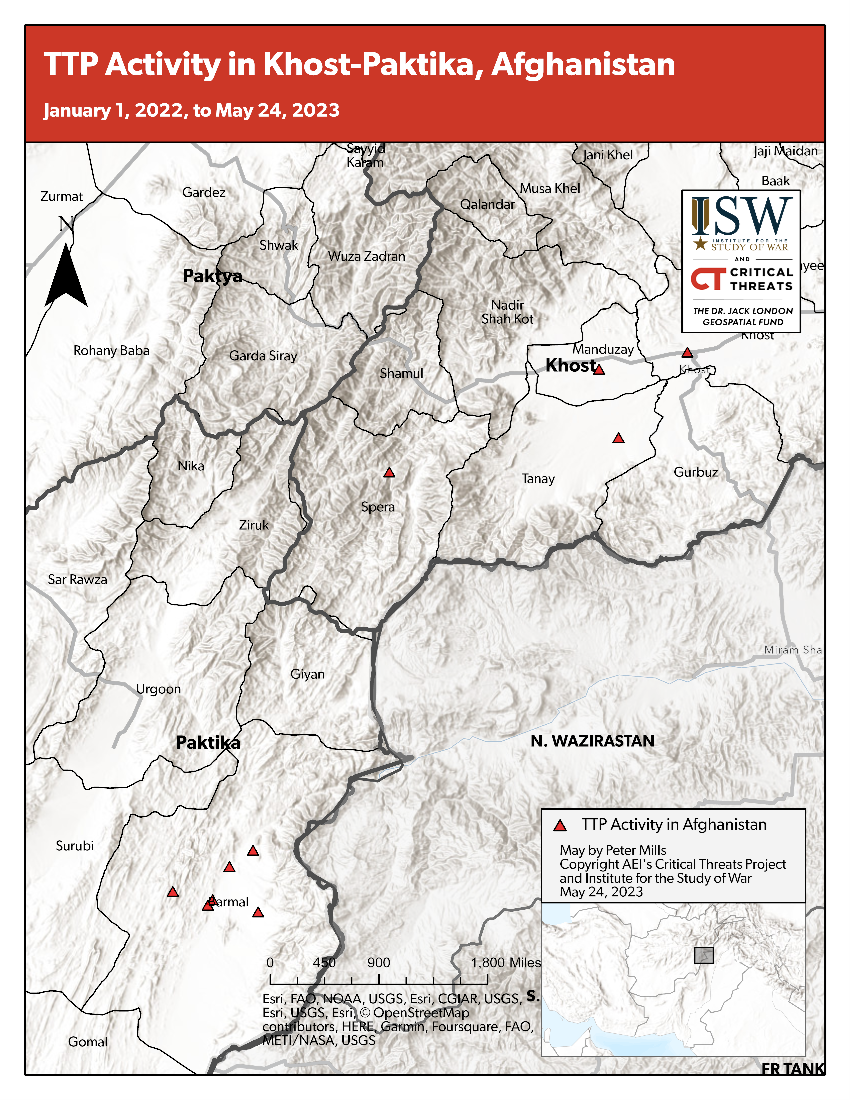

Figure 8. TTP Activity in Khost-Paktika, Afghanistan

Source: Peter Mills.

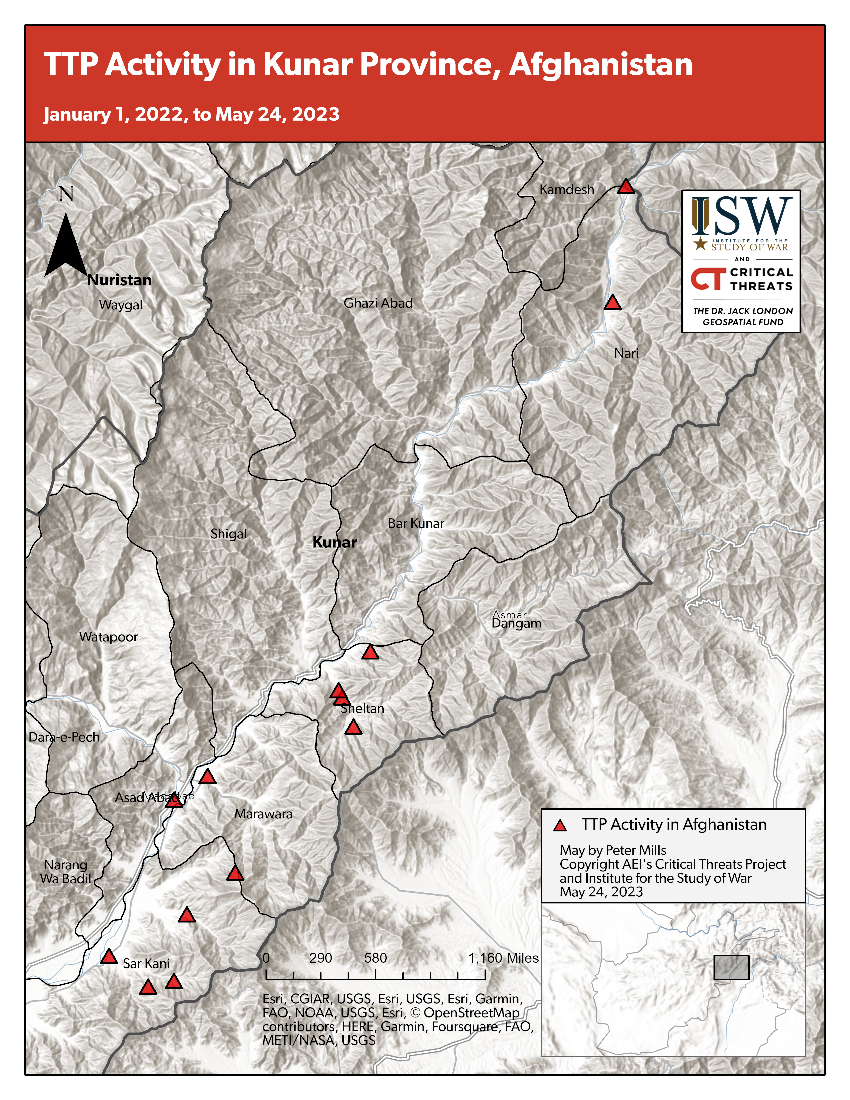

Figure 9. TTP Activity in Kunar Province, Afghanistan

Source: Peter Mills.

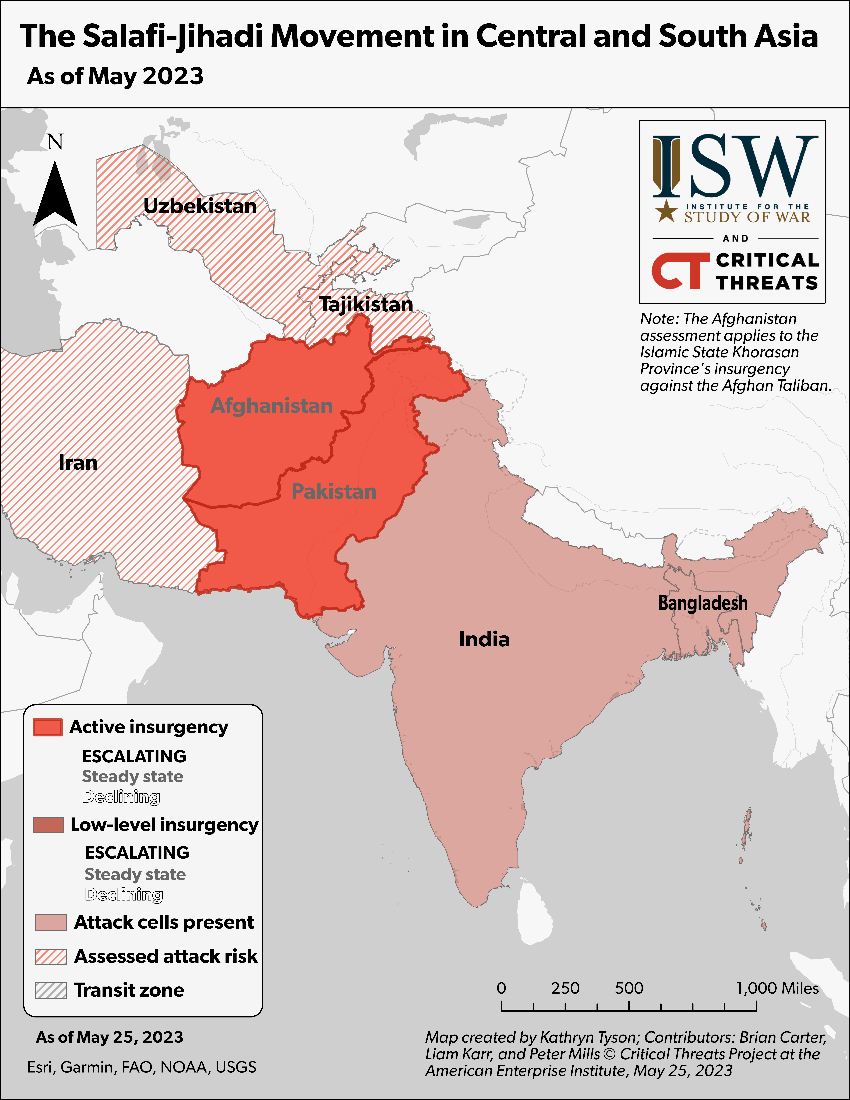

Afghanistan. The OES inspector general released the 2023 first quarter report for January–March 2023, which omits the threat Salafi-jihadi groups pose to US and Western interests in Afghanistan.[40] The purpose of the report is to highlight Salafi-jihadi threats to US interests outside of Afghanistan and the US homeland, but these groups also challenge US and Western interests in the country.

The Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) have hindered US diplomatic engagement in Afghanistan. US embassies limited travel by diplomatic staff in December 2022 and February 2023 due to TTP and ISKP threats and attacks.[41] The previous US embassy restriction on staff in Pakistan due to a terror threat was in 2019. [Read Kathryn Tyson and Katie Zimmerman’s latest piece on Salafi-jihadi threats to US embassies.[42]]

The TTP and ISKP also threaten broader Western interests in Pakistan. Dozens of TTP militants attacked security guards and damaged a Hungarian-owned oil site in northwestern Pakistan on May 23.[43] The UN closed an office in Islamabad due to an ISKP threat after protestors burned a Quran in Sweden in February 2023.[44] The Swedish embassy in Islamabad closed indefinitely in April due to security concerns likely related to ISKP threats over the Quran incident.[45]

The report rightly describes how ISKP and the TTP have grown stronger in the past year. Both groups have benefited from the August 2021 US withdrawal from Afghanistan because the Afghan Taliban has been unable to effectively combat them.

The Taliban lacks the intelligence capabilities to preemptively disrupt ISKP attacks. The Taliban have killed high-level ISKP leaders in 2023, but the killings fail to address ISKP supporters within the Taliban government and intelligence services.[46] The report also describes Taliban counter-ISKP operations as using “brute force,” which marginalizes civilians and increases support for anti-Taliban groups, including ISKP.[47] ISKP seeks to exploit weak security under the Taliban to attack US and Western interests abroad, and could carry out such an attack within the next six months, according to the report.

The Taliban takeover in Afghanistan has also benefited the TTP in Pakistan. The OES report said that the majority of TTP fighters reside in Afghanistan. The Taliban continues to tolerate the TTP’s presence in the country, meaning the TTP threat will likely worsen.[48] The Taliban has repeatedly denied that the TTP operates out of Afghanistan, despite the killings of senior TTP leaders in the country.[49]

Afghanistan-Iran. A worsening water dispute between Iran and the Taliban may exacerbate water shortages that undermine regime stability in Iran. Both Iran and Afghanistan are experiencing drought, which is driving a zero-sum competition for shared water resources.[50] Senior Taliban leaders denied Iran’s request for more water and claimed they cannot release any more water due to drought.[51] The Taliban is attempting to increase the amount of water available to local farmers by building a new dam in western Afghanistan.[52] Water shortages are one of the drivers of anti-regime protests in Iran.[53]

Iran is unlikely to escalate or attempt to destabilize Afghanistan because of the tensions over water supplies. A destabilized Afghanistan would risk an influx of Afghan refugees and drugs into Iran. Iran and the Taliban’s deputy chiefs of staff for the armed forces met to discuss border issues on May 20, which indicates ongoing military cooperation.[54] Iranian state media framed these talks as delivering an unspecified warning to the Taliban.[55]

Taliban Internal Politics. The Taliban supreme leader appointed a new Taliban prime minister to manage the internal Taliban government tensions with the Haqqani Network, which is unlikely to change Taliban policies toward the TTP. The Taliban supreme leader replaced former Taliban Prime Minister Hassan Akhund with Abdul Kabir on May 16.[56] Akhund had health problems throughout 2022 and had previously tried to resign as prime minister.[57] Kabir is from the Zadran Pashtun tribe from Paktia Province—sharing local and tribal ties with the Haqqani Network leadership. The Taliban supreme leader may use Kabir to divide the Haqqani Network’s Zadran support base and manage tensions between the supreme leader and the Haqqani Network over the distribution of power within the Taliban government.[58] Both the Haqqani Network and the Taliban supreme leader have offered rhetorical support for the TTP.[59]

Figure 10. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Central and South Asia

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

[1] https://www.alahednews dot com.lb/fastnewsdetails.php?fstid=192402; https://zagrosnews dot net/ar/news/40676; https://www.ina dot iq/181009--.html; https://shafaq dot com/ar/%D8%A3%D9%85%D9%80%D9%86/%D8%A7%D9%84-%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%82%D9%8A-%D9%8A%D9%83%D8%B4%D9%81-%D9%87%D9%88%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D9%82%D8%AA%D9%84%D9%89-%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%B9%D8%B4-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%B9%D9%85%D9%84%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B7%D8%A7%D8%B1%D9%85%D9%8A%D8%A9

[2] https://www.understandingwar.org/region/baghdad-belts#:~:text=The%20Baghdad%20belts%20are%20residential,to%20the%20rest%20of%20Iraq

[3] https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/jurf-al-sakhar-model-militias-debate-how-carve-out-new-enclave-north-baghdad

[4] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/iran-update-april-27-2023; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-february-22-2023

[5] https://www.newarab dot com/news/iraqi-militias-transformed-town-secret-prison-says-mp; https://diyaruna dot com/en_GB/articles/cnmi_di/features/2020/02/17/feature-01

[6] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/iraq-update-34-data-suggests-rise-violence-along-historic-fault-lines

[7] ISIS claims available on request.

[8] https://www.alahednews dot com.lb/fastnewsdetails.php?fstid=192402; https://zagrosnews dot net/ar/news/40676; https://www.ina dot iq/181009--.html; https://shafaq dot com/ar/%D8%A3%D9%85%D9%80%D9%86/%D8%A7%D9%84-%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%82%D9%8A-%D9%8A%D9%83%D8%B4%D9%81-%D9%87%D9%88%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D9%82%D8%AA%D9%84%D9%89-%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%B9%D8%B4-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%B9%D9%85%D9%84%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B7%D8%A7%D8%B1%D9%85%D9%8A%D8%A9

[9] ISIS claims available on request.

[10] https://media.defense.gov/2022/Nov/21/2003119338/-1/-1/1/LEAD%20INSPECTOR%20GENERAL%20FOR%20OIR.PDF

[11] Author’s research; sources and ISIS claims available on request.

[12] https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2022/12/syrian-rebels-kill-caliph-attacks-continue-iraq-syria

[13] https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2023/03/500-fighters-still-active-iraq-military#ixzz7vmFREkYf

[14] Author’s research; ISIS claims available on request.

[15] Author’s research.

[16] https://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/reports/Security%20Diyala%20-%20Iraq%20Report%2010.pdf; https://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/Lewis-Diyala.pdf

[17] http://malijet dot com/actualite-politique-au-mali/flash-info/275019-region-de-kayes-le-camp-militaire-et-la-douane-de-yelimane-attaq.html; https://twitter.com/ocisse691/status/1658076898197487616?s=20; https://twitter.com/Wamaps_news/status/1660620772212105216?s=20

[18] https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/west-africas-cocaine-corridor; https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Human-smuggling-and-trafficking-ecosystems-MALI.pdf; https://issafrica.org/iss-today/how-western-mali-could-become-a-gold-mine-for-terrorists; https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/tocta_sahel/TOCTA_Sahel_firearms_2023.pdf

[19] https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/AQIMs-Imperial-Playbook.pdf; https://africacenter.org/publication/puzzle-jnim-militant-islamist-groups-sahel; https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/jnim-burkina-faso

[20] https://twitter.com/SimNasr/status/1600758655900876800; https://www.barrons.com/articles/policeman-killed-in-jihadist-torn-mali-01673278808; https://twitter.com/ocisse691/status/1651218022206406668?t=WehSbEp_dATHN8DeH5mFbQ&s=19; https://twitter.com/ocisse691/status/1656233886748164096?s=20; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-april-5-2023

[21] https://ctc.westpoint.edu/aqims-imperial-playbook-understanding-al-qaida-in-the-islamic-maghrebs-expansion-into-west-africa

[22] https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/west-africas-cocaine-corridor; https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-report/senegal; https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Human-smuggling-and-trafficking-ecosystems-MALI.pdf; https://www.unodc.org/res/som/docs/Observatory_StoryMap_3_NorthWestAfrica.pdf; https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/maritime-irregular-migration-canary-islands

[23] https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA/Display/Article/2425320/lassoing-the-haboob-countering-jamaat-nasr-al-islam-wal-muslimin-in-mali-part-i; https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/tocta_sahel/TOCTA_Sahel_som_2023.pdf

[24] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-binladen-mauritania-idUSKCN0W356G; https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20230306-four-jihadists-escape-in-deadly-prison-break-in-mauritania; https://ctc.westpoint.edu/renewed-jihadi-terror-threat-mauritania

[25] https://www.africaintelligence.com/west-africa/2023/05/22/nouakchott-s-plans-to-revive-g5-sahel,109976362-art; https://www.africaintelligence.com/west-africa/2023/03/09/ghazouani-strives-to-get-bamako-back-into-g5-sahel,109921827-art; https://www.africaintelligence.com/west-africa/2023/03/09/ghazo; https://usun.usmission.gov/remarks-at-a-un-security-council-briefing-on-the-g5-sahel-3; https://usun.usmission.gov/remarks-at-a-un-security-council-briefing-on-the-g5-sahel-3https://usun.usmission.gov/remarks-at-a-un-security-council-briefing-on-the-g5-sahel-3

[26] https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20230306-four-jihadists-escape-in-deadly-prison-break-in-mauritania; https://ctc.westpoint.edu/renewed-jihadi-terror-threat-mauritania

[27] https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20230306-four-jihadists-escape-in-deadly-prison-break-in-mauritania

[30] See paragraph 4-103 in https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/fm3_24.pdf; https://library.au.int/how-do-individuals-join-al-shabaab-ethnographic-insight-recruitment-models-al-shabaab-network-kenya; https://ctc.westpoint.edu/kenyas-muslim-youth-center-and-al-shababs-east-african-recruitment

[31] https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/al-shabaab-tax; https://hiraalinstitute.so/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Al-Shabaabs-Arsenal-From-Taxes-to-Terror-Web.pdf

[33] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-march-8-2023; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-may-10-2023#Somalia20230510

[34] https://garoweonline dot com/en/news/somalia/al-shabab-infighting-escalates-attack-on-senior-foreign-leader-s-house-in-jilib-city

[35] https://jamestown.org/program/al-shabaab-faces-leadership-battle-as-speculation-over-emirs-health-mounts; https://www.garoweonline dot com/index.php/en/news/somalia/al-shabaab-leader-hands-over-to-deputy-amid-ill-health-speculations; https://extremism.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs5746/files/Al-Shabaab-IMEP_Bacon_March-2022.pdf

[36] https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/somalia/b187-sustaining-gains-somalias-offensive-against-al-shabaab; https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/may/17/city-underwater-quarter-of-million-somalians-flee-homes-floods; https://www.cnn.com/2023/05/18/africa/somalia-flooding-displaced-intl/index.html; https://apnews.com/article/somalia-flooding-displaced-0b884e92dee5246da716ad9d00886ade

[38] https://sooha dot org/en/2020/08/10/italy-pledges-6-mln-for-flood-prevention-project-in-hirshabelle; https://www.ftlsomalia dot com/italy-has-approved-6m-for-flood-prevention-says-hirshabelle-president; https://twitter.com/DhaqaneDK/status/1657037034597367813?s=20

[39] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/may/17/city-underwater-quarter-of-million-somalians-flee-homes-floods

[40] https://www.dodig.mil/In-the-Spotlight/Article/3396442/lead-inspector-general-for-operation-enduring-sentinel-january-1-2023-march-31

[41] https://crisis24.garda.com/alerts/2022/12/pakistan-us-embassy-prohibits-staff-from-visiting-mariott-hotel-in-islamabad-as-of-dec-25; https://pk.usembassy.gov/security-alert-terrorist-attack-in-peshawar

[43] https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/islamist-militants-kill-six-gas-oil-extraction-plant-pakistan-2023-05-23

[44] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jan/21/turkey-condemns-burning-of-quran-during-far-right-protest-in-sweden; https://twitter.com/nviTweets/status/1623736779944886272

[45] https://crisis24.garda.com/alerts/2023/04/pakistan-the-swedish-embassy-in-islamabad-closed-indefinitely-as-of-april-11

[46] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-march-1-2023; https://twitter.com/bsarwary/status/1630657787150712837

[49] https://www.voanews.com/a/taliban-tell-pakistan-not-to-blame-afghanistan-for-mosque-bombing-/6943345.html; https://www.rferl.org/a/pakistan-taliban-commanders-killed-abdul-wali/31977631.html

[50] https://thediplomat.com/2022/02/afghanistan-iran-disquiet-over-the-helmand-river; https://8am.media/eng/securitization-of-the-water-issue-between-afghanistan-and-iran

[51] https://twitter.com/AOP_IEA/status/1659250537793978392; https://twitter.com/IeaOffice/status/1659108148328685569; https://twitter.com/Mukhtarwafayee/status/1660638766682234880

[52] https://amu dot tv/en/49166; https://twitter.com/MJalal0093/status/1659863748926898176

[53] https://time.com/6239669/iran-protests-water-crisis; https://www.rferl.org/a/iran-prtests-water-cuts/32002848.html

[55] https://www dot independentpersian dot com/node/330251

[56] https://twitter.com/TOLOnews/status/1658529606897647618; https://twitter.com/SamiYousafzaii/status/1658334691789774849

[57] https://8am dot media/eng/taliban-prime-minister-suffers-from-congestive-heart-failure-disease

[58] https://www dot thenationalnews dot com/world/2023/05/22/talibans-cabinet-reshuffle-an-attempt-to-consolidate-power-analysts-say; https://8am dot media/eng/mawlawi-abdul-kabirs-roles-in-afghanistans-political-theater